No industry generates more hype, and hope, than technology. From 2004 to 2014, the number of tech-related jobs in the United States expanded 31%, faster than other high-growth sectors like health care and business services. In the wider category of STEM-related jobs (science, technology, engineering and mathematics), employment grew 11.4% over the same period, compared to 4.5% for other jobs. The Commerce Department projects that growth in STEM employment will continue to outpace the rest of the economy through 2018.

But all the new tech jobs have not been evenly distributed across the country. To determine which areas are benefiting the most from the current tech boom, Mark Schill, research director at Praxis Strategy Group, analyzed employment data from the nation’s 52 largest metropolitan statistical areas from 2004 to 2014. He looked at the change in employment over that timespan in companies in industries we associate with technology, such as software, engineering and computer programming services. (Note that this includes everyone at these companies, such as non-tech employees like janitors and receptionists). He also looked at the change in the numbers of workers in other industries who are classified as having STEM occupations (science, technology, engineering and mathematics-related jobs). This captures the many tech workers who are employed in businesses that at first glance may not seem to have anything to do with technology at all. For instance just 7% of the nation’s 1.5 million software developers and programmers work at software firms — the vast majority are employed in industries as disparate as manufacturing, finance, and business services.

Our list features some well-known outperformers, but also some surprising metro areas usually not associated with venture capital and Silicon Valley. We also found that some high-profile metro areas that like to tout themselves as the “next Silicon Valley” are actually at best the middle of the pack in terms of tech and STEM job growth.

The Strongest Engines

At the top of our list is a group of cities that have long been identified with tech growth. Our No. 1 city, Austin, Texas, boasts the strongest expansion in tech sector employment of any of the nation’s 52 largest metropolitan areas from 2004 to 2014, 73.9%, as well as 36.4% growth in STEM jobs, the fourth-highest growth rate in the country. Coming in a close second is Raleigh, N.C., part of the renowned Research Triangle region, home to outposts of multinationals like Bayer, BASF, GlaxoSmithKline, IBM and Cisco. The Raleigh metro area posted a 39% increase in STEM jobs from 2004-14, the fastest growth in the nation, albeit from a smaller base than many of the other biggest metro areas.

However, the Bay Area continues to reign as the tech center with the most momentum. San Jose, which covers most of Silicon Valley, ranks third with 70.2% growth in tech sector employment since 2004 and a hefty 25.8% increase in STEM employment. The San Francisco metro area, which includes San Mateo to the south, ranks fifth with a 67.4% jump in tech industry employment as well as a STEM jobs increase of 27.5%.

There may be more tech industry employees and workers in STEM occupations in the New York City, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles metro areas, but San Jose has the strongest concentration of tech horsepower in the nation, with by far the highest per capita concentration of people in engineering professions. San Jose’s tech industry is responsible for 14.1% of all jobs, almost five times the national average of 2.9%. The share of STEM workers is 15.5% of its total workforce, three times the 5.0% proportion in the overall U.S. population. Both figures are easily the highest in the nation. San Francisco clocks in at second nationally with 7.6% of its jobs in tech industries and is fifth in STEM representation, at 8.7% of all workers, behind San Jose, the nation’s capital, Seattle, and our No. 1 city, Austin.

Silicon Valley’s thick concentration of titans like Intel, Apple, Oracle, Google and Facebook has created an innovative ecosystem, which, as Pando Daily’s Michael Carney describes, supports a “systematic irrationality and a feedback loop” that encourages many tech entrepreneurs to turn down the easy early exit of selling out to a bigger company and make the commitment to grind for a decade or more in the hopes of joining the afore-mentioned standouts as a massive success.

No other area apart from Seattle (No. 7 on our list) comes close in this regard to nurturing tech giants. The success of the Bay Area and Valley also attracts outsiders who want to be close to the action, including foreign players like Samsung, and old economy stalwarts that need a tech infusion like Wal-Mart.

