In his new book, The Human City, Joel Kotkin looks at the ways cities succeed or fail in terms of how their residents are best served. Here’s a tour of some past models.

Throughout history, urban areas have taken on many functions, which have often changed over time. Today, this trend continues as technology, globalization, and information technology both undermine and transform the nature of urban life. Developing a new urban paradigm requires, first and foremost, integrating the traditional roles of cities—religious, political, economic—with the new realities and possibilities of the age. Most importantly, we need to see how we can preserve the best, and most critical, aspects of urbanism. Cities should not be made to serve some ideological or aesthetic principle, but they should make life better for the vast majority of citizens.

In building a new approach to urbanism, I propose starting at the ground level. “Everyday life,” observed the French historian Fernand Braudel, “consists of the little things one hardly notices in time and space.” Braudel’s work focused on people who lived largely mundane lives, worried about feeding and housing their families, and concerned with their place in local society. Towns may differ in their form, noted Braudel, but ultimately, they all “speak the same basic language” that has persisted throughout history.

Contemporary urban students can adopt Braudel’s approach to the modern day by focusing on how people live every day and understanding the pragmatic choices they make that determine where and how they live. By focusing on these mundane aspects of life, particularly those of families and middle-class households, we can move beyond the dominant contemporary narrative about cities, which concentrates mostly on the young “creative” population and the global wealthy. This is not a break with the urban tradition but a validation of older and more venerable ideals of what city life should be about. Cities, in a word, are about people, and to survive as sustainable entities they need to focus on helping residents achieve the material and spiritual rewards that have come with urban life throughout history.

Cities have thrived most when they have attracted newcomers hoping to find better conditions for themselves and their families and when they have improved conditions for already settled residents. Critical here are not only schools, roads, and basic forms of transport, which depend on the government, but also a host of other benefits—special events, sports leagues, church festivals—that can be experienced at the neighborhood, community, and family levels.

This urban terroir—the soil upon which cities and communities thrive—has far less to do with actions taken from above than is commonly assumed by students of urban life. Instead, it is part of what New York folklorist Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett calls, “everyday urbanism,” which “take[s] shape outside planning, design, zoning, regulation, and covenants, if not in spite of them.”

This divergence in perspective, notes Los Angeles architect John Kaliski, stems in part from the desire of planners and architects to construct “the conceptually pure notion of what a city is or should be.” The search for a planned utopia, he says, also ignores the “situational rhythm” that fits each specific place and fits the demand of consumers in the marketplace. No surprise then that grand ideas, epitomized by soaring towers, often prove less successful than those more pragmatic, market-oriented efforts of, say, Victor Gruen to recreate the plaza and urban streetscape within the framework of modern-day suburbia.

So rather than just focusing on grand narratives about how to transform the metropolis and its denizens, we need to pay more attention to what people actually do, what they prefer, and those things to which they can reasonably aspire. The history of successful cities reveals that, although their functions change, cities have to achieve two things: a better way of life for their residents and a degree of transcendence critical to their identities.

In addressing the wider issues faced by urban residents, we need to also draw on older urban traditions that have emerged over the last three millennia. Jane Jacobs’s idealistic notions of cities, however outdated, contain meaningful insights—about the importance of diverse, child-friendly, dense city neighborhoods, for example. By exploring the deeper veins of urbanity—spiritual, political, economic—we can begin to hone our efforts to improve and develop our cities so that they are more pleasant, and particularly more accommodating, for people as they go through the various stages of life.

THE CITY OF GOD

Early cities rested largely on urban studies scholar Robert Park’s notion of cities as “a state of mind [and] a body of customs and traditions.” The earliest urban residents built their cities with the idea that they were part of something larger than themselves, connected not only to their own traditions but to divinity itself. Great ancient cities were almost always spiritual centers, and as the great urban historian Lewis Mumford noted, religion provided a critical unifying principle for the city and its civic identity:

“Behind the wall of the city life rested on a common foundation, set as deep as the universe itself: the city was nothing less than the home of a powerful god. The architectural and sculptural symbols that made this fact visible lifted the city far above the village or country town … To be a resident of the city was to have a place in man’s true home, the great cosmos itself.”

In the decidedly non-urban world of early times, the city’s spiritual power helped define a place and animate its residents with a sense of common identity. This attachment still remains notable in cities such as Jerusalem and Mecca. Jerusalem, shortly after its conquest by the Hebrews, began as a powerful and strategic fortress but evolved, with the building of David’s temple, into the “holy city,” a status it has maintained for three major religions to this day. “Jerusalem,” notes one historian, “had no natural industries but holiness.” Even today, as political scientist Avner de-Shalit suggests, “Many Jerusalemites are proud of living in a city where spirituality is more important than materialism and wealth.”

Many other cities, perhaps less cherished for holiness, have served as repositories for essential cultural ideas and ethnic memories—a role that still exists today. The special appeal of cities such as Kyoto, Beijing, Rome, Paris, and Mexico City stems in part from their being built on foundations of earlier civilizations, even those like the Aztecs’ ancient Tenochtitlan, whose religious structures were systematically destroyed and replaced by those of their Catholic conquerors.

In this sense, great cities—even as they expanded via armed conquest and the control of an ever-expanding hinterland—cultivated the notion of their distinct connection to eternity. In many cases, from Babylon to China, kingship was “lowered from heaven,” thus connect- ing early theologically-based urbanism to the notion of power. In Babylon, for example, all property was theologically under the sovereignty of god, for whom the human ruler served as “steward.”

Today, urban thinkers barely reflect on such considerations, particularly those concerning religion or the role of the sacred, which has been historically critical to creating the moral order that sustains cities. Indeed, some have argued that higher degrees of secularism are essential to the creation of a more advanced and progressive society.

But one does not have to view traditional religious underpinnings as the only way to nurture “sacred space.” Today, notes urban analyst Aaron Renn, this sense of identity often extends to secular places like Times Square in New York or the Indiana War Memorial in Indianapolis; it could be the Eiffel Tower in Paris, Trafalgar Square in London, or the mountains visible from the great cities of the American West: Los Angeles, Denver, Phoenix, San Francisco, Seattle, and Portland. Cities in continental Europe have been defined by their countless squares, such as Place de la République in Paris, Piazza del Duomo in Milan, and the Grote Markt in Brussels, as well as the manicured parks in Australian and Chinese city centers, such as Sydney’s Hyde Park and Beijing’s Beihai Park.

