Obviously states aren’t going anywhere anytime soon, but a number of folks have suggested that state’s aren’t just obsolete, they are downright pernicious in their effects on local economies.

One principal exponent of this point of view is Richard Longworth, who has written about it extensively in his book “Caught in the Middle” and elsewhere. Here’s what he has to say on the topic:

In the global era, states are simply too weak and too divided to provide for the welfare of their citizens…The reason is a deep, intractable problem. Midwestern states make no sense as units of government. Most Midwestern states don’t really hang together – politically, economically, or socially. In truth, these states and their governments are incompetent to deal with twenty-first century problems because of their history, rooted in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Longworth expounds upon this to identify a series of specific issues, which I’ll put into my own terms.

1. States do not represent communities of interest. With some exceptions, states consist of cities, rural areas, and regions that have very distinct histories, geographies, economies, and and event cultures. As a result, it is incredibly difficult for legislators and leaders from various parts of the state to find common cause.

Here’s how Longworth describes Illinois:

Illinois, like Indiana, is three states, and for the same reasons. The southern third, again south of I-70, is a satellite of the South – more give to conservative religions, gun racks in pickup trucks, and a deeply conservative Republicanism….Most of the rest of the state is called Downstate to differentiate it from Chicago, even though some of it, such as Rockford, is actually north of the city. It is an unfocused place…what unites this heterogeneous region is a dislike of the third region, Chicago. Chicago dominates Illinois – politically and economically…If the rest of Illinois obsesses about Chicago, Chicago gives the impression – an accurate one, in fact – of never thinking about the rest of Illinois.

Additionally, I might add my observation that this creates a situation where the policies which are right for one area may be wrong for another. Since it is the nature of governments to promote uniform rules, this often leaves one or even all regions of a state with suboptimal rules. In fairness, there are are often some types of flexibility, such as that provided by different classes of cities. But important macro policies remain one size fits all.

Consider Illinois. It’s a combination of a global city core in Chicago, a Rust Belt hinterland, and a southern fringe region. State policy is set by the Chicago elite as a general rule, and predictably it follows a big city, global city favorable model: strong home rule powers for large municipalities, a high tax/high service type model, strong public sector unions, etc. This pretty much works for Chicago, but for downstate it puts their communities in a major economic vice since they don’t benefit from global city friendly policies and are competing against other places that have optimized in other ways.

Indiana being one example. It is pretty much the opposite. Its largest city region is only about 25% of the state’s population, meaning Indiana is dominated by rural and small city constituencies. As a result, Indiana has optimized for a “Wal-Mart” strategy such as through its low-service/low-tax approach, weak environmental rules, and very weak (I’d argue nearly non-existent) home rule powers for even its largest municipalities. This is great if you are a small manufacturing city trying to beat out Ohio, Michigan, and Illinois for low wage manufacturing and distribution jobs (which sounds bad but is realistically the best short term play these places have). But it’s pretty terrible if you are Indianapolis and trying to fight to have a place in the global economy, attract choice talent, build biotech and high tech business clusters, etc.

2. Arbitrary state lines encourage senseless border wars. With limited exceptions, the major cities of the Midwest (and often elsewhere around the country) were founded on major bodies of water like rivers, lakes, or an ocean. These were often boundaries of states, thus major cities are frequently at the edge, not the center of states. This means not infrequently you find multi-state metro areas, which creates structural conflicts of interest. The logical economic unit is the metro area, but it matters from a local fiscal point of view (i.e., the ability to collect income, sales, and property taxes) where particular businesses locate. Thus we frequently see the case where localities spend tons of money on incentives simply to get businesses to relocate within the same metro area. You can have bidding wars without multiple states (such as neighboring suburbs competing over a Wal-Mart), but these seldom involve major state level incentives.

Longworth again summed this up masterfully in a recent blog post called “The Wars Between the States” where he documents the incentives being doled out to convince companies to move back and forth across the state border in the Kansas City metro area:

It would seem impossible for Midwestern states to get any sillier and more irrelevant, but they’re trying. In a time of continuing recession and joblessness, with crunching budget problems, failing schools, crumbling infrastructure and no real future in sight, these states have decided to solve their problems by stealing jobs from each other.

