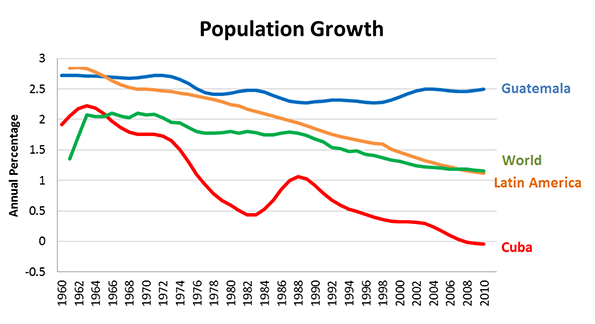

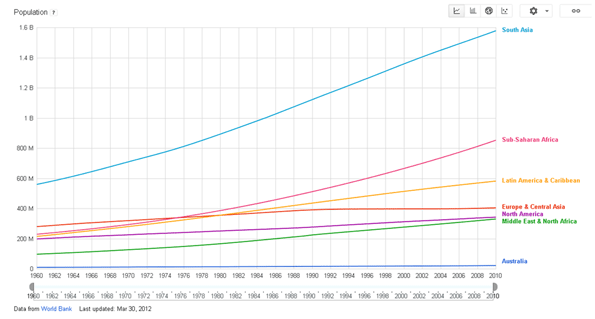

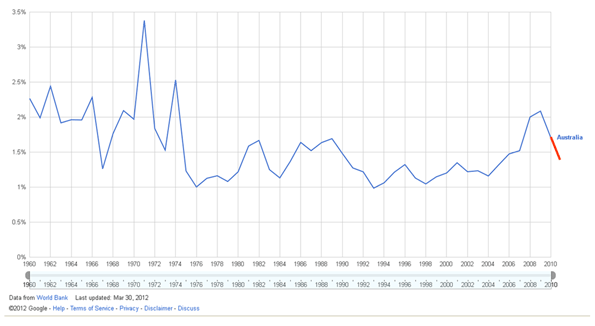

Many global population projections point to the current world population of roughly seven billion people peaking at around nine to ten billion in 2050, after which numbers will slowly decline. In the midst of this growth, Australia’s current population of 23 million is predicted to rise to around 30 or 35 million in the same period. This low growth outlook has been called ‘big Australia.’ We are kidding ourselves, aren’t we?

‘Populate or perish’ was a rallying cry of post-World War II Labor Immigration Minister Arthur Calwell as he sought to overcome domestic resistance to immigration. For Calwell, immigration was the key to quickly boosting Australia’s population numbers in the interests of economic and military security. An avowed supporter of the ‘white Australia policy’ he sought immigrants from European backgrounds. Asia was, back then, regarded as the enemy.

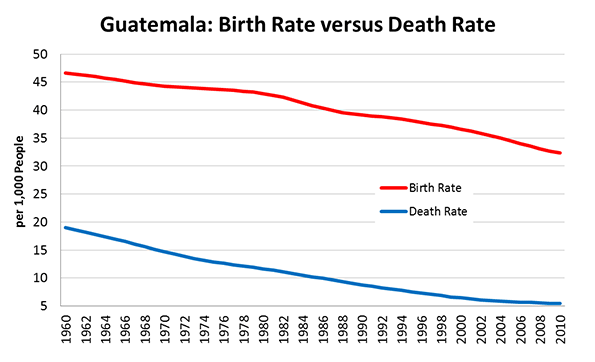

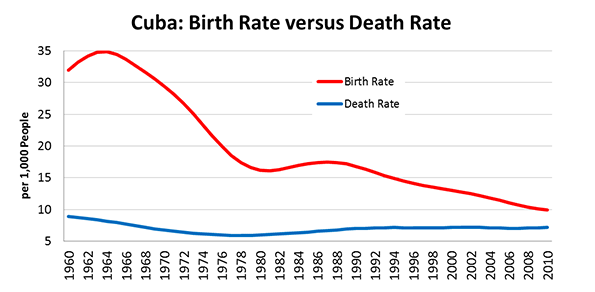

Above: world populations since 1960. Below: Australia’s rate of population growth since 1960. Source: World Bank.