THE IMPERIAL CITY

equivalents, drove city life to aspire to higher ideals, the notion of power—notably that of the supreme and absolute monarch—was critical in the development of the first giant cities. The imperial city not only expressed the egotism of rulers and the ambition of builders but also reflected a critical notion of the city as being deeply connected to a sense of transcendence over other, less exalted places. Peter the Great, for example, believed that in Saint Petersburg, he was building something divine on earth. “Truly,” he commented, “we live here in heaven.”

Saint Petersburg epitomized another critical role of cities: to function as windows, or gateways, to a wider world. The late British philosopher Stephen Toulmin suggested that, in the merger of “the polis” with “cosmos,” the city takes the lead in ordering nature and society alike. This sense of possibility, of creating better and newer ways of life, has long been an important function of cities.

In the imperial city, God was hardly banished; instead, the focus turned more toward mastery of the human condition. Imperial Athens, for example, sought to export not so much religion but rather a more generalized culture that reflected the Greek way of life, such as its political forms, art, and fashion. The Greek city-states also exported such prosaic practices as the use of olive oil to both trading partners and conquered territories. Here we first see a distinct urban culture on the march, defiant about its superiority over the countryside. As Socrates is said to have remarked, “The country places and trees won’t teach me anything, and the people in the city do.”

Athens’s successor, Rome, was built on the idea of the state—the res publica, which Romans perceived as being inherently superior and deserving of global preeminence. There was clearly a spiritual element here. Ancient Roman historian Titus Livius Patavinus, known today as Livy, spoke of how the Gods “inhabit[ed]” the city—but the primary exports of Rome were its power, systems of urbanization, and legal system.

With Rome, we also see the emergence, for the first time, of a city with a population of 1 million or more, bringing with it the great challenges still faced by large cities today. Most Romans were descended from slaves and many, like their contemporaries in today’s megacities, lived in crowded, unsanitary, and dangerous conditions—and often paid exorbitant rents. As the empire expanded, many of the old plebeian class were driven into poverty as they were replaced with slave labor. As we’ll discuss later, this misery amid all the splendor and elegance associated with the imperial elite has remained a common reality in great cities throughout much of urban history.

This “princely city” dominated by political power, as German sociologist Max Weber noted, produced what Weber identified as “the consumer city,” a place driven by the wealth of individuals connected to the political or clerical regime. These areas were dominated by privileged rentiers, and the large servile class, free or not, was employed to tend to their needs.

As we’ll see, this earliest consumer city—tied to the presence of the court and courtiers—was a precursor of the luxury urban cores of today. As Rome declined, this role was assumed by the new capital, Byzantium (later Constantinople), which emerged as the world’s largest city, reaching its peak population in 500 AD. The city’s power was based largely on its serving as center of what remained of the empire as well as the headquarters of the Orthodox Church. As a result, it created a large consuming class of priests, bureaucrats, and soldiers who enjoyed its many pleasures.

Over the next two millennia, similar patterns could be seen in Beijing, Damascus, Tokyo, Paris, Vienna, and Cairo, all of which grew largely as the result of imperial expansion and centralized government, with its attendant need for bureaucrats, scribes, and religious leaders. For example, Vienna, a city not noted for its commercial prowess, grew fivefold between 1600 and 1800, outpacing the other cities of central Europe. Such centralization of power often led to ambitious building projects, not only in Vienna but also in Imperial Paris and later in the capital of a rising Prussian and then German empire, Berlin.

In some cases, such as in Washington, D.C., political power, rather than the patronage of the rich, transformed a once sleepy metropolis. As late as 1990, the British geographer Emrys Jones considered it “doubtful” that Washington could ever be considered among the world’s leading cities. Yet, as the U.S. federal government grew in size and complexity, so, too, did the area. Washington is now very much a global metropolis, with one of the strongest economies in North America and a growing immigrant population.

Some of today’s large Asian cities—Beijing, Seoul, and Tokyo— also derive their importance, in part, from serving as centers of political power. In the case of Beijing, this focus on centralization remained intact after the Communist takeover in 1949, with party cadres playing the leading role and turning the capital into the country’s dominant city over the old commercial capital of Shanghai. In all of these capitals, the central governments exercised inordinate influence over both the economy and society.

THE PRODUCER CITY

Most major cities today depend largely on their prowess as economic units. This development, as Karl Marx suggested, reflected the replacement of the wealthy land-owning aristocracy with the merchant and money-lending classes, the earliest capitalists. In contrast to the aforementioned consumer city dominated by princes, Weber described these as “producer cities.” Venice was an early example. This Italian city-state pioneered the use of industrial districts built largely to meet export demand. Venice was primarily a mercantile city, dependent on the export of goods and services to the rest of the world for its livelihood.

Arguably, the most evolved of the early producer cities emerged in the Netherlands, a place that limited both imperial and ecclesiastical power. The Netherlands crafted a great urban legacy that, in its initial phases, involved rising living standards and remarkable social mobility. These trends led the Dutch to be widely denounced as avaricious people who valued physical possessions more than spiritual or cultural values.

Yet this urban culture, as English historian Simon Schama noted, offered a high quality of life to its middle and working classes and even served its poorest class reasonably well. These Dutch cities—home to over 40 percent of Netherlanders—not only remained wealthier than those of other European countries but also managed to improve such things as hygiene and provide a better environment for children and families. They also accommodated many outsiders, a pattern still seen today, particularly in key global cities. Many outsiders, such as Jews and Huguenots, flocked to Dutch cities, in large part for both economic opportunities and greater religious freedom. The religious and ethnic heterogeneity of the Dutch cities also encouraged independent thinking and the mixing of cultures; in the second half of the 17th century, more than one-third of Amsterdam’s new citizens came from outside the Netherlands. This openness was critical to developing innovative approaches to the arts and philosophy, such as the groundbreaking writings of Baruch Spinoza.