The most recent example is the so-called “border war” between Kansas and Missouri, as the two states compete to see how much money they can throw at businesses to move from one state to the other. The focus of this war is Kansas City — both the Kansas one and the Missouri one, basically a single urban area divided not only by an invisible line down the middle of a street but by a mindless hostility that keeps its two parts from working together.

…

Competition with “Europe, India, China and the rest of the world” has nothing to do with this juvenile job-raiding. In fact, this “border war” keeps Missouri and Kansas from competing globally — indeed, robs them of the tools they need to compete globally. Some rational thought shows why. It’s precisely these states’ inability to compete globally that causes them to declare war on the folks next door. In a global economy, Kansas and Missouri aren’t competing with each other, any more than Illinois, Indiana and Wisconsin are competing with each other. The real competition is 10,000 miles away and all Midwesterners know that we’re losing it.

[ Update 5/5/2014: It looks like Missouri and Kansas may be about to declare a truce in their border war ]

3. Many state capitals are small, isolated, and cut off from knowledge about the global 21st century economy. In some states the state capital is a large city that is well-connected to the global economy – Atlanta, Indianapolis, St. Paul, and Nashville come to mind. But often state capitals were selected because they were in the geographic center of the state, not because they were major centers in their own right. Some, like Indianapolis, managed to grow into major cities. But many others did not. Think Springfield, Jefferson City, Frankfort, etc. This means that the state capital of many states is not very large, and often not very plugged into the global conversation. Longworth again captures the implications of this:

There is another reason why state governments are botching the economic needs of their states. Some 150 to 200 years ago, state capitals were picked not for economic reasons, but for geographic ones. Many of them remain in this isolated irrelevance today, far from the real action of any of the territories they are meant to govern…In this era of globalization, with overnight shipping and instant communications, this shouldn’t make any difference. In fact, it does. Global cities such as Chicago depend on face-to-face contact, and isolated state capitals live out of earshot of this conversation. The winds of globalization are transforming state economies and generating new thinking about state futures, but the news takes a long time to get to the state houses and legislatures.

4. Metro areas are the engines of the modern economy, but the rules for municipal and regional governance are set by states, and often in a manner that is directly contrary to urban interests. In this Longworth channels the Brookings Institution, which has tirelessly documented the importance of metro area economies to the nation as well as all the ways states, frequently controlled by non-urban legislators who are actively fearful of cities, have often imposed enormous burdens on those metro areas by tying them down with a morass of Lilliputian rules. Again Longworth:

States set the boundaries of urban jurisdictions and decide whether or how they can merge. They tell cities who they can tax and how, whether this helps cities or not. State governments help finance local infrastructure and dictate, from miles away, how that money is spent. State priorities on education and workforce programs leave city residents incompetent to deal with the global job market. Highway funds go to rural areas, not to cities that need them more; job creation money goes to wealthy areas, not to the core of battered cities.

Some urban regions have more or less given up any hope that their state will ever change or be a positive partner, such as Kansas City, as Longworth notes:

When the Greater Kansas City Community Foundation issued a report on the city’s future, it pretty much told the state to get out of the way. “Nations and states still matter,” it said. “They particularly can do their cities harm. But cities have to take the lead. San Diego did not become San Diego by looking to Sacramento, not Seattle to Olympia.” When the authors talked about Sacramento and Olympia, one felt their really meant Jefferson City.

I’d probably go even further than Longworth. I think that historically states imposed rules on cities deliberately designed to hobble their growth. For example, the laws that restricted branch banking in most states until recently had the effect of keeping big city banks from buying up rural and small town banks around the state. The end game of course is that when deregulation occurred, the banks in most big cities were so small because of these rules, they were easy prey to out of state acquirers. Thus most states saw basically their entire indigenous banking industry swallowed up.

Also, states seem to more or less treat their urban regions like ATM machines. Every study I’ve seen documents how, contrary to popular belief, cities actually are net exporters of tax dollars to their state government. Marion County, Indiana for example (Indianapolis), sends a net of about $400 million a year to the state – enough to cover the entire public safety budget of the city.

I actually don’t have a problem with some redistribution as cities are generally economic engines and more efficient to boot, so they should be expected to be donors at some level. On the other hand, when states proceed to starve those cities of the critical funds they need stay healthy and strip them of the powers they need to manage their own affairs, this is like sticking a knife in the golden goose.