The Surprise Tech Upstarts

Some of the others in our top 10 are not as renowned as tech centers, but have experienced rapid growth over the past decade. The biggest surprise may be No. 4 Houston, which enjoyed a 42.3% expansion of jobs in tech industries and a big 37.8% boost in STEM jobs from 2004-14. Much of the growth was in the now sputtering energy industry, but also medical-related technology, which continues to grow rapidly. Houston is the home to the Texas Medical Center, the world’s largest concentration of medical facilities. It also ranks second to San Jose in engineers per capita.

The Mountain West metropolises of Salt Lake City (sixth) and Denver (11th) also have posted impressive growth, and now boast considerably higher share of tech and STEM workers in their populations than the national average; in Salt Lake City 5.9 percent of jobs are in tech industries and 4.1% are in STEM. Denver is even more impressive with 7.3% of jobs in tech industries and 5.1% working in STEM. Salt Lake City’s gains are linked to a continued migration of tech firms, largely from Silicon Valley, whereas Denver is making waves as a start-up incubator.

The other top cities on our growth list all tend to be emerging tech centers. These include No. 8 Nashville, where strong growth in data centers and systems design firms is at least partially tied to its strength in the health sector, No. 9 Jacksonville, driven by IT and computer programming services firms, and, perhaps most surprising, No. 10 Memphis, whose 35% tech growth since 2012 is due mostly to significant recent growth in engineering services. However, the tech sectors in these cities are still very small — Memphis had only 7,800 tech industry workers last year — and all three still trail the national average for the share of tech workers in the population.

More Hat Than Cattle?

Some journalists and pundits believe tech is moving from its suburban roots and towards dense, large cities. And there’s some truth to the fact that the social media boom, and some tech-driven services, appeal naturally to the same creative and culturally minded workforce concentrated in core cities. But this shift is not too evident in terms of job creation. High-tech growth in city centers may have more to do with tech sector expansion in general occurring in every type of geography.

Suburban Silicon Valley, for example, has nearly twice the concentration of tech jobs as San Francisco; even amidst the social media boom, the Valley since 2012 has greatly outpaced the City and its immediate suburbs in terms of both new tech and STEM employment. The largest tech projects going up in the Bay Area — new headquarters for Google, LinkedIn and Apple – are being built in the Valley, not the city.

Unlike San Francisco, cities located far from tech centers have not done nearly as well as often reported. Chicago has been desperate to portray itself as a major tech center, developing elaborate facilities for companies, while promoting its own high-tech icon, Groupon, and crowing over the high-profile names its lured to open up offices in the city, like Google. Mayor Rahm Emmanuel has even proposed expanded bike lanes as part of his plan to lure tech-savvy members of the “creative class” to his city.

Yet despite all the noise, Chicago ranked a mediocre 33rd on our growth list, with 20.3% tech industry employment growth from 2004-14 and a mere 3.8% growth in STEM jobs. Both numbers are below the national average, as is the region’s percentage of employees in tech and STEM.

How about Los Angeles, with its fabulous weather, elite universities (Caltech, University of Southern California, UCLA, Cal Poly Pomona and Harvey Mudd College) and close ties to the creative engine of Hollywood? Local boosters like to claim that the metro area is undergoing a full-scale “tech boom” focused on the west side in its so-called “Silicon Beach.” To be sure, the region still boasts the second largest pool of STEM workers in the country, in part due to its legacy of manufacturing, led by its shrunken but still sizable aerospace industry (63,000 jobs, down by 90,000 since the end of the Cold War). But Los Angeles’ large STEM numbers are to a great degree a function of the massive population of the metro area – the percentage of STEM employees in the workforce is 4.9%, a hair below the national average of 5%, while 2.5% of its workforce is in tech industries, trailing the national average of 2.9%. Los Angeles lands a poor 38th on our growth list, with an 18.7% expansion in tech industry jobs since 2004 and a 4% increase in STEM jobs, a shade below the national average of 4.2%.