The producer city provided the template for a city that served its commercial interests and nurtured a middle class, rather than being built around the needs of kings, aristocrats, prelates, and bureaucrats. These cities were both expansive and outward-looking, in part because artillery made walled cities infeasible. This encouraged these cities to spread into the countryside, as their security increasingly came to rely on the mobilization of armed citizens or mercenaries. In contrast to the walled-in city of the imperial era, the producer city’s walls were moved back, and new populations were absorbed into suburbs, much like in the modern city.

THE RISE OF THE INDUSTRIAL CITY

The modern city emerged from the producer city but in ways fundamentally transformed by the Industrial Revolution. Futurist and author Alvin Toffler points out that this “second wave,” or industrial, society accelerated urban density and concentration, in part due to the need to keep the workforces of new factories and associated businesses in close proximity. It did so by “stripping the countryside of people and relocating them in giant urban centers.” This was most notable in Britain in the centuries leading up to the Industrial Revolution. Britain’s urban population grew 600 percent between the dawn of the 17th century and that of the 19th century, six times the country’s overall rate of increase.

The capitalist-driven industrial city exacted a huge toll, at least initially, on its residents. Artisans who had been living in smaller villages and towns moved into cities that served as homes for giant factories. Many came to the city not for love of adventure or opportunity but due to dramatic changes in the pattern of land ownership in the countryside, particularly in Britain after the Enclosure Act of 1801, which took property that had been considered common and placed it under private ownership. As we see today in the megacities of the developing world, this sparked an urban migration as farmers lost access to fields and pastures.

Once in the city, migrants often found conditions harsher than when they lived in smaller towns or villages; their life spans were shortened by crowded conditions, incessant labor, and lack of leisure. Yet at the same time, a rising affluent class enjoyed unprecedented wealth and access to country estates that allowed them to skip the worst aspects of urban living, particularly in the summer. “The townsman,” noted one observer of Manchester and London in the 1860s, “does everything in his power not to be a townsman and tries to fit a country house and a bit of the country into a corner of the town.”

Conditions were so hard for the working classes—and the wealth of the upper classes so great—that roughly 15 percent of London’s population worked in domestic service while an estimated 35 percent lived in poverty. For those who did not have the chance to live in the relative comfort of “downstairs,” life became, as one doctor observed, “infernal,” made much worse by “vile housing conditions.” Death rates soared well above those seen in the British countryside by as much as 40 percent. The German observer Friedrich Engels notes in his searing 1845 book, The Condition of the Working Class in England, that cities like Manchester and London were marked by “the most distressing scenes of misery and poverty to be found anywhere.” Crowding and density, he noted, had an impact on the character of British city dwellers: “The more that Londoners are packed into a tiny space, the more repulsive and disgraceful becomes the brutal indifference with which they ignore their neighbours and selfishly concentrate upon their private affairs.”

Later, these conditions also spread to North America, despite the continent’s ample landmass. As early as the 1820s, slums where whole families were confined to a room or two were spreading in cities such as Cincinnati. In the 1850s, a local reporter found families in that city clustered in a “small, dirty, dilapidated” tenement room, containing “confused rags for beds and a meager supply of old and broken furniture.”

Overcrowding was considerably bad in the older Northeast cities, particularly in New York City, and the achievement of homeownership extremely rare. Densities on New York’s Lower East Side reached as high as 100,000 an acre in the late 19th century, which was equal to those in inner London, Paris, and even Bombay, according to historian Robert Fogelson. Meanwhile, Chicago, the industrial hub of the era, was described by one Swedish visitor as “one of the most miserable and ugly cities I have seen in America.” Yet people, largely immigrants, continued to go to Chicago, making it the fastest-growing large city of its time.

It was not until later in the 19th century—and even more so in the 20th century—that many of the depravities of the early industrial city diminished. Living standards improved, as did life expectancy and the quality of housing. These advancements came in part as a result of reform movements that pushed for improvements in hygiene and sanitation, as well as for the development of parks. But perhaps the most important answer to the ills of the industrial city came about—in a manner many thought, and continue to believe, unsuitable—through urban expansion into the countryside.

ONE OPTION: THE RISE OF SUBURBIA

Some early progressive reformers, such as H. G. Wells, advocated the dispersion of the population into the periphery as a means to improve the lot of urban residents. As early as the mid-19th century, London was already spreading out, losing density in its core as middle- and working-class people sought out a less cramped, more pleasant existence. In many cases, the new locales also gave them easy access to employment, which was growing more rapidly in the suburbs. Between 1911 and 1981, the population of inner London declined by 45 percent. Similarly, by the 21st century, the inner arrondissements of Paris lost three-fourths of their population in 1860.

This movement also included attempts to create what the British visionary planner Sir Ebenezer Howard labeled the “garden city.” Horrified by the disorder, disease, and crime of the early 20th century industrial metropolis, he advocated the creation of “garden cities” on the suburban periphery. These self-contained towns, with populations of roughly 30,000, would have their own employment base, neighborhoods of pleasant cottages, and rural surroundings.

Determined to turn his theories into reality, Howard was the driving force behind two of England’s first planned towns, Letchworth in 1903 and Welwyn in 1912. These garden cities were meant to be planned, self-sufficient communities surrounded by “greenbelts,” which included proportional areas of residence, industry, and agriculture. Howard’s approach, focusing on the needs of normal citizens, was in sharp contrast to not only the denser grandiosity brilliantly expressed by Napoleon III’s Paris but also to Hitler’s proposed brutalist Germania, the socialist cities of Eastern Europe, and the ambitions of some of today’s retro-urbanists. In contrast, Howard saw instead “the great value of little things if done in the right manner and in the right spirit.” By the late 19th century, Howard’s “garden city” model of development soon influenced planners around the world—in America, Germany, Australia, Japan, and elsewhere. In the United States, innovative urban thinkers—such as Frederick Law Olmsted—suggested the idea of building at a modest density in a multipolar environment built around basic human needs.

The new suburban ethos fit well in America. If anything, as Alexis de Tocqueville and others noted, Americans had a peculiar penchant for settling in small towns and villages. Contemporary suburban critics and visitors like Tocqueville, particularly those from Europe, denounced the sameness that characterized the country’s seemingly endless progression of smaller towns. The auto-centered nature of today’s metropolis reflects the essentially pragmatic and functional orientation common to American settlements.