How things change, yet stay the same. In 2012, it’s arguably just as much in Australia’s interests to boost its population numbers, in the interests of economic security and (according to some) military security also. And again, immigration – not an accelerated breeding program of naturalised Australians – is the only way this can realistically occur. As domestic industries increasingly surrender to global competition and as energy, agriculture and services industries increasingly depend on foreign markets for their long term survival, the issue of Australia’s relatively small population – despite its huge continental mass – raises little by way of public debate. A larger domestic population might provide markets for domestic industries, for local employment and for community wide infrastructure.

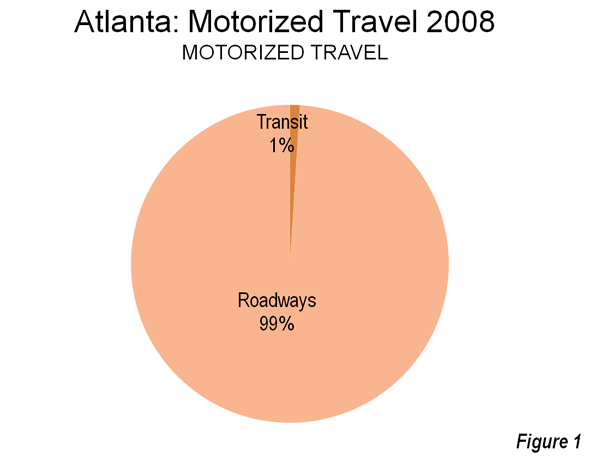

In contrast the planning fraternity’s dreams of Parisian, London, or New York standards of public transport, for example, will never succeed. Our cities are simply too small to make this work.

But talk of a ‘big Australia’ has become ‘persona non grata’ in public policy circles. We have a Federal Population Minister, but he hasn’t issued a single statement on population policy this year. Our Prime Minister has other things on her mind, but even if her government was on more solid ground her antipathy to a ‘big Australia’ is well known and a matter of public record. And such is the apparent public hostility to the notion of a bigger population, intermixed as it is with a blend of doomsday environmentalism and references to failed Malthusian or Paul Ehlrich ‘Population Bomb’ scenarios and myths (suggesting that Australia is running out of room and resources), that few political or public policy leaders want to take up the debate in favour of growth.