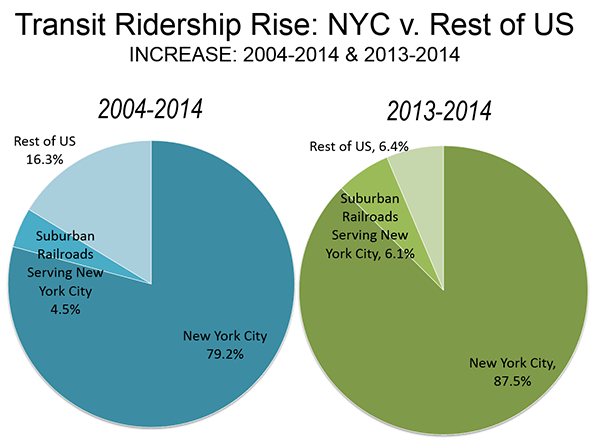

But perhaps the biggest surprise is New York, whose boosters are now claiming it to be the No. 2 tech center in the nation and the Valley’s chief rival. However, on our job growth list New York sits in a mediocre 35th place, with 24.3% growth in tech industry employment over the past 10 years, and only 4% in the last two. In STEM, New York still has the largest number of jobs of any metro area in the nation at 428,000 as of 2014, but that’s up a paltry 2.7% since 2004, and, as in the case of L.A., is a function of its large population. The percentage of STEM employees in the local workforce falls short of the national average at 4.4%. New York has gained about 51,000 technology industry jobs since 2004 and 12,000 since 2012, giving it a total of roughly 265,000 tech jobs. But that’s some 70,000 fewer than the Bay Area, an economy about one third the size of New York’s.

Critically, most New York “tech” seems more linked to media than actual physical products, essentially replacing many of its old media jobs with newer ones. Part of the problem for New York is that it’s profoundly weak in engineering talent, ranking 78th out of 85 metropolitan areas in engineers per capita.

The Bay Area Versus The Rest

The current social media bubble will surely pop, but as Michael S. Malone and others have noted, the Bay Area’s preeminence will likely continue, fueled by its unique concentration of engineers, entrepreneurs, and risk capital. Instead of losing out to New York, Silicon Valley and San Francisco are luring many top performers from Wall Street. Google alone has 1,200 employees who formerly worked for large U.S. investment banks, and migration from the Big Apple to California is now at its highest level since 2006.

In the coming years the engineering-centered Valley seems better positioned to seize on the challenges posed by the “Internet of things,” including systems for heating and cooling and autonomous cars, as well as biotechnology. In the long run, the Valley’s hegemony is threatened not by any one place, but by several that offer significant technical expertise, with far lower housing costs. San Francisco is already by far the nation’s least affordable metro area. Only 11% of residents making the median annual income can afford to buy a home, according to the NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Opportunity Index – and the median income is in the San Francisco area is a hefty $100,400. The Valley is not far behind at 21.8%. The high prices throughout the Bay Area has become a concern of tech executives, who fear they will have troubles attracting more experienced engineers and managers.

No matter the headlines, the reality is that future tech growth is more likely to be created by the less sexy business services sectors than by Internet media or software publishers. In the last decade three often-ignored industries — engineering services, systems design and custom programming – added nearly 750,000 jobs, while software providers and Internet properties added less than 200,000. The decentralizing force of these boring sectors is what’s driving growth in the second- and third-tier tech cities.

But despite these trends, don’t expect the landscape of American technology, particularly at the high end, to change dramatically in the near future. Inertia is a powerful force, as is the enormous concentration of venture funds and expertise around the Bay Area. But if no one area can hope to challenge Silicon Valley’s lead position, it is likely tech growth will continue to flow to other areas that could collectively take the tech capital of the world down a notch or two.