By the ’20s, noted National Geographic, the United States were “spreading out.” Once a nation of farms and cities, America was being transformed into a primarily suburban country. No longer confined to old towns or “streetcar suburbs” near the urban core, subur- banites increasingly lived in ever more spread-out new developments such as Levittown, which arose out on the Long Island flatlands in the late ’40s and early ’50s. The suburbs, noted historian Jon C. Tea-ford, provided more than an endless procession of lawns and carports as well as “a mixture of escapism and reality.”

Although much of this building was uninspired, there were attempts to develop a better kind of community. One of the earliest and most innovative examples emerged in 1929 with the development of Radburn, New Jersey. Visualized as “a town for the motor age,” the community offered a wide range of residential units, with interior parklands and access to walkways. Car and pedestrian traffic was to be strictly separated, with houses grouped around cul-de-sacs with a small access road. To Lewis Mumford, Radburn represented “the first departure in city planning since Venice.”

Radburn focused on creating a secure and healthful environment for the residents. There were extensive recreation opportunities for the community, and the town emphasized providing an ideal environment for raising children. Initially planned to house 25,000 people, the Radburn development sadly was derailed by the Great Depression, which drove the builder into bankruptcy. Today, the city houses some 3,100 residents.

The architects of the New Deal also embraced suburban development. Early efforts to develop garden cities in America received a huge boost during the New Deal, which led to the construction of the first great master-planned communities—Greenbelt, Maryland; Greenhills, Ohio, near Cincinnati; and Greendale, Wisconsin, outside Milwaukee. These communities were designed with offices, industrial facilities, parks, and playgrounds. Provisions were also made for a diversity of housing units and income groups.

Eventually, these federal efforts were stymied by strong opposition from builders and conservatives who denounced them as “communist farms.” Plans to build some 3,000 such towns were never realized. Yet after the war, the principles behind such places were observed in the breach as massive demand, fueled by new federal loan programs, led to the building of massive conventional production suburbs that incorporated a few of these principles.

Even without the planned towns, the movement of people into the suburbs—which took place with both government assistance and the enthusiastic participation of the populace—was great enough to shrink the industrial city. Inner-city areas, which had constituted half of metropolitan populations by 1950, have dropped to barely 25 percent today. The prospect of single-family houses within the metropolitan region, once reserved for the more affluent, was suddenly within reach of most working-class families.

THE TRANSACTIONAL CITY—AND THOSE LEFT BEHIND

By the ’50s and ’60s, the growing popularity of suburbs—for both businesses and residents—generated a harsh reaction from urbanist intellectuals such as Jane Jacobs, who saw the suburbs taking the middle class away from what they perceived as a socially and culturally richer experience in the city. It also led some developers and city officials to find ways to resuscitate their city cores, an effort that continues to this day. Some of the early attempts to reinvent the city center worked, notably in more attractive “legacy” cities—such as New York, Chicago, Boston, and San Francisco—which possessed a strong trading tradition, great universities, unique architecture, and attractive physical settings. This approach was not as effective, generally, in cities whose origins lay in the manufacturing era or whose demographics and economic structures were not ideally suited for the transition to an information-based economy.

Those places that managed to emerge triumphantly out of the wreck- age of the industrial era were no longer defined by smoke-belching industrial plants. The symbol of the new successful city was the high-rise office or residential tower, the arts district, and other high-end amenities.

The visionary urbanist Jean Gottmann envisioned the emergence of what he called “the transactional city” over three decades ago. Like cities such as Amsterdam and Venice in the early modern period, which managed the trade and financial needs of vastly larger territories, these cities would benefit from the need for the production of information and the coordination of both services and finance in a globalized economy. Gottmann predicted that the suburbs would also grow, but he placed emphasis on the strong expansion of city cores, which he said would benefit most from serving as “crossroads for economic transactions.”

In the emerging urban hierarchy, the best-positioned cities—New York, San Francisco, Boston—were able to rebound smartly, often through redevelopment and the cultivation of knowledge-based industries. This often also had the effect of displacing whole communities, primarily working-class whites and African Americans, while replacing them with higher-income, more educated residents. But the revitalization efforts of the ’70s and ’80s that succeeded in places like Boston’s Quincy Market, notes historian John C. Teaford, were notably less successful in far less historically blessed places, such as Buffalo, Cleveland, and Toledo. While some cities were able to transform themselves into successful information-era hubs, many other cities—and their residents—were left behind.

By the dawn of the 21st century, 70 percent of children in New Orleans, nearly 60 percent in Cleveland, and 41 percent in Baltimore lived in poverty. Cities such as Chicago, Cleveland, and Detroit continued to lose population. Detroit, a century earlier renowned for its “broad and cleanly streets,” presented arguably the worst-case scenario, losing most of its residents as both industry and the middle class decamped for the periphery and other parts of the country. “This,” author Scott Martelle wrote about Detroit, “is what the abject collapse of an industrial society looks like.”

ANOTHER OPTION: THE SOCIALIST CITY

Some planners sought to remedy the predicament of the industrial city without suburbanization. Their response to the failures of industrialism drew from a socialist ideology, which some thought would aid them in creating cities along more equitable lines. Like some of today’s retro-urbanists, socialist city-builders evolved their own planning “religion,” albeit in a more oppressive form, to address the problems associated with growing cities.

The socialist vision of the city found early expression in the writings of German sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies. Heavily influenced by Marx, Tönnies envisioned a future in which the entire world would become “one large city” run not by the populace in general but “by thinkers, scholars, and writers” who would construct and control this planetary metropolis.

Once established, the Soviet Union provided the primary model for this new urban ideal. Under Joseph Stalin’s rule from 1929 to 1953, numerous “socialist cities” were built by importing the peasantry from the countryside, sometimes through coercion and forced migration. This was intended both to further enlarge the working class and to accelerate the transformation of the Soviet Union into an industrial superpower. Built from scratch, the new factory towns “were intended to prove, definitively, that when unhindered by pre-existing economic relationships, central planning could produce more rapid economic growth than capitalism.”

At the same time, large existing cities also were transformed to fit the model of “socialist cities.” As they sought to rebuild the former Saint Petersburg, Petrograd (soon to be renamed Leningrad), and Moscow, the Bolsheviks quickly occupied many of the old mansions and fashionable apartments of the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie, whom they had overthrown. But the rest of the population was instructed to live as the party required. As novelist Aleksey Tolstoy suggested, this was a society where “everything was cancelled,” including, he noted “the right to live as one wished.”

