The San Francisco Bay Area (San Jose-San Francisco combined statistical area or CSA) has a superior access to work systems, including its important work at home element. The freeway system provides primary access between all points, importantly supplemented by arterial streets, and accounts for nearly 70 percent of all work trips. There are more types of transit than in other metropolitan regions (metro, street car, commuter rail, light rail, ferry, and cable car) and generally with a higher level of service. The Silicon Valley virtually defines information technology and is behind the huge increase in working at home, much of it telecommuting.

The recently released American Community Survey five-year file provides the opportunity to examine state of employment access in all Bay Area municipalities

Employment Access by Car

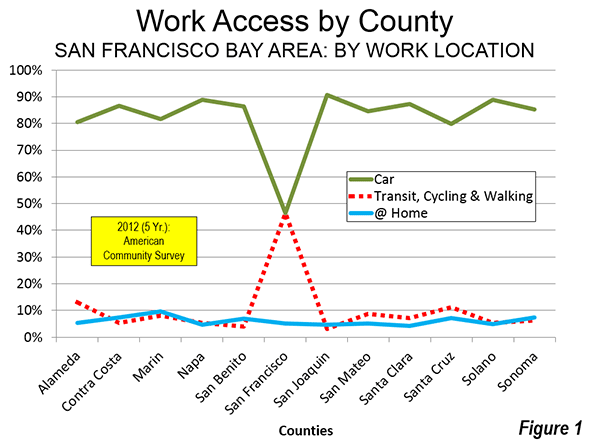

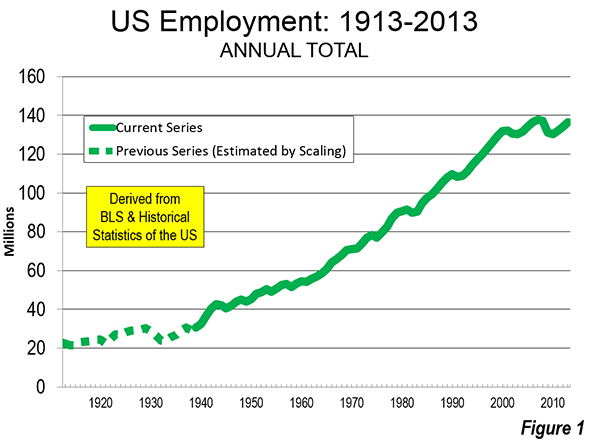

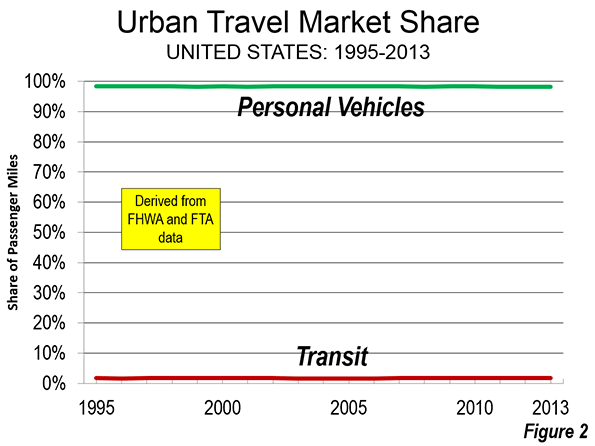

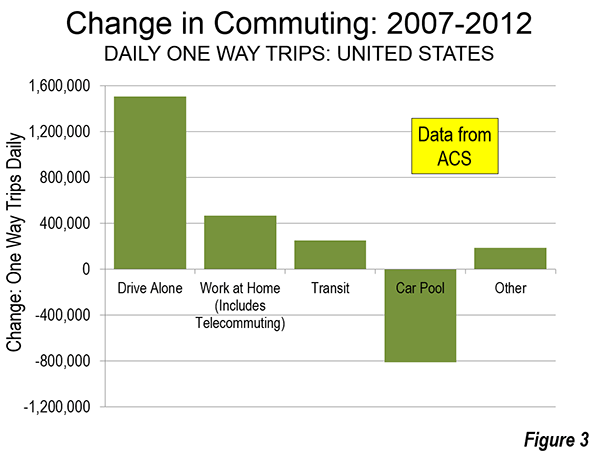

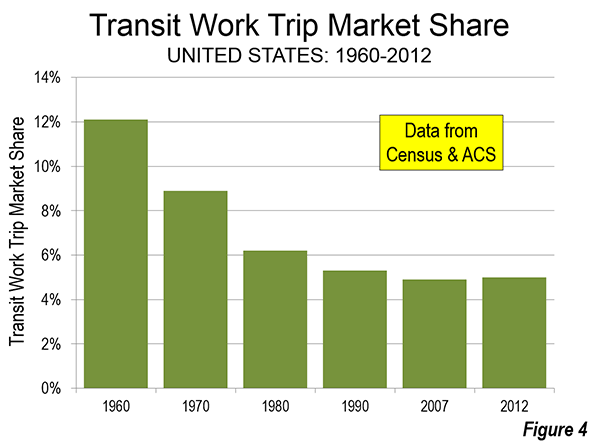

Like every major metropolitan area in the United States, more people use cars or light trucks (for simplicity called "cars" in this article) to get to work than any other mode of transport. In the Bay Area, 68 percent of commuting is by car. Cars provide the overwhelming majority of work access to jobs in 11 of the Bay Area's 12 counties. This