Again I can use Indianapolis as an example. As part of a tax reform package the state took over all operating educational funding for K-12. So far so good. But they also imposed a funding formula that severely disadvantaged growing suburban districts by denying them equal per pupil funding. The net result was a major funding problem for the best suburban Indianapolis districts like Carmel, Fishers, etc. Many of these districts had to go to referendums to raise local taxes to make up the difference (which was no doubt the state’s plan all along – it simply outsourced the unpleasantries of a tax increase to localities). Here is a state that claims it wants to be in the biotech business, the high tech business, etc, yet it singles out the school districts where the labor force you are trying to attract for those industries is likely to live for outsized cuts. That hardly seems like a winning strategy.

Indiana also keeps its cities on a tight leash, with some of the weakest home rule powers around. Indianapolis basically can’t do much without legislative approval (a transit referendum, for example, will require specific legislative authorization). And the legislature seems to like it that way. Indiana’s property tax caps, which I support generally from a percentage of assessment perspective, include a lot of poorly advertised gotchas. For example, regardless of assessed value, the total tax levy can only grow at a rate equal to the average personal income growth over the last six years. I’ll caveat this by saying I haven’t studied this in detail and thus may be a bit off base, but the levy cap appears to be a de facto spending cap at current levels regardless in growth of tax base. This may be ok for some, but not others that are growing say their commercial office space base at a rapid clip and need to expand infrastructure and services to support it.

Clearly many of these policies have no real benefit to the Indianapolis region, which is more or less being asked to be the economic engine of the state and finance state government without being given the tools to do that job property.

The list goes on but that should give you a flavor. Similar things occur around the country.

To this list I’ll add one of my own, which has also been richly illustrated by Jim Russell. Namely,

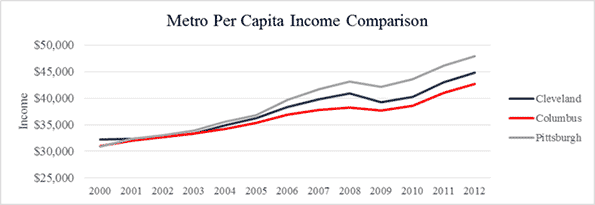

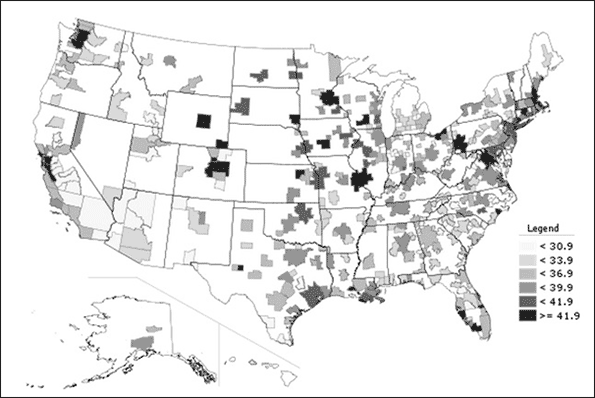

5. States can’t to much to help, but they can do a lot to hurt. A lot of the national debate seems to center on whether the “red state” or “blue state” model makes the most sense. But to a great extent, policy almost doesn’t matter. In Ohio, with one set of state policies, Columbus thrives while Cleveland struggles. Tennessee is a right to work state with no income tax, but Nashville booms while Memphis stagnates. Texas is doing great with its red state model, but Mississippi and Alabama not so much. And even within Texas, there are plenty of places that are hurting badly.

While good policy can set the stage for growth, it can’t guarantee local economies will prosper. But bad policies can hurt regions that otherwise would thrive. Extremes of either the blue or red model seem to lead to problems. Witness California, for example, which seems to be holding up a sign to business saying, “Get lost.”

This puts states in the difficult position of being almost being able to aspire at best to being a neutral influence on their own economy. But it’s easy for them to screw things up.

This piece first appeared at The Urbanopihle on July 11, 2011.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs and the founder of Telestrian, a data analysis and mapping tool. He writes at The Urbanophile, where this piece originally appeared.

States map image by Bigstock.

![]()

a collection of historical travel essays. His new book,

a collection of historical travel essays. His new book,