The new Communist rulers sought to build their urban areas by obliterating the civic past—not too unlike, as we’ll see, the redevelopers in the West during the ’60s and ’70s. Stalin, for example, demolished the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, which had been com- pleted in 1882 after 40 years of construction. In its place, the Soviet regime constructed the new Palace of the Soviets. Thousands of other historic buildings also went down under Bolshevik edicts. “In reconstructing Moscow,” proclaimed Nikita Khrushchev in 1937, “we should not be afraid to remove a tree, a little church, or some cathedral or other.” When his own architects asked him to spare some historical monuments, the future Soviet leader responded that his crew would continue “sharpening [their] axes.”

But the goal was not merely to transform the physical city. Socialist planners also saw cities as the ideal place to create a new kind of urban person, what some critics labeled Homo sovieticus, or “Soviet Man.” As one historian wrote, the socialist city was to be a place “free of historical burdens, where a new human being was to come into existence, the city and the factory were to be a laboratory of a future society, culture, and way of life.”

Socialist planners sought to achieve this new urban paradigm by constructing cities along lines that would promote their notion of community. Nurseries and preschools were built within walking distance of residential areas. Theaters and sports halls were also placed nearby. Instead of individual kitchens, communal eating areas were developed. Private space was minimized while planners constructed wide boulevards crucial for marches and impressive public structures. Sadly, the construction was often shoddy—despite Soviet propaganda depicting ideal construction sites with happy workers and well-managed cities with happy families. “In the new socialist cities,” writes historian Anne Applebaum, “the gap between the utopian propaganda and the sometimes catastrophic reality of daily life was so wide that the communist parties scrambled constantly to explain it away.”

What did a “socialist” city look like? It certainly did not resemble contemporary suburbs in the West. The new model—much like that of today’s retro-urbanists—favored multistory apartment blocks over leafy suburbs. Alexei Gutnov, one of the authors of the book The Ideal Communist City, acknowledged that suburban development provided “ideal conditions for rest and privacy … offered by the individual house situated in the midst of nature …” But this approach, he decided, did not fit the communist ideal of a more egalitarian, socially reconstructed society. Gutnov feared that the highly private nature of such housing might lead the citizen to “separate himself from others, rest, sleep, and live his family life,” which would make it harder for the state to steer him toward the proper “cultural options.”

As part of its commitment to equality, the socialist city sought to provide equal mobility for all residents, with each neighborhood being at equal walking distance from the center of the community and from the rural area surrounding it. Like the radiant city of Le Corbusier, these dense developments would be surrounded by open land on at least two sides, creating a green belt. Not surprisingly, socialist planners also strongly preferred public transportation over privately owned vehicles, high-density apartment housing over detached private homes, and maximizing common areas over private backyards.

These notions, notes Applebaum, were quickly adopted by the Soviet satellites in Eastern Europe, who sought out “the destruction of the property-owning classes,” which included small homeowners. Influenced by modernist ideas, identical pre-fab tower blocks in park- like settings were mass produced all over the Soviet Union and its satellite states. CalledPlattenbau in German and paneláky in Czech and Slovak, these panel buildings were constructed of pre-fabricated, pre- pressed concrete and often poorly constructed. One-third of all Czechs still live in a panelák.

One particularly sad example of socialist planning—and its authoritarian Nazi counterpoint—could be seen in and around Berlin. In the prewar era, Berlin’s raucous lifestyle and socialist leanings offended both conservatives and Nazis. The Nazi Party leader for Berlin (and later, Hitler’s propaganda minister), Joseph Goebbels, initially denounced the city as “a sink of inequity.” But as the capital became synonymous with the Third Reich, Goebbels began to describe it as “magnificent,” “electric,” and a city that exhaled “the breath of history.” Hitler himself, to the consternation of his völkisch, rural-oriented supporters, centralized power in the capital and determined to make Berlin the most magnificent city in Europe. Before being halted by their defeat in World War II, the Nazis planned to turn Berlin into a monumental city of Germania, which would have been one of the most extensive urban building projects in history.

The Communist inheritors of the then-ruined eastern half of Berlin may have shared Hitler’s passion for authoritarian ideology, but unlike the Nazis, they never possessed enough resources to rebuild the city. Following the Bolshevik model, party leaders seized what was left for their own good, absconding with country estates and the few remaining comfortable city apartments. But they also followed Soviet ideas in how they constructed the urban environment for their supposed masters, the proletarians. East German architects and planners made the obligatory pilgrimages to Moscow, Kiev, Leningrad, and Stalingrad to find out what a socialist city looked like. They soon learned that their Soviet colleagues, among other things, preferred large apartment blocks to tree-lined, lower-density suburbs.

The results were depressingly bleak. The city, with its dense apartment blocks and blocky office buildings, reflected much of the modernist tradition but in a particularly uninspired and dehumanized manner. As anyone who visited there at the time could recall, socialist Berlin loomed as a very gray city with little charm; once the East German state disappeared, many residents, including those in Leipzig, left for the more frankly capitalist cities in the West.

THE EMERGENCE OF THE NEW CONSUMER CITY

Even as many of the old industrial cities continued to fail—not only in America but also in eastern Asia and Europe—Gottmann’s “transactional city” burgeoned in pockets around the world. By the ’80s, these revitalized cities were beginning to newly invigorate the urban role as centers of consumption and wealth.

In this new calculus, a city’s value had less to do with its physical geography—for example, access to rivers or power sources—than with its ability to attract high-service industries and a workforce that could operate them. Unlike the more industrially based cities throughout the world, which were left with little after the factories closed, these cities enjoyed a smoother transition into the information era. The new consumer city also represented, fundamentally, a city of choice—that is, a place where certain consumers came not so much for opportunity but rather to partake in the pleasures of high-end urban life.