ranges from 80 percent in Alameda County (secondary core municipality Oakland is the county seat) to 91 percent in San Joaquin County, which was recently added to the San Jose-San Francisco CSA (Figure 1). In the 12th county, San Francisco, cars provide work access for nearly equal to that of transit, walking and cycling combined (both approximately 46 percent).

Employment Access from Home

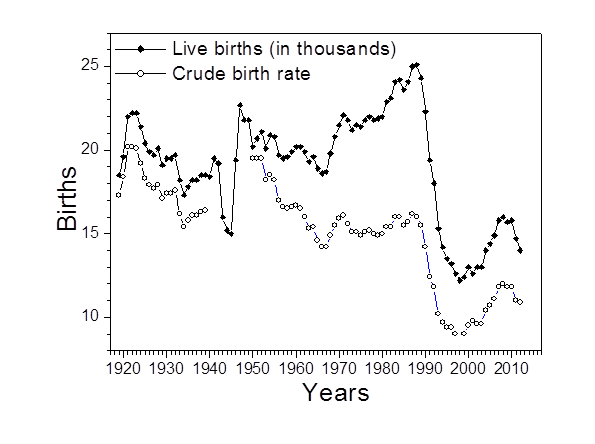

Working at home continues to grow and, to an even greater extent than car travel, is relatively evenly distributed throughout the 12 Bay Area counties. The highest percentage is in Marin County, at 9.6 percent. The combination of a technology friendly regional environment and horrific traffic on the primary commuting routes to most of the Bay Area (US-101 and the Golden Gate Bridge) probably drive this figure higher. Contra Costa County and Santa Cruz County also have a high work at home shares, at 7.3 percent and 7.1 percent respectively. This is than 50 percent above the national rate.

Most surprisingly, however, the lowest work at home share in the Bay Area is in Santa Clara County, the very heart of Silicon Valley. This is slightly less than the national average. Another surprise is counties on the periphery of the Bay Area also have small work at home shares. Sonoma, Napa and San Joaquin counties have work at home shares of under 5.0 percent.

