This essay is part of a new report from the Center for Opportunity Urbanism called "America's Housing Crisis." The report contains several essays about the future of housing from various perspectives. Follow this link to download the full report (pdf).

“...a social revolution was being made, not by storming barricades, but by leaping over them.”

Seven decades ago, the great post- war American suburbanization began. The seminal development was Levittown, built on potato fields in Nassau County, outside New York City. This archetypical development, with its small houses and modest lots, helped launch a suburbanizing trend that has accounted for virtually all of the population growth in the nation’s largest metropolitan areas. Today’s new houses are at least three times the size of the early Levittown houses, but they reflect the continued preference for suburban communities over the last half century.

This essay examines the great Post-War suburbanization, incubated in Levittown and its revolutionary impact on American civilization. At the same time, there is no doubt that racial exclusion was part of the formula, abetted not only by people, communities and developers, but worst of all by governments themselves, especially the federal government. These regrettable exclusionary policies at the time also characterized virtually every walk of American life.

Yet, for the most part, millions— now including millions of minority households—are better off than they would have been without the great suburbanization. As Professional Builder magazine put it:

At a time when few working people could afford a home, Levitt helped them realize their dream, starting with servicemen and women returning from the war.

Levitt brought mass production techniques to home building, following in the mold of Henry Ford, who made automobiles inexpensive enough for middle-income households. The higher quality detached housing with yards could not have been built at low enough prices without such techniques, nor could it have been offered at such prices without the additional advantage of less expensive urban fringe land.

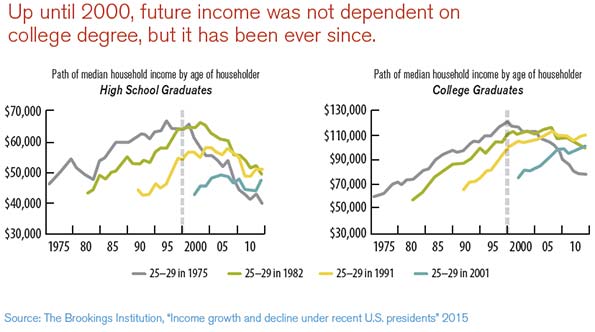

As home ownership expanded, perhaps the most important result was class mobility. In this period the

American middle class expanded as never before and home ownership skyrocketed.

This might seem cause for celebration, but an influential group of planners and intellectuals damned it from the very start. These, whom this essay will refer to as the retro-urbanists, tend to idealize the pre- automobile city, which has largely been replaced not only in the United States but in virtually all high income countries. German academic Thomas Sieverts called these views “criticism rooted in an ideological concept of the city.”

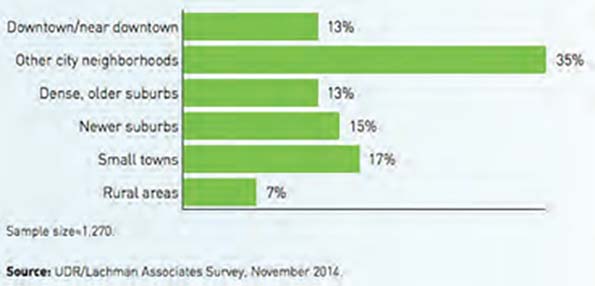

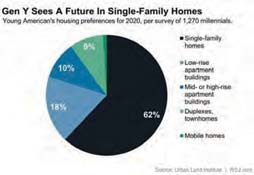

As retro-urbanists have sought to stop or even reverse suburbanization, people stubbornly have continued to choose the suburbs overwhelmingly,

not materially moved by the nostalgia so often keenly evident among pundits and planners. So far these efforts have achieved only modest gains, mostly in a handful of states, where the retro-urbanists have had sway, but at great cost to the middle class. \

In the meantime, however, the housing affordability represented by Levittown and most of the suburban development since World War II has had its reward in a “property owning democracy,” which legendary urban planner Peter Hall of University College, London described as a principal objective of public policy.

THE SITUATION IN 1946

The America of 1946 was much different than today. The United States had just emerged from the world’s most destructive war, emerging as the dominant world power and producer (the latter principally because other competitors had experienced massive destruction). Yet, despite this position, Americans in 1946 experienced a far lower standard of living and greater level of poverty than today.

World War II had made it possible, finally, for the nation to emerge from the Great Depression, which had been characterized by unprecedented levels of unemployment and economic stagnation.

Housing was overcrowded, especially in the cities and living standards were far below present standards.

Michael J. Bennett describes the situation:

“Home was usually a three or four story tenement or apartment house, a two, three or four-decker for as many families or a single-family shotgun house with tiny rooms off

a single corridor, so-called because the shotgun could be fired down the corridor without hitting anyone. Only the better-off live in fairly spacious houses on the outskirts of town. Even those houses, however, had small tiny front lawns and were separated from each other by little more than a hedge between gravel or partially paved driveway.”

Bennett goes on to indicate that only the very rich took showers in the morning, “because they were the only ones with showers” and that “Many families had to share toilets and sinks as well as tubs with people living on the same floor.”

The nation’s returning soldiers, in unprecedented numbers, would experience a better America, with better lives. There was also a concern among policymakers that the failure to facilitate opportunities for returning soldiers could result in social upheaval or even revolution in the worst case. Some noted the social disruptions that occurred following World War I, in countries like Russia and Germany. There was great interest in trying to ensure that this did not happen in America.

Just before the end of the war, Congress passed and President Roosevelt signed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, called the “GI Bill of Rights,” which provided assistance to veterans, especially improving access to housing and access to higher education. At the same time, the Federal Housing Administration was aiding home purchases for households not eligible for the “GI Bill.”