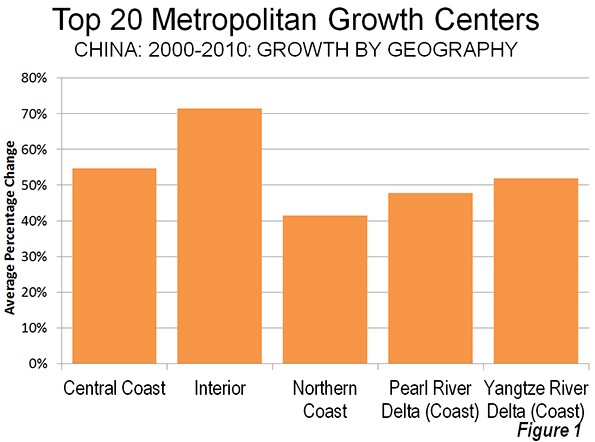

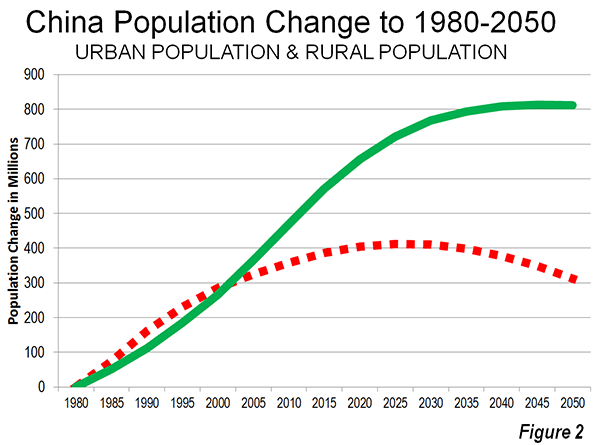

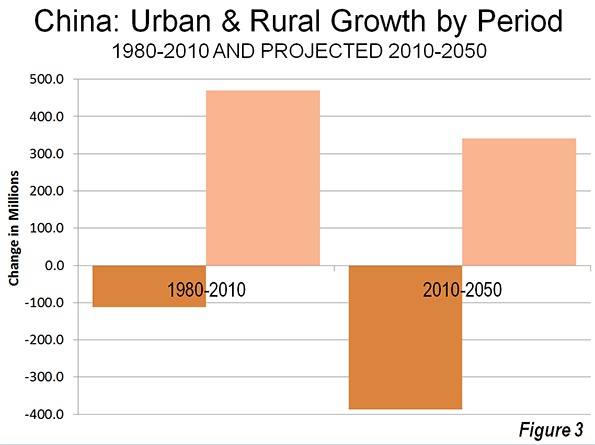

With that in mind, I thought some very simple reality checks might prove helpful to stimulate your thinking about Australia’s population capacity relative to the rest of the world. Wendell Cox, author of the global housing affordability study ‘Demographia’ recently published his Demographia World Urban Areasreport with this summary on New Geography. I want to take just two examples and interpose them into the Australian context.

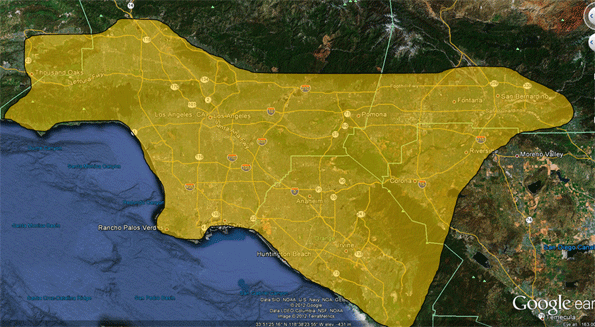

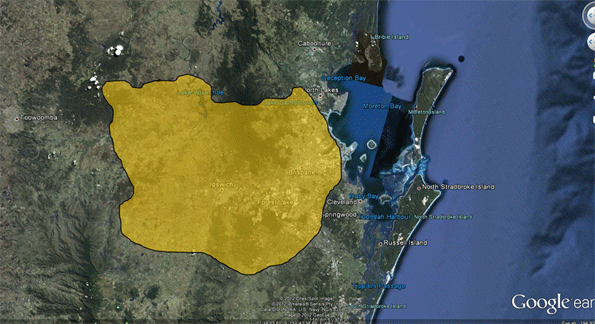

First, let’s look at Los Angeles, California. Often cited as a region with similarities to the Australian urban context (both in a positive and negative sense), this city popularly known for its ‘sprawl’ actually has a very high level of population density. The total population of the Greater Los Angeles area is around 15 million people. Put into context, that’s roughly two thirds of the entire population of Australia living in the Greater Los Angeles ‘sprawl.’

Above: The greater Los Angeles area and below, the same area superimposed in south east Queensland.

Put into a visual context, the contrast is even more apparent. At LA levels of population density, roughly the area we know of as south east Queensland could accommodate some 15 million people comfortably. Yet the conventional “wisdom” is that with just 3 million people it’s bursting at the seams and can’t possibly take any more

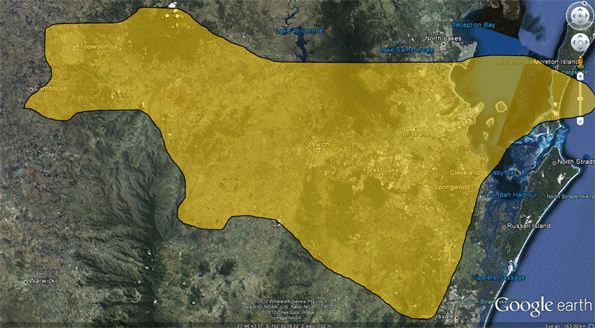

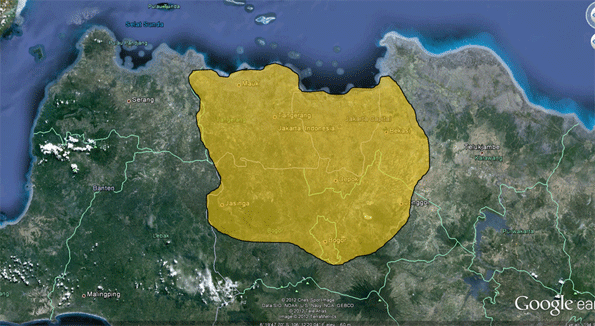

A more extreme example, just to stretch the imagination further, is worth thinking about. Jakarta, Indonesia (our nearest large foreign neighbour) has a population of 26 million people. That’s more than the entire population of Australia, living in one (very crowded) city – at the rate of 9,400 people per square kilometre.