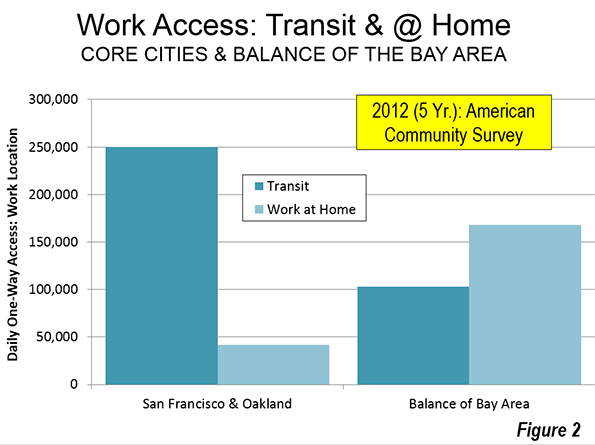

Outside the core cities of San Francisco and Oakland, more than 1.5 times as many employees work at home (including telecommuting) than access work by transit (Figure 2).

Employment Access by Transit

The Bay Area remains monocentric only in aerial photographs and transit market share. San Francisco is served by one of the nation's busiest metro (subway or underground) systems in the nation, Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART), which carries over 400,000 one-way rides daily. BART was the first of the major post-World War II rapid transit systems in the United States and was followed by other fully grade separated Metro systems in Washington and Atlanta and individual lines in Los Angeles.