LEVITTOWN AND THE GREAT POST-WAR SUBURBANIZATION

America’s status as an urban nation was still relatively new as it headed into World War II. The US urban population had not exceeded that of rural areas until the 1920 census. By 1940, the urban population was approximately 57 percent, according to Census Bureau data, well below the 81 percent of 2010. In the following seven decades almost all of the nation’s population growth would occur in America’s urban areas.

Following the legacy of the New Deal, it was expected that new housing would be largely provided by government. The home ownership rate had dropped to 44 percent from its peak of 48 percent in 1930.ix It was assumed that the new

housing would be for renters rather than for homeowners. The reality turned out much different.

One entrepreneur is widely heralded as having blazed the trail for the suburbanization that emerged following World War II, William Levitt, and his company Levitt and Sons. A home builder before the war, in 1947 he established the legendary Long Island, New York, community of Levittown. Levitt revolutionized homebuilding in the United States after having applied factory building techniques to the provision of wartime (defense) housing.

Levitt began to build rental housing on the suburban fringe of New York City, but switched to owned housing as federal programs and his house production techniques together create auspicious conditions for selling single family houses.

In 1947, Levitt marketed four different models. Eventually the seven square mile development would contain more than 17,000 new houses. The houses were small, at 750 square feet. There were

four rooms, the kitchen, the living room and two bedrooms, all on a single floor. The houses, however could be expanded, which many households did. There were no garages. The houses were sold for approximately twice the average wage earner’s annual pay.

Little more than a decade after the first house was occupied, Levittown achieved a population of 65,000 (1960 census). This was near the peak of Levittown’s population, since with virtually all of the land occupied and a future of declining household size, reductions in population were inevitable. By 2010, the population had dropped to 52,000. However Levittown remained a vibrant community from the beginning and remains so today.

Levitt took the concept to other metropolitan areas as well. A Levittown featuring somewhat larger houses was developed in the Philadelphia suburbs of Willingboro township in Burlington County, New Jersey and in Pennsylvania’s Bucks County.

In an essay entitled “Levittown: The Archetype for Suburban Development,” historian Joshua Ruff said that: “... Levittown was about more than just the houses,” adding that it was the “…largest and most influential housing development of its time..”

Lakewood: Another important suburban community was Lakewood, located near Long Beach in the Los Angeles metropolitan area.xi The Lakewood development included 17,500 houses built between 1950 and 1953.

The houses were between 825 square feet and 1,050 square feet.xii Lakewood, which claimed to be the largest planned housing development ever, included a regional shopping center.

However, despite such important early developments, most of the new suburban housing around the nation was built by smaller home builders in the decades to come.

THE CONSUMER RESPONSE

The new suburban communities were exactly what returning soldiers and other Americans wanted. As historian Joshua Ruff put it:

Patience had been killed by 15 years of economic depression, war and an epidemic housing shortage. People wanted the full package—the affordable house, the new appliances, the suburban lifestyle—and they wanted it right away.

Kenneth Fox, of Yale University, wrote that: “The suburban development that began in the 1940s was revolutionary in two ways: it changed the type of community millions of Americans live in, and it transformed the national social class structure.”

The American middle class was about to undergo an unprecedented expansion. Before, as author Studs Terkel put it:

“The suburb, until [about 1946], had been the exclusive domain of the ‘upper class.’ It was where the rich lived. The rest of us were neighborhood folk. At war’s end, a new kind of suburb came into being.”

According to Fox: “Eventually, suburban cultural changes and white- collar status aspirations fused and produced a shift in the basis of social class differentiation. Income and style of living supplanted occupation and economic status as the parameters defining the major social classes. A broad middle class emerged, encompassing more than one half the metropolitan population in the 1970s.”

Indeed, according to Fox, middle- class became defined more as lifestyle,

rather than origins: “Increasingly, and the family that chose to buy a home in a reputedly middle-class community, behave in a middle-class matter, and maintain all appearances of the middle class, could gain acceptance in the middle class, regardless of the parents occupations.”

Levittown chronicler Barbara Kelly noted a connection between home ownership and upward mobility, indicating that it conveyed “defacto membership in middle class.” She added: “...during the years in which the government was most active in promoting home ownership, there was a marked expansion of the American middle class, which consisted largely of the definition of its parameters.”

Harvard historian Robert Fishman noted the rising affluence: “For the first time in any society, the single-family detached house was brought within the economic grasp of the majority of households.” The US may have been first, but it is not alone in having democratized prosperity.

Bennett characterized the advances, noting that “...a social revolution was being made, not by storming barricades, but by leaping over them.”

And despite claims to the contrary, most of the new suburban residents came from migration to the large metropolitan areas, not from core cities. The new suburbanites were as likely to be from a small town or the countryside as a big city.

HOUSING AFFORDABILITY: WHAT MADE IT POSSIBLE

It was the affordability of such housing that made these improvements possible. Housing remained affordable across the nation in the decades to come, with some important exceptions.

According to the US censuses of 1950 through 1970 median house values in the largest metropolitan areas were generally 3.0 or less times the median household income (the “median multiple”), with only two having a higher average (both 3.1).

At the same time, there were differences in housing affordability. As would be expected, some parts of the country were more attractive than others. Therefore, it is not surprising that house prices in the coastal California metropolitan centers of Los Angeles, the San Francisco Bay Area and San Diego were less affordable, but still remained at or below the 3.0 median multiple standard, in part due to higher incomes.

The housing bubble and bust were to come later, during which the losses in housing affordability were even greater.