Factories in Detroit and Manchester lay idle and useless for decades, but the centers of the transaction economy often succeeded by repurposing the residue of the old industrial era. In some places, old warehouses and factories were brilliantly transformed into areas for higher-level services as well as restaurants, bars, and retail shops. This was particularly true along rivers and lakefronts. Similarly, churches, which had served as the fulcrum for Renaissance urbanism, were shut down, and even more will be in the future. It’s been predicted that in the next 20 years, some two-thirds of the 1,600 churches now operating in Germany will close—but they may find new life as boutiques, entertainment venues, or luxury condos.

This trend started as early as the ’60s. English author and journalist A. N. Wilson, for example, wrote about the shift in London from its dock and manufacturing economy to one dominated increasingly by media and finance, as well as the shift toward more luxury con- sumption, clubs, and shops. This new urban economy, Wilson noted, allowed London, with its concentration of business, financial services, and media, to remain remarkably vibrant, while the old industrial cities of the Midlands, like their counterparts elsewhere, essentially lost their fundamental purpose and faced a secular decline from which they have not recovered.

With its rich array of cultural amenities, the new consumer city exercises an almost magnetic attraction for the very wealthy, students, and people at the early stages of their careers. Its core economy revolves around the arts and high-end managerial and financial positions. Modern, post-industrial London, observed English novelist Ford Madox Ford, is irresistible to some as it “attracts men from a distance with a glamour like that of a great and green gaming table.”

This trend evolved, if anything, even more profoundly in America’s premier city, New York. In 1950, notes historian Fernand Braudel, New York was “the dominant industrial city in the world,” populated largely by small, specialized firms that often employed 30 people or fewer. Collectively, they employed a million people and were key to the rise of many immigrant families, including my own. Today, the city has fewer than 200,000 people working in industry; the loss of these firms, Braudel notes, left “a gap in the heart of New York which will never be filled.”

Yet if the industrial heart was emptied, New York was not without recourse. The old industry base was supplanted by the “information economy,” which as early as 1982 already accounted for the majority of Manhattan’s jobs. So while plants were slowly going dark throughout the city, new office towers were rising over Gotham. In many ways, this transformation built on New York’s early history of being, first and foremost, a trading and port city. The difference was that the primary raw material was no longer in trading commodities but rather in harnessing skills in the production of information.

This successful evolution led some, including Terry Nichols Clark, to suggest that urban success depends not so much on new office construction, or even corporate expansion, but on the locational decisions of individuals who rely largely on the city’s cultural and lifestyle attributes. Clearly, locational preferences play an important role in sustaining these cities. The same spectacular scenery of such cities as Seattle or San Francisco that appeals to visitors also lures well-heeled populations who can live every day amid the splendor that most experience only as tourists.

The new consumer city depends upon attracting those who seek out the thrills of urban life—a trend that Clark defines as “the city as entertainment machine.” In this approach to urbanity, a city thrives by creating an ideal locale for hipsters and older, sophisticated urban dwellers, becoming a kind of adult Disneyland with plenty of chic restaurants, shops, and festivals. In Clark’s estimation, amenities and a “cool” factor make up the essence of the modern city, where perception is as important as reality, if not more so. He suggests: “for persons pondering where to live and work, restaurants are more than food on the plate. The presence of distinct restaurants redefines the context, even for people who do not eat in them. They are part of the local market basket of amenities that vary from place to place.”

THE NEW GEOGRAPHY OF INEQUALITY

In this new consumer city, the role that priests and aristocrats played in imperial cities has been assumed by the global wealthy, financial engineers, media moguls, and other top business executives and service providers. One thing the new consumer city does share with its historic counterpart is a limited role for an expanding middle class.

Some of this stems from the structure of the successful transactional city. In recent decades, these cities have grown two ends of their economies: an affluent, well-educated, tech-savvy base and an ever-expanding poor service class. Mass middle-class employment is fading. Unlike in the ’60s and ’70s, these cities have not produced anything like the office towers built to house middle managers, clerical staff, and others who are neither rich nor poor. In fact, by 2014, office space was being built at barely one-tenth the level in American cities as that of the ’80s. Instead, the new consumer city expresses itself largely through the construction of residential structures, aimed largely at the high-skilled workforce as well as a nomadic population made up of wealthy, highly gifted, or top specialists. The growth of these cities, note historians John Logan and Harvey Molotch, was less a result of local economic expansion as it was of the cities’ ability to use their capital to acquire firms from elsewhere, which helped secure their place in “the hierarchy of urban dominance.”

This frankly elitist vision of the city is widely embraced by many urban developers and politicians. Former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg suggests that today, a successful city must be primarily “a luxury product,” a place that focuses on the very wealthy, whose surplus can underwrite the rest of the population. “If we can find a bunch of billionaires around the world to move here, that would be a godsend,” Bloomberg, himself a multibillionaire, says. “Because that’s where the revenue comes to take care of everybody else.”

This reliance on the rich, notes a Citigroup study, creates an urban employment structure based on “plutonomy,” an economy and society driven largely by the wealthy class’s investment and spending. In this way, the playground of these “luxury cores” around the world serve less as places of aspiration than as geographies of inequality. New York, for example, is by some measurements the most unequal of American major cities, with a level of inequality that approximates South Africa before apartheid. New York’s wealthiest 1 percent earn a third of the entire municipality’s personal income—almost twice the proportion for the rest of the country.

Other luxury cores exhibit somewhat similar patterns. A recent Brookings Institution report found that virtually all the most unequal metropolitan areas—with the exception of Atlanta and Miami—are luxury-oriented cities, including San Francisco, Boston, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC. As urban studies author Stephen J. K. Walters notes, these cities tend to develop highly bifurcated economies, divided between an elite sector and a large service class. “This,” he notes, “is the opposite of [Jane] Jacobs’s vision of cities … as places they are ‘constantly transforming many poor people into middle-class people.’” These trends are particularly notable in places such as Kendall Square in Cambridge, just across the Charles River from Boston. The expansion of technology and biomedical firms has transformed this traditionally working-class redoubt into an increasingly bifurcated society divided between the affluent and highly educated and a large poor population. The median price of a one-bedroom apartment in Cambridge is $2,200 a month, according to the online real estate company Zillow—more than many local residents make in a month. As the Boston Globe reports:

“As global pharmaceutical companies build new labs, Internet giants Google and Twitter expand, and startups snap up office space at ever-higher rents, families living in the shadow of the innovation economy are flocking to the local food pantry at three times the rate of a decade ago. The waiting list for public housing is double what it was five years ago. The beds in the Salvation Army homeless shelter on Massachusetts Avenue are always full.”