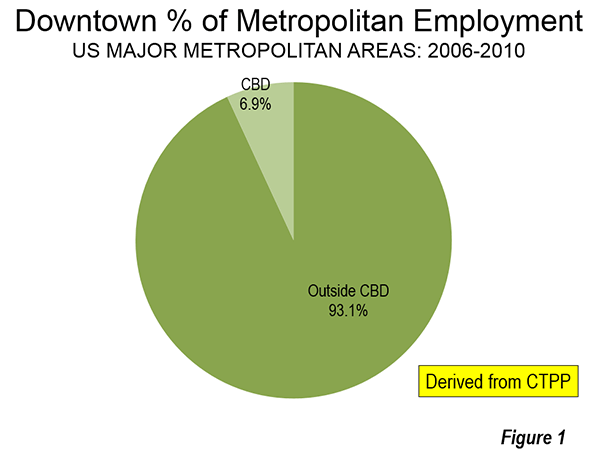

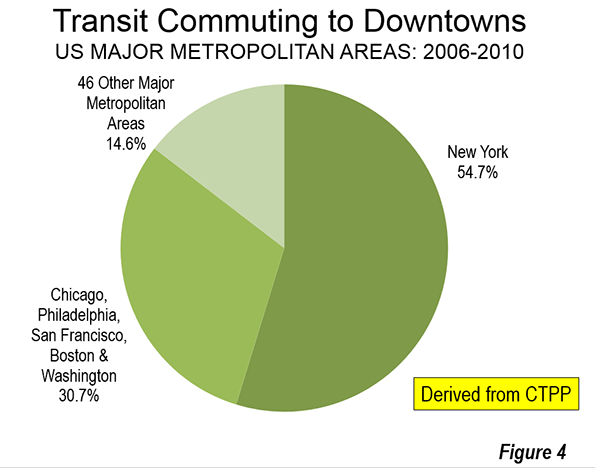

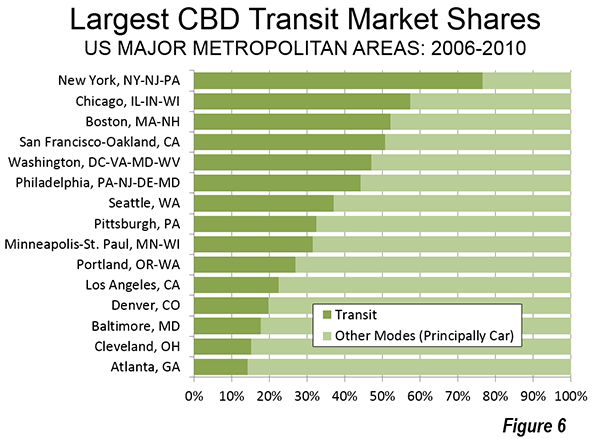

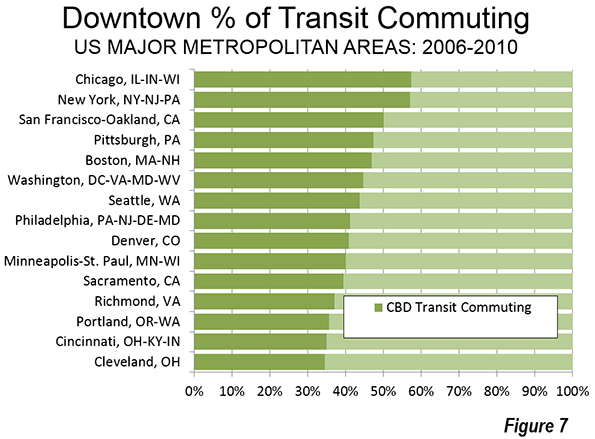

As we indicated in Transit Legacy Cities, most of the transit commuting (55 percent) in the United States is to just six core municipalities, New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, Washington, and San Francisco. Approximately 60 percent of commuting to those cities is to the downtown areas, which are also the largest in the United States. Yet these legacy cities, with a majority of the nation's transit commuting, account for only six percent of the nation's employment.

Nearly two-thirds of Bay Area transit commuters work in the city of San Francisco and that figure rises to more than 70 percent, including the city of Oakland, with its strong downtown. Yet, these two core cities have only 21 percent of employment in the Bay Area. The downtowns of both core cities are well served by transit, including BART and radial surface transit systems. Buses serve downtown Oakland, while buses, trolley buses (electric buses), street cars and cable cars are focused on downtown San Francisco.

The Non-Centered Metropolis

Even with a regional Metro system, the Bay Area has developed in a strongly dispersed and polycentric form. Polycentricity is represented by edge cities (suburban office centers) such as Walnut Creek (with a BART station), the San Francisco Airport office area (not generally walkable from any rapid transit) and in the Silicon Valley (San Mateo and Santa Clara counties). Even more, however, employment is dispersed well beyond even these nodes. Authors Robert Lang and Jennifer LeFurg have called this phenomenon "edgeless cities," though their other term, the "non-centered metropolis," says it better.

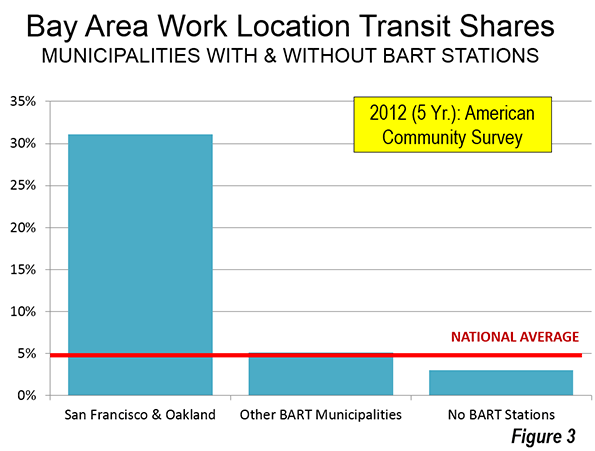

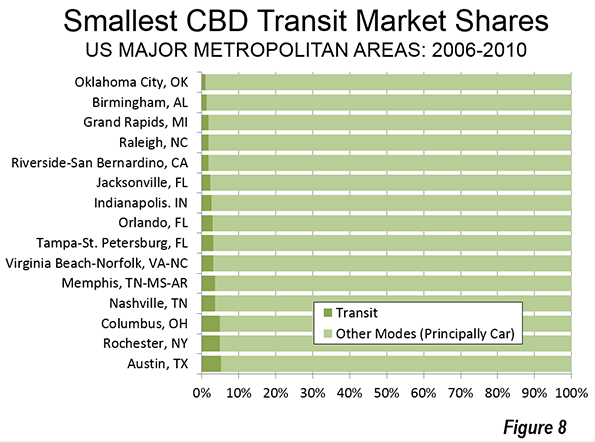

Outside the San Francisco-Oakland core, the commuting pattern in the Bay Area is little different than in the rest of the nation (as is also the case in New York, outside the urban core). Nearly 80 percent of the Bay Area's jobs are outside the cities of San Francisco and Oakland, however only 4.0 percent of commuters use transit to jobs located outside these cores. Among municipalities other than San Francisco and Oakland with BART stations, work access by transit is 5.1 percent, only slightly higher than the national average (which includes all urban and rural areas). Commuting by transit is even lower (3.0 percent) to jobs in outside municipalities with BART stations (Figure 3).