Home Ownership

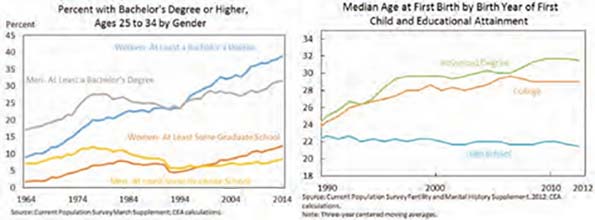

The government role here was crucial. By 1960, homeownership had reached 62 percent, well above the 44 percent of 1940. In the following three and half decades, the home ownership rate varied up and down in a range of from 62 percent to 66 percent (Figure).

Then, as mortgage eligibility was relaxed during the housing bubble, the home ownership rate rose to nearly

69 percent. Following the housing bust, it had fallen to below 64 percent by 2015.

Some retro-urbanists have characterized the comparatively recent experience of the housing bubble and bust as indicative of an overall failure of postwar US housing programs. Nothing could be further from the truth.

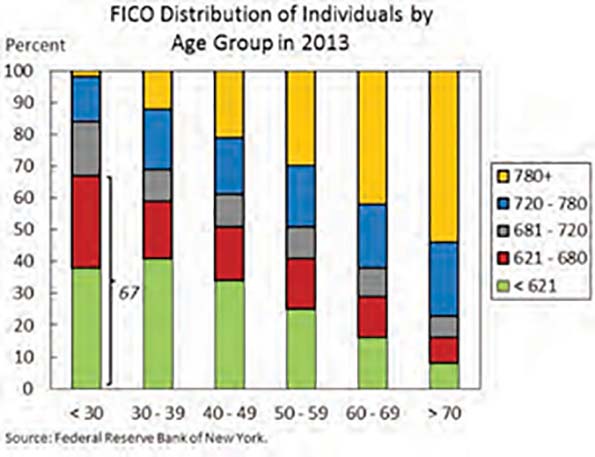

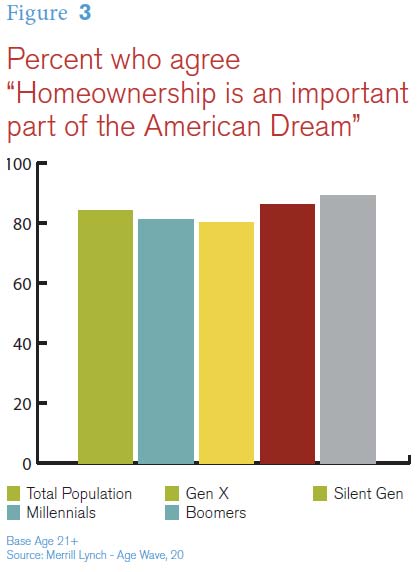

In fact, US housing programs had been instrumental in producing a significant increase in homeownership and the creation of a much broader middle-class. The evidence remains “the 60 to 65 percent level of home ownership of the 35 years preceding 1995 was sustained. Meanwhile, even after the housing bust, home ownership remains a priority among American households,xxvi including younger people. Even after the Great Recession, the aspiration for home ownership remains strong. Polling by the Demand Institute (operated by The Conference Board and Nielson) found that 77% of respondents considered home ownership “an excellent investment” (Figure).

THE RETRO-URBANIST RESPONSE

It might be expected that there would be popular and widespread acclamation of this success. Surely, the results were consistent with the principal priorities of a progressive society, at least in the historic sense, to improve the standard of living and reduce poverty.

Yet, this was not to be. Retro-urbanists, including many planners, architects and other thought leaders were nothing less than appalled. In reaction to this, the very first words in the preface of Herbert J. Gans’ The Levittowners: Ways of Life and Politics in a New Suburban Community, read: “This book is about a much-maligned part of America, suburbia...”xxix he continues to indicate that these observers of suburbia are similar to literary writing, “which often boils down to cataloguing ... Shortcomings from the author’s perspective.”

Kelly characterizes the criticisms as “...a form of pseudo-intellectual disdain for suburban life in general, with Levittown serving as its archetype.”

For example, in 1964, architect Peter Blake declared in God’sOwn Junkyardthat the suburban pattern developing in the United States is “making life there only slightly less tolerable than on tenement streets.”

He continued: “The results are palpable: children play in the street; parents spend most of their time maintaining a front garden they can’t use; the community has to maintain long roads and long utility lines to service its strung-out houses; and the suburbs go broke.” Blake also says that “America’s suburbia is now functionally, aesthetically and economically bankrupt.”

Dr. Charles Winslow, professor of public health at Yale University said that the “inferior type of small house being provided by speculative builders to meet the veterans demands [were] dollhouses that out slum the slumming is of our prewar slums...” He also said that “families living in these houses might suffer serious mental and physical ills.”

Social commentator Paul Barker describes the intensity of the criticisms, noting that “suburban” is a “sneer- word” to architects and planners.xxxvi He also says: “Those who oppose suburbia usually have highly doctrinaire views about how other people should live.” While Sieverts refers to an ideological concept of cities, Barker characterizes it as theological: “Almost all architectural and planning commentaries, in the press or in government publications, still speak of the suburban as an evil that must somehow be cast out.”

These kinds of criticisms have often been supported in the press.

Historian Joshua Ruff dismisses Lewis Mumford’s complaint that Levittown

was a “uniform environment from which escape is impossible” as “ignoring the architectural sameness (block after

block of overcrowded apartments) many new suburbanites were fleeing from in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens.”

