In 2009, the two richest men in America organized a confidential dinner meeting of billionaires in New York City, hosted by David Rockefeller. Guests included George Soros, Michael Bloomberg, Ted Turner, and Oprah Winfrey. The topic of discussion was philanthropy. Each billionaire was asked to describe his philosophy of giving. CNN-founder Ted Turner told the story tale of how he had made a spur-of-the-moment decision to donate $1 billion, most of his future, to the United Nations. During this dinner, Bill Gates and Warren Buffet started the biggest fundraising drive in history. Setting examples though their own charity, Gates and Buffet initiated “The Giving Pledge”, a campaign encouraging billionaires to commit the majority of their wealth to philanthropic causes. So far around 113 billionaires have agreed to the pledge.

Billionaires are targeted because Gates and Buffet believe that only they have sufficient funds to make a dent into the world’s major problems. The United States was initially chosen in part because the nation has a stronger culture of donating. The social contract in the United States puts stronger emphasize on giving back something to society by those fortunate enough to have acquired wealth. Bill Gates has already donated close to $30 billion dollars of his own wealth. He has further pledged to donate his remaining wealth of about $60 billion (leaving his three children $10 million each). Omaha billionaire Warren Buffett was inspired by his friend Gates’ example and also pledged all of wealth to charity. Leaving only a small endowment to his children, Buffet stating “I want to give my kids just enough so that they would feel that they could do anything, but not so much that they would feel like doing nothing”.

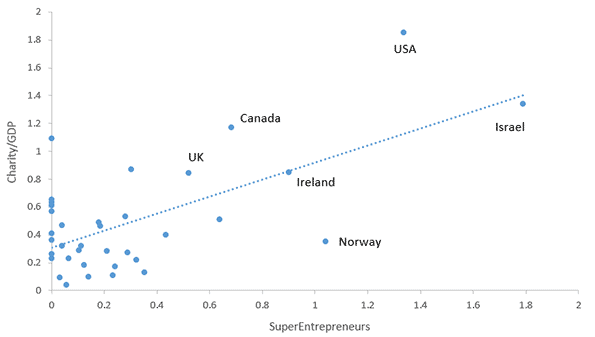

On average, the wealthy in the United States tend to donate a higher share of assets to charity than those in other countries. There also appears to exist an international correlation between charitable donations and billionaire entrepreneurship. The Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project cites data about cross-country differences in charitable donations. The 2004 book “Global Civil Society: Dimensions of the Nonprofit Sector” contains charitable donations as a share of GDP in 36 countries. According to this source Americans donated 1.9% of GDP to charity, compared to 0.3% of GDP in continental Europe.

In the publication “SuperEntrepreneurs – and how your country can get them” we recently examined the circa 1000 self-made men and women who have earned at least $1 billion dollars and who have appeared in Forbes magazine’s list of the world’s richest people between 1996 and 2010. There is a very strong correlation between the per capita number of SuperEntreprenures in different countries and donations to charity as a share of GDP. This relationship holds also when controlling for per capita GDP and tax rates. Other than the United States, countries with a high count of SuperEntreprenures and high charity as a share of GDP includes Israel (1.3 percent of GDP), Canada (1.2 percent) and the United Kingdom (0.8 percent). Several British Superentreprenurs have joined the Gates and Buffet Giving Pledge to donate half their wealth to charity, including Michael Anthony and Richard Branson.

It may be that the strong correlation between charity and the number of SuperEntreprenurs is not causal and reflects cultural differences, such as Anglo-Saxon countries donating more to charity and having more entrepreneurship. To some extent, there may be an interplay between Anglo-Saxon capitalist culture and Anglo-Saxon prescription for charity, especially for the fortunate. Tocqueville has argued that Protestant norms such as industry, frugality, charity and humility were important for American development. The Calvinist Puritan settlers brought with them strong norms of charity from England, which also influenced Canada and Australia. Interestingly, a similar norm towards expectations of charity from the wealthy exists in Jewish culture, which may in part account for the high rate of charity in Israel. The lower rates of charitable giving is found in poorer countries such as Mexico (0.04 percent of GDP) and India (0.09 percent) but also in Germany (0.13 percent) Austria (0.17 percent), Korea (0.18 percent) and Japan (0.22 percent).