Now, I’m not wishing that sort of urban density (and in large part, misery) on anyone in Australia, but the hypothetical comparison still applies, for the sake of discussion only. The footprint of greater urban Jakarta, home to 26 million people, easily fits within the boundary of south east Queensland. In fact, it doesn’t even require the Gold or Sunshine Coasts to do it. Imagine this: the entire population of Australia, crammed as it would be into this super-compact urban footprint, and not a single soul living anywhere else on the entire continent?

Above: Jakarta’s footprint and below, the same footprint – home to 26 million people – superimposed on south east Queensland.

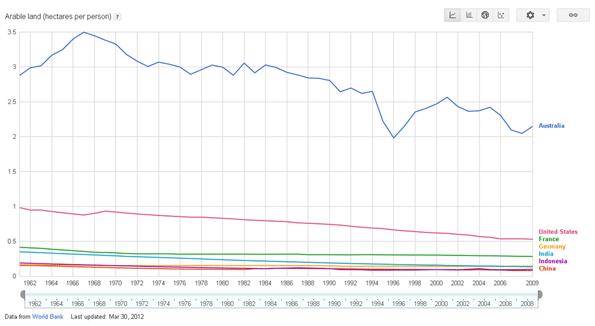

The argument that Australia is somehow incapable of supporting substantially larger population relies on a myth that we short of room. Nor can it rely on suggestions that we would exhaust our energy stocks (we are a net exporter and would remain so at much larger population numbers), nor our food production capacity (again, we are a net exporter and would remain so even with much higher levels of population). In fact, in terms of food production, a lack of domestic market scale poses a significant problem for producers. The efficiency gains of primary production (livestock to cropping) have outpaced the growth in population.

There is an argument regularly raised that Australia has insufficient water supply to support much larger population numbers but this argument doesn’t hold water (sorry, couldn’t help that) either. What we do lack is water storage by way of dams, but the environmental lobby has vigorously opposed almost every proposed dam in the last 30 years whether for domestic supply, agriculture or hydro energy. The lack of water storage has been a policy decision made by successive governments for varying political reasons.

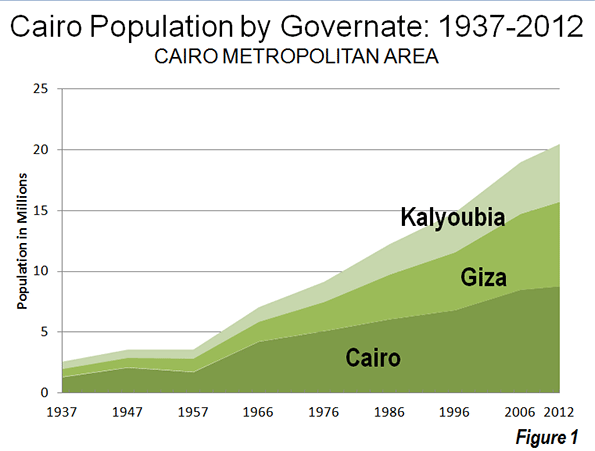

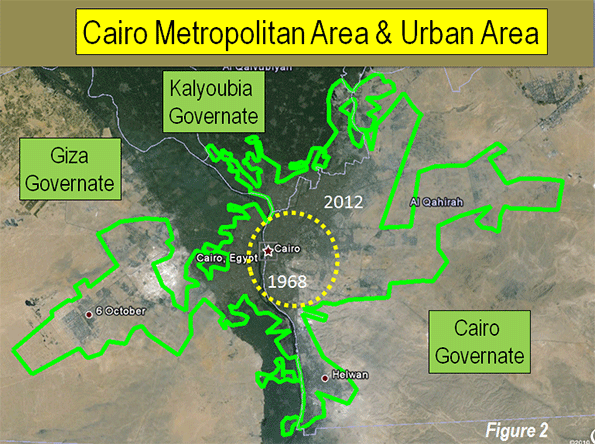

Think also for a moment how cities like Mexico City (population nearly 20 million people) or Cairo (population 18 million) or even countries like Morocco (population 32 million in 500,000 square kilometres on the edge of the Sahara compared with Australia’s 7.6 million square kilometres) manage for water? For Australia to claim it cannot support more people due to water limitations is a bit of joke.