But, despite their influence and access to the press, the retro-urbanists have been consistently ignored by households making home purchase decisions. As Barker put it, “...such critics are outnumbered many, many times by the millions for whom suburbia is a land of pleasantness, friendship and hope.”xl Moreover, the retro-urbanists did not understand the desires of suburbanizing households. As Gans put it, they came “...for a house and not a social environment.”

In the final analysis, as Journalist Edward Humes wrote: “But the veterans who snapped up these new houses were coming from a different outlook, a different place—from boarding houses and cramped apartments and lives that just a few years earlier had offered little hope of college or homeownership or lasting financial security.”

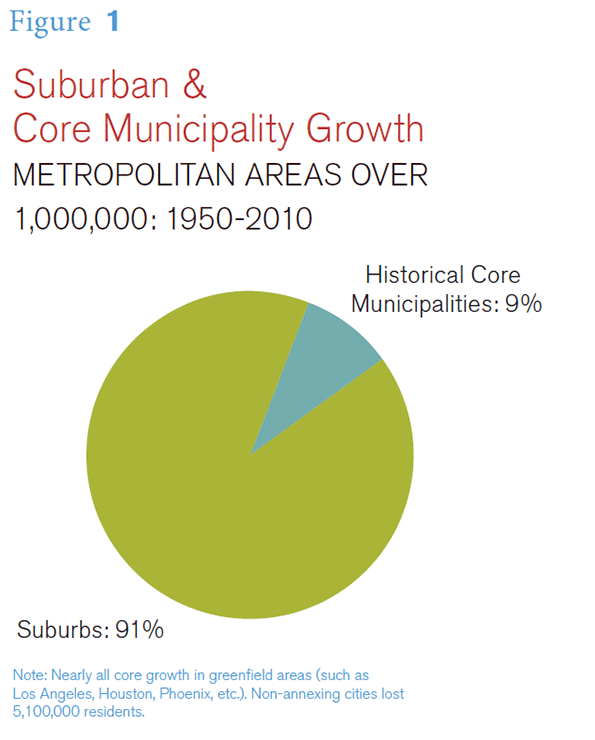

Households continued to move to the suburbs and suburbanization continued to attract nearly all population growth in the major metropolitan areas.

![]()

The Right and Wrong of Suburbanization

Ruff provides a short summary of the positive and negative perceptions with respect to Levittown (which also apply

to the great post-war suburbanization): “But Levittown was about more than just the houses. As the largest and

most influential housing development of its time, it became a postwar poster child for everything right (affordability, better standard of living) and wrong (architectural monotony, poor planning, racism) with suburbia.”

As for the “right” that Ruff refers to, it is hard to imagine more important benefits than a dispersion of wealth, affordability and a better standard of living. These are fundamental domestic public policy objectives long held by much of the nation’s leadership, including liberals. A nation of homeowners, “President Franklin D. Roosevelt believed, “of people ho own a real share in their land, is unconquerable.”

The case for the “wrong” is less clear. Architectural monotony does not negate the imperative to improve the standard of living and reduce poverty. Moreover, architectural monotony is in the eye of the beholder and clearly was of no more than secondary interest to the millions who overwhelmingly chose the suburbs. The very rowhouses that are now so widely celebrated by retro-urbanists were themselves originally stretches of identical structures with little differentiation. Planning that results in better affordability (and an improved standard of living) is good and effective, not “poor.” Finally, as noted above, the racism concern is valid, but is a more general indictment of the nation at the time and has now been moderated by a flood of minority residents to suburbia.

According to Kelly: “For all the faults attributed to them by their critics, the houses of the postwar subdivisions had widespread appeal. They may have been small and repetitious to their observers, but to their owners they represented something more than basic shelter—they were an opportunity to build a better life, a first step on the road to success. It is at that level that the housing programs of the 1940s made their greatest achievement.”

THE NEW CITY

The postwar suburbs developed because they could. History had made it possible and thus virtually inevitable.

Throughout history, people have routinely adopted new techniques and technologies that made their lives better. Nostalgia did not prevent people from abandoning outhouses for indoor plumbing or iceboxes for refrigerators. People prefer better lives and greater comfort and accept technological advance as soon as it is affordable. It is not surprising that people found better lives and comfort preferable to nostalgia and an “ideological concept of the city.”

Indeed, the city was revolutionized.

Levittown chronicler Barbara Kelly added that the postwar subdivision suburbs had “evolved into a new form of city,” while Thomas Sieverts characterized the “strange urban—rural landscape as a new form of city.”

The suburbs gradually became more independent of the core city, as employment was dispersed throughout the metropolitan area. They were no longer subordinate to the core cities, the legacy cites of the pre-war era. Jon

C. Teaford of Purdue University wrote that the term: “...‘suburb’ had become a misnomer. Economically and socially periphery is no longer a subordinate dependent of the center and thus no longer a candidate for the prefix sub[emphasis in original]” Similarly, J. John Palen of Virginia Commonwealth University wrote: “Whatever everyone thinks about suburbs, it is now indisputable that they no longer sub [emphasis in original].”

More than three decades ago, Robert Fishman of the University of Michigan suggested:

“In my view, the most important feature of the postwar American development has been the almost simultaneous decentralization of housing, industry, specialized services and office jobs; the consequent breakaway of the urban periphery from the center it no longer needs; and the creation of the decentralized environment...”

He went on to propose a new conception of the city (metropolitan area):

“The true center of this new city is not some downtown business district

but in each residential unit. From that central starting point, the members of the household create their own city from the multitude of destinations that are within suitable driving distance.”

![]()

Even “suitable commuting distance” became less of a concern for many, as Alvin Tofler’s”electronic cottage” became a reality for many as working at home expanded, facilitated by improved telecommunications. Today, in the majority of American metropolitan areas, more people work at home than take transit.