American capitalism differs from other societies in its historical focus on both the creation of wealth and the reconstitution of wealth through philanthropy. In 1957, Historician Merle Curti argued that “philanthropy has been one of the major aspects of and keys to American social and cultural development”. The implicit social contract allows rich Americans to retain most of their wealth from taxation. In return, they voluntarily give much of it back to society, in projects of their choosing. The notion exists that wealth beyond a certain point should be invested back in society to expand opportunity for future generations. In this way John D. Rockefeller, the richest man in American history, gave back 95 percent of his wealth before he died.

The legitimacy of American capitalism has in part been upheld through voluntary donations from the rich. Social norms regulating donations differ markedly between Europe and the United States, not only for the rich. In the United States, around 2 percent of GDP is donated to charity each year; about ten times higher the ratio of European countries. Based on tax data, Fortune Magazine estimates that the 400 highest earning Americans donate $15 billion to charity each year, or around ten percent of their annual income. Compared to other donors, wealthy Americans are more likely to donate to education and the arts but less likely to donate to religion.

Much of the new wealth created historically has thus been given back to society. This has had several feed-back effects on capitalism. For one, the practice has limited the rise of new dynasties. Another positive feed-back mechanism is that the donations to research and higher education in particular has allowed new generations to become wealthy. In his lifetime, Rockefeller alone established many important institutions, including the University of Chicago, Spelman College, The General Education Board, National Bureau of Economic Research, Brookings Institution, and the Rockefeller Foundation. The University of Chicago is not the only great private research universities created through individual philanthropy. The same is true for Stanford, MIT, Johns Hopkins, Carnegie-Mellon, and Duke.

Lastly the practice of philanthropy creates legitimacy for capitalism among the public. Bill Gates, the richest man in America, accumulated his wealth using famously sharp elbows. Yet his is one of the most popular people in the country. In one public Pew poll, he was viewed favorably by 69 percent and unfavorably by only 15 percent of the public, the best numbers of any public person polled. Similarly according to Gallup Bill Gates in the most admired man in America who is not a current or former President.

Scholars Asc and Phillips have disused the “entrepreneurship-philanthropy nexus” at length, arguing that “[m]uch of the new wealth created historically has been given back to the community, to build up the great social institutions that have a positive feedback on future economic growth.” Asc and Phillips describe the importance of these norms in American economic history: “For Carnegie, the question was not only, ‘How to gain wealth?’ but, importantly, ‘What to do with it?’ The Gospel of Wealth suggested that millionaires, instead of bequeathing vast fortunes to heirs or making benevolent grants by will, should administer their wealth as a public trust during life”. Charitable instincts amongst highly successful entrepreneurs is relevant for economic development, in a time where there is global concern that rich dynasties will dominate capital ownership by investing inherited wealth. The combination of opportunities to create new wealth and philanthropy has so far ensured that Anglo-Saxon societies are characterized by new wealth, compared to countries such as France where inherited wealth plays an increasingly important part in the economy.

Dr. Nima sanandaji is a frequent writer for the New Geography. Dr. Tino Sanandaji is a full-time researcher at the Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IFN) in Stockholm. They have co-authored “SuperEntrepreneurs – and how your country can get them” (Center for Policy Studies) which has received considerable media impact during recent weeks.

Bill Gates photo by PauloHenrique.

Acs, Z.J., and R.J. Phillips (2002). “Entrepreneurship and philanthropy in American capitalism”. Small Business Economics, 19;3:189-204.

Curti, M. (1957). "The History of American Philantropy as a Field of Research", The American Historical Review, 62;2:352-363. De Tocqueville, A. (1966), reprint from original 1835 publication. “Democracy in America”, New York, NY: HarperCollings.

Fortune Magazine and CNN Money (2010). "The $600 billion challenge", 2010-06-16. Blog post availiable on http://features.blogs.fortune.cnn.com/2010/06/16/gates-buffett-600-billion-dollar-philanthropy-challenge/ when last checked 2013-12-31.

Lester, S., W. Sokolowski and Associates (2004). “Global Civil Society: Dimensions of the Nonprofit Sector, Volume Two”, Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press.

a collection of historical travel essays. His new book,

a collection of historical travel essays. His new book,