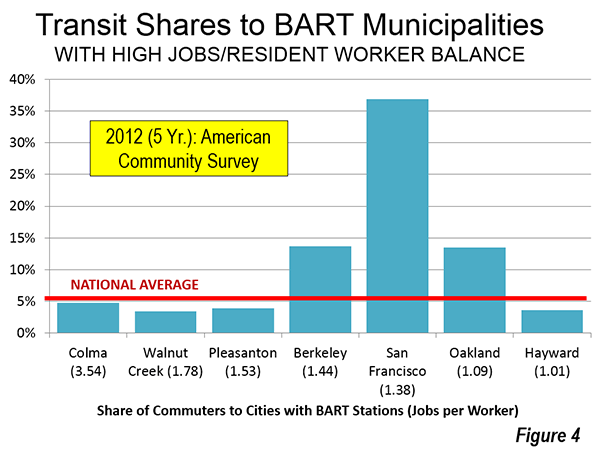

Among the municipalities with BART stations and favorable "jobs-housing balances," only San Francisco, Oakland and Berkeley (home of the University of California) attract more transit commuters than the national average. Walnut Creek illustrates the problem of regional transit commuting to suburban locations. Walnut Creek has a strong suburban office center and a stronger jobs-housing balance than all BART municipalities but much smaller Colma. Yet, only 3.5 percent of commuters who work in Walnut Creek used transit to get to work (Figure 4).

Overall, outside the core cities of San Francisco and Oakland, approximately 20 times as many people commute to jobs by car as by transit.

The Illusion of Monocentricity

With transit's failure to carry large numbers of workers to jobs throughout the Bay Area (not just to the two older core municipalities), planners have switched strategies. Now the focus is on urban villages (transit oriented development), by which people and jobs will be located close together, reducing the need for long automobile commutes. The adopted regional plan, "Plan Bay Area" imagines people living in transit oriented developments and walking, cycling or using transit to get to employment. However, former principal planner of the World Bank Alain Bertaud says that this "urban village model exists only in the mind of urban planners" and worse, that "it contradicts the economic justification of large cities: the efficiency of large labor markets." (see: Urban Planning 101) That means a lower standard of living and more poverty.

The reality for the Bay Area and for metropolitan areas around the world is that transit is structurally incapable of replacing the automobile for the bulk of the workforce. The fundamental problem is that no transit system can attract drivers to jobs by offering travel times competitive with the automobile (Note). Transit can compete to some downtowns, but downtowns have only a small minority of employment. Outside of those, trip patterns are simply too dispersed for transit to serve as well as cars. Monocentric cities, to duplicate Bertaud's logic, exist "only in the mind of urban planners."

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.

--------------

Note: In 2003, I issued a challenge to identify an existing or proposed transit system design that would achieve automobile competitiveness throughout a metropolitan area of more than 1,000,000 in Western Europe or the United States (see: Smart Growth Challenge: Transportation Choice for All, Not Just a Few[Automobile Competitiveness]). No complete responses were received. This is not surprising. In 2007, Professor Jean-Claude Ziv and I authored a paper for the 11th World Conference on Transport Research (2007 WCTRS) that estimated such a system could cost as much as the total gross domestic product of any such metropolitan area each year).

Photo: Bart A car Oakland Coliseum Station

a collection of historical travel essays. His new book,

a collection of historical travel essays. His new book,