THE PLANNING RESPONSE

Long before Levittown, there were strong criticisms of the suburbs reaching back into the 19th century and even to the 17th and 18th.

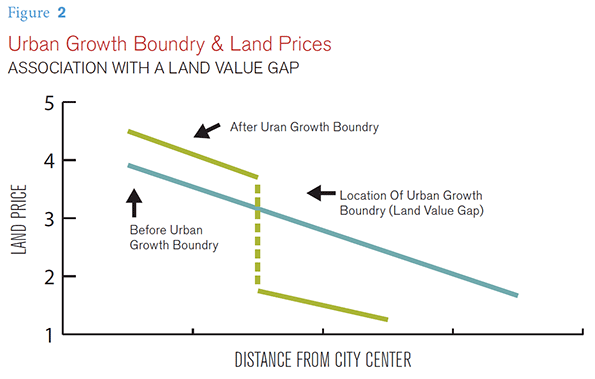

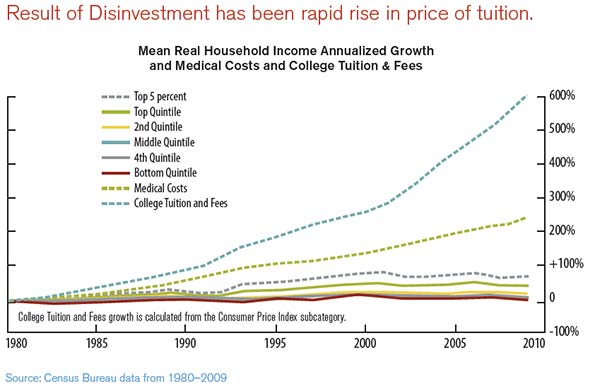

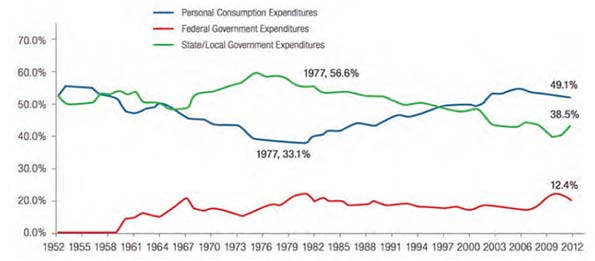

However, it took the interwar building boom to marshal political forces to implement planning restrictions intended to stop the growth of the suburbs. Under the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947, Britain’s liberal land-use policies were replaced by urban containment policies that have only become stronger over the years. Greenbelts (urban growth boundaries) were imposed around the cities of England, leaving little land for new residential development.

The result has been a severe and on- going housing crisis, with house prices having doubled or tripled compared to their pre-urban containment relationship to incomes.lv This is to be expected, since prices tend to rise where the supply

of a desired good or service (in this case land) is restricted, while demand continues unabated. Not even depressed metropolitan areas like Liverpool and Glasgow have escaped the cost escalation.

There is broad agreement among economists and even planning advocates that higher land prices occur within urban containment boundaries. lvi Planners expected that construction of higher density housing would negate the higher land price impact on house prices. Moreover, urban containment planning regimes have routinely included periodic reviews to expand land supply housing affordability. As the discussion below indicates, these approaches have failed as losses

in housing affordability have been pervasive in more restrictively regulated metropolitan areas.

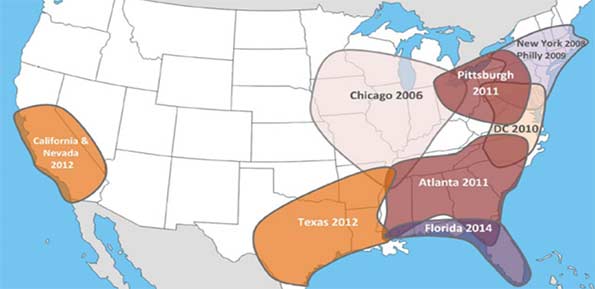

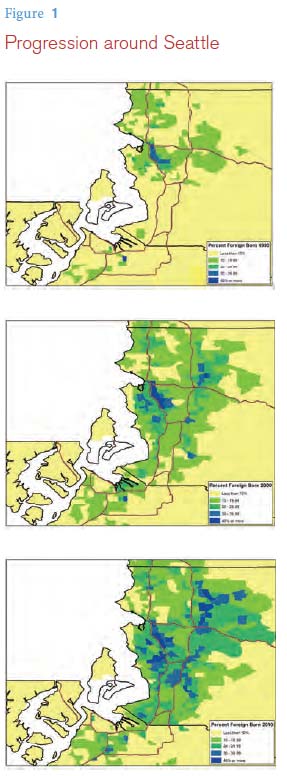

It took longer, but similar planning strategies have been adopted in many parts of the US. Their spread, however, has been slowed by America’s federal structure,lvii which did not lend itself to overnight imposition of urban containment policy. Even 70 years after World War II, the radical land use regulatory regime of the United Kingdom has been implemented in only parts of the United States.

Nonetheless, there were important adoptions of Great Britain style urban containment policy. Things began to change, especially in California and Oregon in the 1970s.