| 2015 Metropolitan Tech-STEM Growth Index |

| Rank | Region (MSA) | Score | 2004-2014 Tech Industry Growth | 2012-2014 Tech Industry Growth | 2014 Tech Industry LQ | 2004-2014 STEM Occuptn Growth | 2012-2014 STEM Occuptn Growth | 2014 STEM Occuptn LQ |

| 1 | Austin | 87.4 | 73.9% | 21.8% | 1.90 | 36.4% | 11.2% | 1.77 |

| 2 | Raleigh, NC | 85.7 | 62.3% | 17.0% | 2.23 | 39.0% | 13.4% | 1.63 |

| 3 | San Jose | 78.1 | 70.2% | 19.6% | 4.92 | 25.8% | 10.2% | 3.11 |

| 4 | Houston | 77.8 | 42.3% | 18.5% | 1.26 | 37.8% | 12.3% | 1.30 |

| 5 | San Francisco | 70.5 | 67.4% | 13.0% | 2.64 | 27.5% | 7.9% | 1.74 |

| 6 | Salt Lake City, UT | 70.0 | 62.4% | 11.0% | 1.44 | 33.3% | 7.5% | 1.17 |

| 7 | Seattle | 66.5 | 58.3% | 7.4% | 2.34 | 37.6% | 6.2% | 1.94 |

| 8 | Nashville | 65.3 | 68.6% | 15.1% | 0.68 | 14.7% | 7.6% | 0.80 |

| 9 | Jacksonville, FL | 62.7 | 58.4% | 13.5% | 0.87 | 16.0% | 8.2% | 0.84 |

| 10 | Memphis, TN | 61.0 | 35.3% | 34.9% | 0.41 | 5.0% | 7.4% | 0.63 |

| 11 | Denver | 56.4 | 34.5% | 10.1% | 1.79 | 24.4% | 7.8% | 1.47 |

| 12 | Indianapolis | 55.9 | 52.2% | 8.2% | 0.88 | 15.0% | 7.4% | 1.04 |

| 13 | Charlotte, NC | 54.8 | 36.4% | 8.7% | 0.81 | 23.8% | 7.1% | 0.96 |

| 14 | Phoenix | 54.1 | 51.1% | 13.3% | 0.90 | 13.9% | 5.1% | 1.10 |

| 15 | Kansas City, MO | 54.0 | 46.2% | 11.2% | 1.49 | 16.5% | 6.0% | 1.11 |

| 16 | Portland, OR | 52.5 | 33.2% | 9.6% | 1.10 | 19.8% | 7.2% | 1.31 |

| 17 | San Antonio | 52.1 | 43.5% | 4.3% | 0.92 | 26.6% | 4.8% | 0.82 |

| 18 | Dallas | 52.1 | 43.9% | 6.0% | 1.11 | 22.0% | 5.4% | 1.20 |

| 19 | Boston, MA | 50.9 | 43.4% | 9.9% | 2.28 | 16.0% | 5.2% | 1.59 |

| 20 | Sacramento | 47.5 | 47.8% | 6.7% | 0.94 | 11.6% | 4.7% | 1.36 |

| 21 | Grand Rapids | 46.7 | 26.4% | 13.2% | 0.50 | 7.1% | 7.6% | 0.95 |

| 22 | Louisville, KY | 46.5 | 23.7% | 10.8% | 0.57 | 16.4% | 6.0% | 0.74 |

| 23 | San Diego | 45.4 | 33.8% | 7.2% | 1.81 | 16.0% | 4.7% | 1.44 |

| 24 | Las Vegas | 45.1 | 13.6% | 15.0% | 0.57 | 8.8% | 8.0% | 0.47 |

| 25 | Tampa | 43.7 | 26.8% | 10.7% | 0.99 | 4.2% | 7.4% | 0.91 |

| 26 | Orlando | 42.9 | 18.3% | 8.7% | 0.96 | 13.9% | 6.4% | 0.82 |

| 27 | Baltimore | 40.0 | 30.4% | 5.2% | 1.55 | 16.6% | 2.6% | 1.42 |

| 28 | Atlanta | 38.0 | 19.1% | 5.7% | 1.22 | 10.2% | 5.4% | 1.10 |

| 29 | Minneapolis | 37.8 | 17.8% | 7.7% | 1.07 | 11.0% | 4.6% | 1.24 |

| 30 | Cincinnati, OH | 37.0 | 20.6% | 8.7% | 0.81 | 8.1% | 4.0% | 1.04 |

| 31 | Pittsburgh, PA | 35.8 | 25.2% | 3.1% | 1.06 | 14.4% | 2.5% | 1.06 |

| 32 | Miami | 35.0 | 3.6% | 13.3% | 0.64 | -1.0% | 7.3% | 0.62 |

| 33 | Chicago, IL | 34.3 | 20.3% | 8.8% | 0.91 | 3.7% | 3.8% | 0.93 |

| 34 | Richmond, VA | 32.4 | 33.9% | -2.9% | 0.79 | 9.7% | 2.2% | 1.00 |