Above: arable land area in hectares per person. Australia is well ahead of the field.

Infrastructure deficits are the other vexed issue raised by by those concerned with population growth. They have pointed out that infrastructure investment has not kept pace with population, and they’re right. The problem though is largely that strategic infrastructure investment in this country is something really only talked about. Instead, what typically happens is that billions are doled out on pet projects in marginal seats or designed to win over particular interest groups that some focus group or other suggests could hold the key to winning the next election. Politically motivated rail projects (especially in NSW), home insulation schemes, TV set box boxes, green energy schemes... the list of our nation’s capacity to waste vast sums quickly is pretty impressive. Our deficient national road network, our inadequate domestic water storage (in many areas), our looming potential energy problems (not just in price thanks to a carbon tax but also in terms of power generation shortages according to some experts) – the bigger and more strategic infrastructure priorities which would support growth seem to get the least attention. Witness the latest Federal Government budget. (Read what Infrastructure Partnerships Australia, among others critical of the budget, had to say here).

So the capacity to fund and deliver strategic infrastructure isn’t the issue. Inept public policy is.

Instead, do we have some other more deep seated aversion to a bigger population? And is this race based? Despite being a successful nation of immigrants ( are we fearful for our culture if we had more immigration? Environmental impacts are often publicly cited as the reason to oppose more people, but if the examples of Los Angeles or Jakarta are remembered, we could in theory house a great deal more people without encroaching on vast areas of natural terrain.

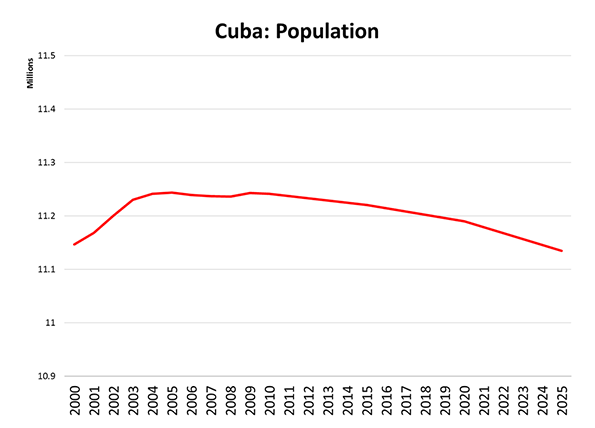

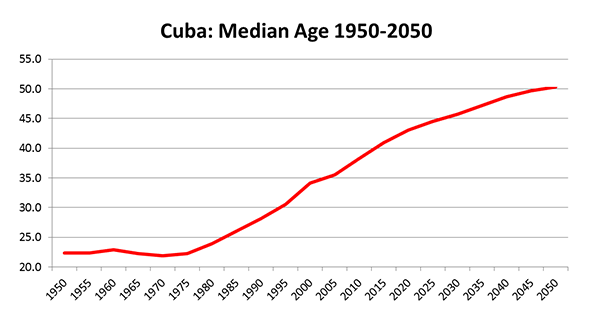

Another big reason to reconsider objections to a ‘big Australia’ is the ticking clock on Australia’s ageing population. Even the Federal Government’s own ‘Tax Reform Roadmap’ released with the May budget warned that: “The proportion of working age people is projected to fall markedly over the coming decades. Today there are about 4.8 people of traditional working age for every person aged 65 and over. This is expected to fall to around 4 people within the next 10 years and to around 2.7 people by 2050.”

Australia’s current rate of population growth is hovering around 1.4%. We are just shy of 23 million people. We say we’re concerned about getting to 35 million by 2050, by which time the world population will have increased by 2 billion people. We know that our ageing population will struggle to be supported by a diminished workforce and that we lack sufficient critical mass to sustain a variety of industries in the face of global competition. Yet we consistently refuse to confront the question of a larger population and the consequences of failing to have one.

Ultimately even if we agree collectively to prefer to remain a small nation of less than 30 million, it’s a discussion we need to be having. Pretending the issue isn’t there won’t do anyone any good.

Ross Elliott has more than 20 years experience in property and public policy. His past roles have included stints in urban economics, national and state roles with the Property Council, and in destination marketing. He has written extensively on a range of public policy issues centering around urban issues, and continues to maintain his recreational interest in public policy through ongoing contributions such as this or via his monthly blog The Pulse.

Australia graphic by Bigstockphoto.com.