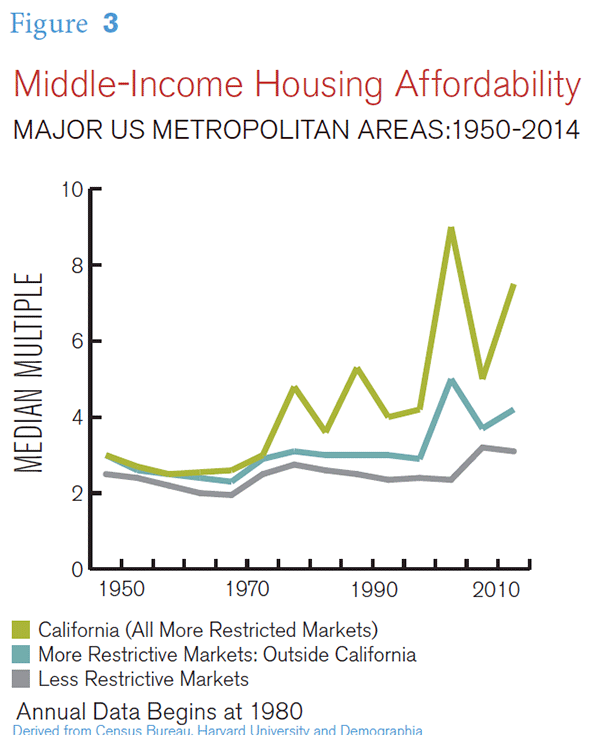

In California, restrictions were placed on the incorporation of new suburban municipalities that made it more difficult for development to extend from existing municipalities into unincorporated areas.lviii At the same time there were various environmental and land-use regulatory changes that made it more difficult to develop new housing. The net impact of this was fairly immediate house price increases relative to incomes. These housing affordability losses were recognized early some urban planning experts, such as David Dowell at University of California, Berkeleylix and Bernard Friedan at MIT.lx California’s housing affordability, which had been similar to that of the rest of the nation, began to deteriorate markedly, and by 1980 had reached unprecedented severity.

![]()

Urban containment policies were also enacted in states such as Washington, Florida, Tennessee, New Jersey and Maryland. Local initiatives significantly strengthened land use regulations, such as in the Virginia and Maryland counties of the Washington, DC-VA-MD-WV metropolitan area and the New York metropolitan area.

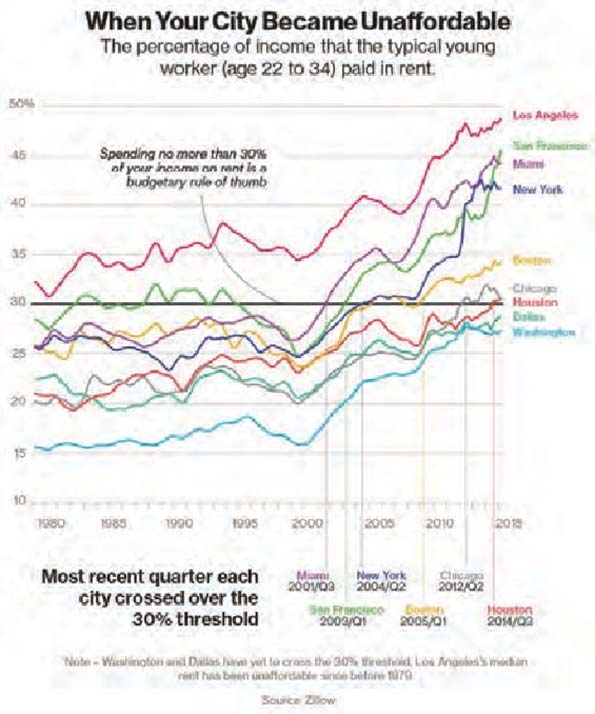

By 2000, house prices in some markets had reached five times incomes, nearly double their 1970s ratios. This is consistent with the economic principle that restricting supply tends to result in higher prices, all else equal.

The tragedy of the housing bust was to follow. Households were lured by

mortgage products that back-loaded costs so that the greatly inflated prices could seem affordable. The more restrictive land use regimes could not respond with sufficient supply to meet the increased demand. By the middle 2000’s the highest median multiples reached over 10 in the coastal California metropolitan areas, with some other metropolitan areas exceeding 5.0.

These price factors led to mortgage defaults, corporate bankruptcies, and a recession so severed that it is called the Great Recesion. It was by far the worst economic reversal since the 1930s. Through the Great Recession, the

US housing market sent ripples of economic disruption throughout the international economy.