These patterns contradict the notion of the middle-class, family-oriented city that Jane Jacobs so evocatively raised. On the ground, as Witold Rybczynski notes, the rise of successful urban cores increasingly has very little to do with Jacobs’s romantic notions about bottom-up organic urbanism: “The most successful urban neighborhoods have attracted not the blue-collar families that she celebrated, but the rich and the young. The urban vitality that she espoused—and correctly saw as a barometer of healthy city life—has found new expressions in planned commercial and residential developments whose scale rivals that of the urban renewal of which she was so critical. These developments are the work of real estate entrepreneurs, who were absent from the city described … but loom large today, having long ago replaced planners and our chief urban strategists.”

As Rybczynski notes, the current rise of “urban vitality” derives not from the idiosyncratic, diverse, and, if you will, democratic form that Jacobs celebrated but from a more manufactured form. This is very much the experience of modern Paris, London, Brussels, Hong Kong, and Singapore, where high housing prices are driving many longtime residents and even some affluent families out of the core city and, in some cases, out of the country.

In the process, we see a city that is increasingly divided by class and provides limited options for upward mobility. In the past decade, for example, there has been considerable gentrification around Chicago’s lakefront. But during this period, Chicago’s middle class has declined precipitously. At the same time, despite all the talk about “the great inversion” with the poor replaced by the rich, it turns out that it is mostly the middle and working classes who have exited.

Urban analyst Pete Saunders suggests that Chicago is really two different cities now, with different geographies and sizes. Prosperous and greatly hyped “super-global Chicago” has income and education levels well above those of the suburban areas, but the majority of city residents live in “rust belt Chicago,” with education and income levels well below suburban levels. “Chicago,” Saunders says, “may be better understood in thirds—one-third San Francisco, two-thirds Detroit.”

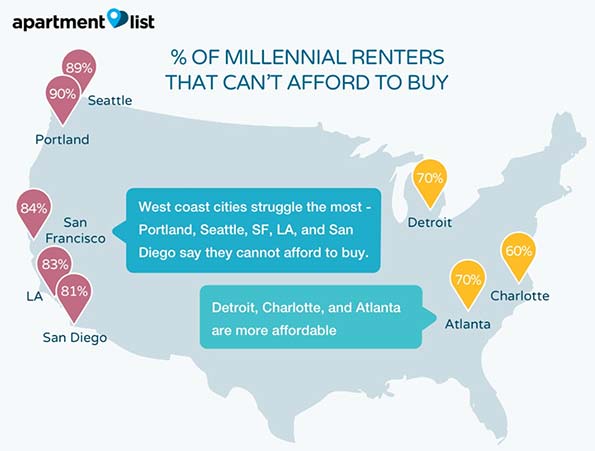

It’s ironic that many of the cities that have done best in the post-industrial era have also been those that have become ever less diverse; they have evolved in ways that contradict Jacobs’s idealized urbanity, in which dense neighborhoods seemed to be the most permanent as opposed to the most transient. Successful transactional centers increasingly have less room for either the poor or the middle-class families who have traditionally inhabited them. San Francisco’s black population, for example, is a fraction of what it was in 1970. In Portland, the nation’s whitest major city, African Americans are being driven out of the urban core by gentrification, partly supported by city funding. Similar phenomena can be seen in Seattle and Boston, where long-existing black communities are gradually disappearing.

Whatever their successes, the transactional cities have not found a way to address the problem of inequality, the role of families, or the preservation of the urban middle class. Most shocking of all, the shift to an information-based economy has not succeeded in eliminating poverty. Indeed, during the first 10 years of the new millennium, neighborhoods with entrenched urban poverty actually grew, increasing in numbers from 1,100 to 3,100 and in population from 2 to 4 million. “This growing concentration of poverty,” note urban researchers Joe Cortright and Dillon Mahmoudi, “is the biggest problem confronting American cities.”

TOWARD A NEW URBAN PARADIGM

The transactional city model, it is clear, does not provide a workable urban future for the vast majority of society. For one thing, due to their high prices, these cities are profoundly challenged in providing what most residents of the metropolis actually want: homeownership, rapid access to employment throughout the metropolitan area, good schools, and human-scaled neighborhoods.

Instead, the transactional city represents a profound sociological departure from the more democratic form of urbanism that emerged first in the 17th century and again in the 20thcentury. Their appeal is not for middle-income families or ambitious newcomers from out- side but rather for those attracted to—and able to afford—what Terry Nichols Clark refers to as the urban “basket of amenities.” As we’ve seen, these primarily include the educated young, the childless affluent, and, most particularly, the very wealthy.

The current urban discussion all too often ignores the issue of how to offer opportunity to the vast majority of the population. In a world where most people live in cities and towns, all efforts should be made to make these places accessible and livable for the vast majority of citizens. The dense, luxury city model may work well for certain people at particular points in their lives, but the greatest challenge remains, as it was in the past, accommodating the aspirations of the majority, who have long gone to the city for opportunity, cultural inspiration, and a sense of identity.

GENUINE SUSTAINABILITY

No doubt the luxury core model will continue to flourish in places, particularly for the well-heeled and those located in a limited number of historic cities that boast historical structures, unique amenities, and usually excellent mass transit. But this paradigm is not applicable, in any case, to a whole city—even a New York or London—where most people live outside the glamorous districts. If we want an urbanism that works for most, cities need to develop a very different focus, emphasizing such things as economic growth and opportunity—a geography that increases the opportunities for a broad array of citizens.

Properly defined, sustainability must extend beyond the environment, around which the term “sustainability” is usually hung, to a broader concept that includes the health of the entire society. In the past, the city—and later the suburb—provided “a profoundly democratic phenomenon,” which upgraded the living conditions of the middle and working classes. In contrast, the evolution of the new consumer city works against the improvement of middle- and working-class residents. Planning policies to restrict peripheral growth, so favored in the luxury cities, also serve to raise rents and home prices, as is most evident in highly regulated places like California, Australia, and the United Kingdom.