| 35 | New York | 32.2 | 24.3% | 4.7% | 0.96 | 5.0% | 2.7% | 0.89 |

| 36 | Cleveland | 32.1 | 21.7% | 5.3% | 0.74 | 4.1% | 3.2% | 0.91 |

| 37 | Hartford | 31.9 | 30.7% | 4.9% | 0.89 | 4.9% | 1.2% | 1.12 |

| 38 | Los Angeles | 31.1 | 18.7% | 4.9% | 0.86 | 2.1% | 4.0% | 0.99 |

| 39 | Detroit | 29.2 | 6.2% | 8.5% | 1.97 | -2.3% | 5.4% | 1.44 |

| 40 | Columbus, OH | 27.9 | 9.5% | 3.1% | 1.07 | 9.4% | 2.3% | 1.19 |

| 41 | Riverside | 25.5 | 12.8% | 0.1% | 0.33 | 4.7% | 2.7% | 0.53 |

| 42 | Providence | 24.9 | 13.1% | 1.3% | 0.76 | 0.5% | 3.1% | 0.88 |

| 43 | New Orleans | 24.8 | 21.6% | 8.0% | 0.68 | -11.1% | 2.4% | 0.68 |

| 44 | Oklahoma City, OK | 23.9 | 0.4% | -4.8% | 0.49 | 15.5% | 2.6% | 0.96 |

| 45 | Buffalo | 23.2 | 26.3% | -2.4% | 0.80 | 3.1% | -0.1% | 0.85 |

| 46 | Birmingham | 22.7 | 3.3% | 2.7% | 0.65 | 1.7% | 2.8% | 0.82 |

| 47 | St. Louis, MO | 21.9 | 9.5% | -3.5% | 0.89 | 3.1% | 2.9% | 1.00 |

| 48 | Philadelphia, PA | 21.6 | 10.0% | 2.4% | 1.17 | 0.6% | 1.2% | 1.09 |

| 49 | Rochester, NY | 19.9 | 12.0% | 8.1% | 0.74 | -4.5% | -0.8% | 1.06 |

| 50 | Washington, DC | 16.4 | 7.3% | -4.7% | 2.59 | 10.8% | -2.0% | 2.07 |

| 51 | Milwaukee | 16.3 | 0.1% | -2.8% | 0.76 | 1.5% | 1.6% | 0.99 |

| 52 | Virginia Beach | 8.0 | -2.2% | -7.3% | 1.04 | 1.5% | -1.5% | 1.05 |

To determine the metro areas that are generating the most tech jobs, Mark Schill of Praxis Strategy Group, mark@praxissg.com, examined employment data in two different categories. Half our ranking is based on changes in employment at companies in high-technology industries, such as software and engineering. (This includes all workers at these companies, some of whom, like janitors or receptionists, do not perform tech functions). Half is based on changes in the number of workers classified as being in STEM occupations, which captures tech workers who are employed in all industries, including those not primarily associated with technology, such as finance or business services. We ranked the 52 largest U.S. metropolitan statistical areas by the growth in tech and STEM employment from 2004 to 2014, as well as for their more near-term growth from 2012 to 2014 to give credit for current momentum.

This piece originally appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is also executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is also author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Mark Schill is a community process consultant, economic strategist, and public policy researcher with Praxis Strategy Group.

Photo "Sixth Street Austin" by Larry D. Moore. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

![]()

and

and