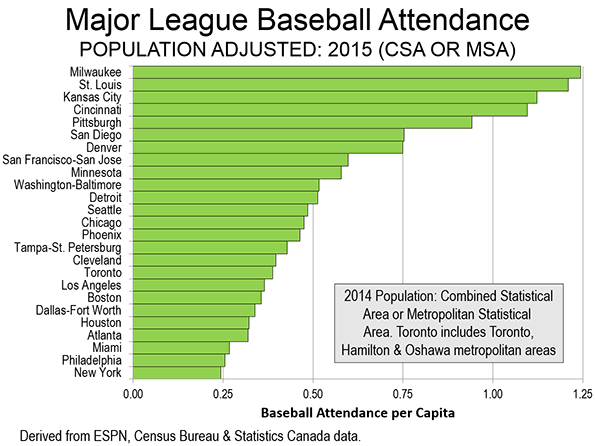

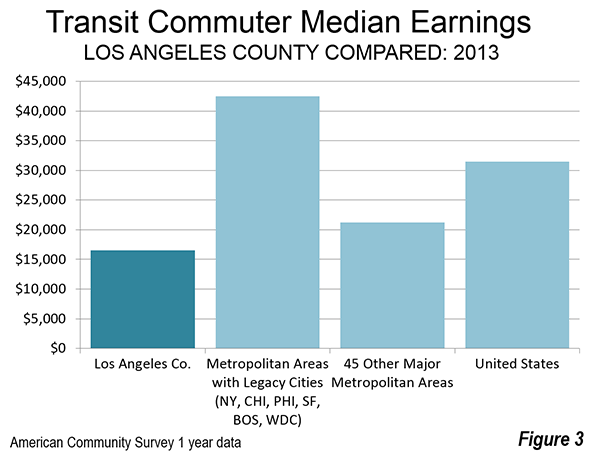

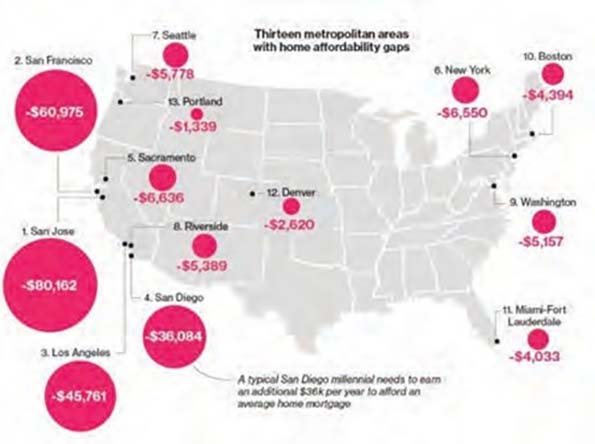

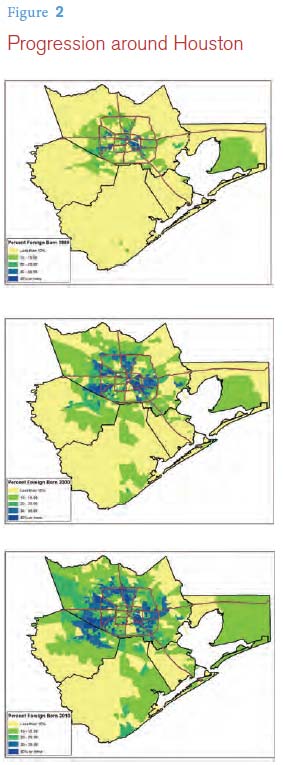

There were massive house price losses across the nation, with the largest losses where house prices had risen the most. Yet, the house price increases relative to incomes quickly resumed. By 2014, median multiples had reached 8.0 or above in the San Francisco, San Jose, San Diego and Los Angeles metropolitan areas. Housing was also severely unaffordable in the New York, Boston, Miami, Riverside-San Bernardino, and Seattle metropolitan areas and was approaching similar severity in the Denver and the Portland metropolitan areas (Figure).

![]()

The housing distortion was so great that California’s cost adjusted poverty rate became the highest in the nation, 50 percent above that of Mississippi. Despite a California Legislative Analyst’s report documenting the association between regulation and housing affordability losses, the state has continued to strengthen regulation.

Tomas Rivera Institute raised concerns about the impact of compact development on minority housing affordability:

Whether the Latino homeownership gap can be closed, or projected demand for homeownership in 2020 be met, will depend not only on the growth of incomes and availability of mortgage money, but also on

how decisively California moves to dismantle regulatory barriers that hinder the production of affordable housing. Far from helping, they are making it particularly difficult for Latino and African American households to own a home.

At the same time, throughout most of the country the historic housing affordability was preserved. Even through the housing bubble many major markets remained at or below the 3.0 housing affordability standard. There were also significant house price increases in some liberally regulated markets, but most remained at or below a 3.0 median multiple (such as Atlanta and other Less Restrictive Markets in the Figure above “Middle-Income Housing Affordability”).

Finally, even in metropolitan areas with strong policies discouraging suburban development and favoring urban core development, most growth continues the periphery. For example, in Portland more than 95 percent of that growth between 2000 and 2010 was in suburbs and exurbs. In San Francisco, 88 percent of the growth was in the suburbs and exurbs.

TOWARD A MORE ELITIST AMERICA?

The present preference in planning for urban containment policy threatens to reverse 70 years of social progress. As house prices rise relative to incomes --- a phenomenon clearly associated with of urban containment policy --- home ownership will be increasingly limited to the more affluent. Paul Barker asks why the strong land use regulations have survived. Answering his own question, he says that: “The short answer is that it protects the haves against the have-nots.” Robert Bruegmann of the University of Illinois, Chicago provides similar commentary, in chronicling the conversion of suburbs to abodes of the middle class:

“... Cities have sprawled from time immemorial and for a wide variety of reasons. As long as only a small number of the wealthiest and most powerful families occupied the most

land in the most attractive locations, there was very little sustained organized protest. Whenever a newly affluent or empowered part of the population started to enjoy this privilege, there was a backlash.”

Matthew Rognlie at the Mass- achusetts Institute of Technology has suggested that virtually all of the increased inequality identified by French economist Thomas Picketty has been in the housing sector. He suggests that:

“... the literature studying markets with high housing costs finds that these costs are driven in large part by artificial scarcity through land use regulation .... A natural first step to combat the increasing role of housing wealth would be to re-examine these regulations and expand the housing supply.

Jason Furman, Chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers called for regulatory relief in a recent address on housing affordability and the consequences of high prices on the economy.

With high house prices and further hedges against property value depreciation in local regulations, some individuals are priced out of the market entirely, and homes in highly zoned areas also become even more attractive to wealthy buyers.

Thus, in addition to constraining supply, zoning shifts demand outward, exerting further upward pressure on prices…

Worse of all, these restrictions are largely unnecessary. Better policies can secure a future for the next generation every bit as promising as the generations since World War II came to expect. The words of Presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson in 1952 are as relevant today as then: “Who shall say that the American dream is ended?”