In this sense, then, we need to look at social sustainability—that is, the preservation and expansion of the middle class—as a critical value for the future of society and its overall health. Building out into the periphery has provided this option more than any other model. “Sprawl,” notes author Kenneth Kolson, “serves their [the middle class’s] interest far more than the growth girdles and other market restraints of ‘smart growth.’”

What we need is to extend our definition of “sustainable” to go beyond the lower standards of living and higher levels of poverty that would occur from forcing human beings into ever smaller, and usually more expensive, places. The attempt to reduce the space and privacy enjoyed by households is not “progressive” but fundamentally regressive. In this sense, notes British author Austin Williams, sustainability has evolved into “an insidiously dangerous concept, masquerading as progress.” By limiting housing options and focusing on the most affluent quarters, sustainability advocates sometimes suggest policies that make things more expensive for the middle and working classes. They also make the formation of families increasingly difficult. In this most basic biological sense, Williams says, “the ideology of sustainability is unsustainable.”

Instead of focusing only on environmental and design concerns, we need to place far more emphasis on the human factor as we construct and develop our cities. Residents may, and generally do, desire cleaner air and water, but they may not think this also means they have to accept crowded conditions that they may find depressing, too expensive, and inimical to family formation.

Perhaps most maddening is that many of those who most actively push densification do not have to live with the consequences. Increasingly, those calling for more densification are people who, as one Los Angeles newspaper found, enjoy the very lifestyle—in gated communities and large houses located far from transit routes—they wish to eradicate for others.

The ultimate absurdity of this new approach to urbanity was on display at the World Economic Forum’s 2015 Davos meeting, epitomized in the focus on climate change by people who used some 1,700 private jets to attend the Swiss event. The people blowing fuel on private jets somehow feel empowered to ask everyone else to live more modestly. One has to wonder about Davos-goers like billionaire real estate investor Jeff Greene, who says that to fight climate change, America needs to “live a smaller existence.” This coming from a man who lives ultra-large with five houses, including an un-small $195 million Beverly Hills estate that may be the country’s priciest residence.

SEARCHING FOR THE HUMAN CITY

In many ways, we are faced with a crisis that parallels that of the industrial city, with ever-widening inequality, widespread poverty, and social alienation.

Frank Lloyd Wright came up with what may be seen as the most ambitious vision in response to the current emphasis on ever-increasing density. Wright detested the way high-rise buildings cast shadows on the urban landscape, and in his proposals for Broadacre City, made in 1958, he posited a model in which many urban functions were dis- persed into the countryside. In sharp contradiction to Le Corbusier, Wright saw the densification of cities as a “destructive fixation.” Universal electrification and modern transportation, he argued, had made densification unnecessary and made possible a greater dispersion of cities. He equated decentralization with democratic principles and with the provision of a better life for those strangled by “urban constriction.” Wright, perhaps somewhat impractically, thereby proposed “an acre to each individual man, woman and child.”

Wright’s ideas, or those of Ebenezer Howard, for that matter, were never fully adopted, but these principles—developed in reaction to the industrial city—remain highly applicable in the information age as well. The desire for space, light, and access to green spaces has not changed; these are universal and intrinsically human desires. This is true for the low-density cities of the West but also, if anything, more imperative in the dense cities of Asia, where most people do not have access to their own backyards.

Great cities that want to attract and retain families must maintain that spiritual nourishment that comes from contact with nature. Olmsted’s vision of Central Park, for example, was to provide working-class families “a specimen of God’s handiwork.” Today, many of the most ambitious programs for park-building are taking place in suburbs, such as Orange County’s Great Park, which is slated to be twice the size of Central Park, or in sprawling family-friendly cities, such as Raleigh’s nearly completed $30 million Neuse River Trail, which cuts through 28 miles of heavily forested areas. There’s Houston’s rapidly developing bayou park system and Dallas’s vast new 6,000-acre reserve along the Trinity River that easily overshadows New York’s 840-acre Central Park. These ambitious new parks often start close to the urban core but also provide open space for the widely dispersed settlements attached to them.

This suggests a radically different approach to the urban future, one that can be not only “greener” but also, most importantly, better for people and their families. In the end, it is not the magnificence of a city that matters, or its degree of hipness, but how well people live, both in terms of their standard of living and their ability to rise economically. It is a question of accomplishing those things that have made cities work in the past: an expansive economy, thriving families, and a powerful sense of place.

![160506-kotkin-livable-cities-embed]()

Agate B2

‘The Human City: Urbanism for the Rest of Us’ by Joel Kotkin. 302 p .Agate B2. $16.13

In reality, for most residents of cities, life is not about engaging the urban “entertainment machine” or enjoying the most spectacular views from a high-rise tower. To them, the goal is to achieve residence in a small home in a modest neighborhood, whether in a suburb or in the city, where children can be raised and also where, of increasing importance, seniors can grow old amid familiar places and faces. As the Southern California writer D. J. Waldie writes of his home in working-class Lakewood: “I believe that people and places form each other … the touch of one returning the touch of the other. What we seek, I think, is tenderness in this encounter, but that goes both ways, too. I believe that places acquire their sacredness through this giving and taking. And with that ever-returning touch, we acquire something sacred from the place where we live. What we acquire, of course, is a home.

Such a notion of “home” remains generally undervalued in our current discussion of the urban form. People clustering in ever more crowded cities, living atop one another, may fulfill the ambitions of corporate leaders, urbanist visionaries, and planners. But in the end, such ambitions may not fulfill, for most people, what a less congested place or a house cooled by even a touch of green and trees might provide. As the world urbanizes, this is not merely an American or high-income country issue but one of increased global significance.

Excerpted from The Human City: Urbanism for the Rest of Us and reprinted here with the permission of the author.

This piece first appeared at The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us, will be published in April by Agate. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

![]()

, a collection of historical travel essays, and

, a collection of historical travel essays, and

Blacks are returning to southern cities, like Atlanta, drawn by economic opportunity and lower costs, especially compared with progressive cities like San Francisco, where restrictive housing policies have made living unaffordable for many. JIM WILSON/THE NEW YORK TIMES/REDUX

Blacks are returning to southern cities, like Atlanta, drawn by economic opportunity and lower costs, especially compared with progressive cities like San Francisco, where restrictive housing policies have made living unaffordable for many. JIM WILSON/THE NEW YORK TIMES/REDUX