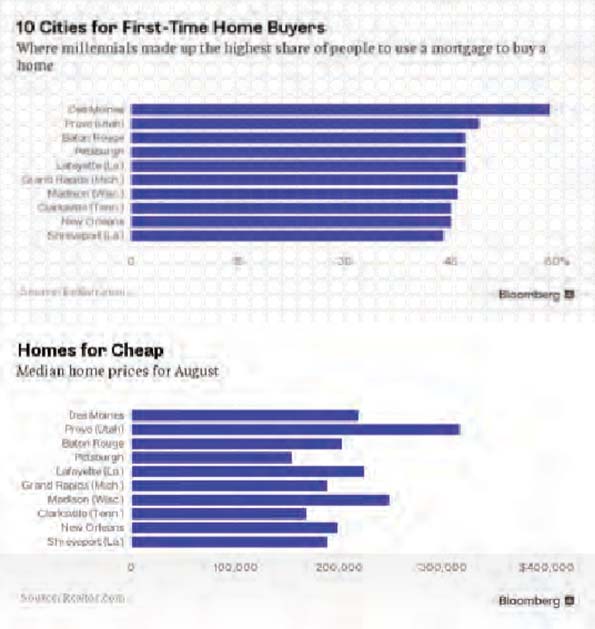

LEVITTOWNS FOR THE FUTURE

But there is a solution. Levitowns can still be built. For example, a review of four metropolitan areas shows that new, entry level detached housing can be purchased for from 2.0 to 2.5 times median household incomes in Atlanta, Columbus, Houston and Indianapolis. This is only slightly above the two times average earnings typical in Levittown, when few families had more than one wage earner. Moreover, today’s prices include a garage, and the houses are at least 50 percent larger. Implementation of recommendations in Section 9 could increase the number of new houses that replicate Levittown affordability today.

A number of policy proposals could improve the potential for improving housing affordability, particularly in the starter home market following the “trail” blazed by Levittown and other early postwar suburbs. These could restore, in the short term, the promise of Levittown for today’s threatened middle-class.

The first two relate to the stringency of metropolitan land use planning systems, since experience has demonstrated that the administration of urban containment policies not succeeded in maintaining housing affordability. Until these policies are reformed, new Levittowns are simply not likely to be built.

Recommendation #1

To retain housing affordability, liberally regulated metropolitan areas should not adopt restrictive housing

regulations, such as urban containment.

As is indicated above, urban containment policies have been virtually inextricably linked to the loss of housing affordability. The theory that the higher land prices inside an urban containment boundary will be offset by lower construction prices has proven to be entirely elusive in practice.

Recommendation #2

Wherever there is urban containment policy, it can be expected that housing affordability will further deteriorate. This approach needs to be reformed.

A road map has been provided by the Productivity Commission of New Zealand. In seeking to address the

severe housing affordability in Auckland, the Productivity Commission has recommended that greenfield land for development be opened up in greater volume once prices have become unduly distorted. As the Commission indicated: “”Where large discontinuities emerge between the price of land that can be developed for housing and land that cannot be developed, this is indicative of the inadequacy of development capacity being supplied...”

The Productivity Commission’s recommendation for an “event- driven trigger” to open more land for development also could be adopted at the state or metropolitan area level in the United States. This would require establishment of annual housing affordability targets.

Recommendation #3

Metropolitan areas with urban containment policies should consider establishing “special housing areas” outside their urban containment boundaries in order to facilitate housing that is affordable to middle income households.

These new developments could be authorized by governments to allow development of land and housing at prices similar to those, relative to incomes, that prevailed in the early suburban developments, such as Levittown. These districts should be within metropolitan areas (labor markets) and would provide advantages not only to aspiring families, but also to land owners whose land has been rendered worthless from a development perspective by urban containment policy. Limits on land prices should be set, with development proceeding only when land owners are willing to sell for prices within such limits. Generally similar proposals have been made by the New Zealand government (special housing areas), and by United Kingdom government housing researcher Kate Barker. This approach would also be similar in some respects to the successful municipal utility districts in Texas.

Recommendation #4

Governments, land developers and homebuilders should examine approaches for liberalizing regulation on starter homes, toward the end of implementing less costly delivery of housing.

Cost increasing factors such as delays in permitting, more expensive materials requirements and designs (such as favored architectural styles, including “new urbanist” designs) and other requirements that increase costs for starter homes should be reviewed. This would be appropriate in all markets and should be conducted consistent with appropriate health and safety standards. Wherever feasible, reforms should be implemented.

CONCLUSION

The legitimate purpose of planning is not so much better cities, but better lives for their inhabitants. This requires housing that is affordable and maximizes discretionary incomes and a reduction in poverty.

Planning can only be justified by the extent to which it improves people’s lives. Suburbanization, through entrepreneurship and liberal planning accomplished this, and created the Great American Middle Class after the Second World War.

As Herbert Gans suggested a half century ago:

“... whatever its imperfections, Levittown is a good place to live. Consequently, it is much less important to plan for new or improved suburban community and to make sure that more people are able to live in suburbs like those now being built. Specifically, the most urgent priority is to make the benefits of suburban living available to the poor and nonwhite families, now condemned to slum ghettos, who want to give their children

and themselves a better life beyond the city limits."

Gans further expressed concern that there needed to be a place in the suburbs for lower middle income households: lxxvi

…The ideal solution is more, better and more variegated new towns in suburbs, but the first priority in the years to come is more communities for the less affluent.”

Wendell Cox is Chair, Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California) and principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

![]()

, a collection of historical travel essays, and

, a collection of historical travel essays, and