Few states have offered the class warriors of Occupy Wall Street more enthusiastic support than California has. Before they overstayed their welcome and police began dispersing their camps, the Occupiers won official endorsements from city councils and mayors in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland, Richmond, Irvine, Santa Rosa, and Santa Ana. Such is the extent to which modern-day “progressives” control the state’s politics.

But if those progressives really wanted to find the culprits responsible for the state’s widening class divide, they should have looked in a mirror. Over the past decade, as California consolidated itself as a bastion of modern progressivism, the state’s class chasm has widened considerably. To close the gap, California needs to embrace pro-growth policies, especially in the critical energy and industrial sectors—but it’s exactly those policies that the progressives most strongly oppose.

Even before the economic downturn, California was moving toward greater class inequality, but the Great Recession exacerbated the trend. From 2007 to 2010, according to a recent study by the liberal-leaning Public Policy Institute of California, income among families in the 10th percentile of earners plunged 21 percent. Nationwide, the figure was 14 percent. In the much wealthier 90th percentile of California earners, income fell far less sharply: 5 percent, only slightly more than the national 4 percent drop. Further, by 2010, the families in the 90th percentile had incomes 12 times higher than the incomes of families in the 10th—the highest ratio ever recorded in the state, and significantly higher than the national ratio.

It’s also worth noting that in 2010, the California 10th-percentile families were earning less than their counterparts in the rest of the United States—$15,000 versus $16,300—even though California’s cost of living was substantially higher. A more familiar statistic signaling California’s problems is its unemployment rate, which is now the nation’s second-highest, right after Nevada’s. Of the eight American metropolitan areas where the joblessness rate exceeds 15 percent, seven are in California, and most of them have substantial minority and working-class populations.

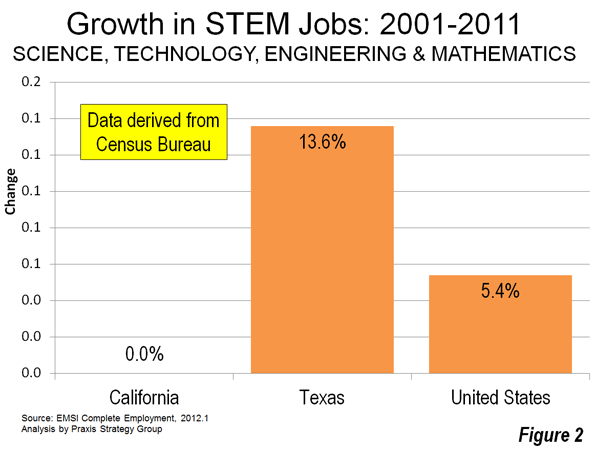

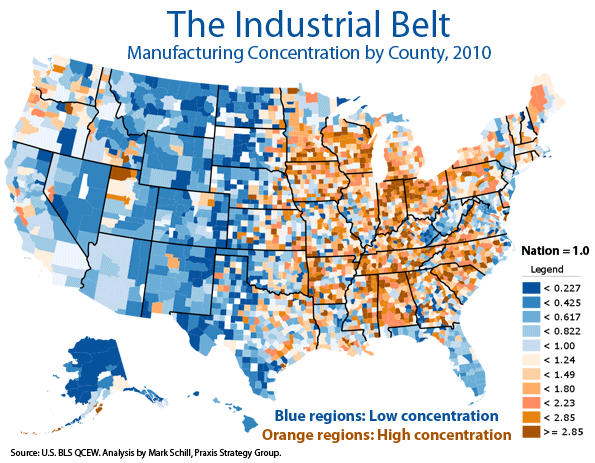

When California’s housing bubble popped, real-estate prices fell far more steeply than in less regulated markets, such as Texas. The drop hurt the working class in two ways: it took away a major part of their assets; and it destroyed the construction jobs important to many working-class, particularly Latino, families. The reliably left-leaning Center for the Continuing Study of the California Economy found that between 2005 and 2009, the state lost fully one-third of its construction jobs, compared with a 24 percent drop nationwide. California has also suffered disproportionate losses in its most productive blue-collar industries. Over the past ten years, more than 125,000 industrial jobs have evaporated, even as industrial growth has helped spark a recovery in many other states. The San Francisco metropolitan area lost 40 percent of its industrial positions during this period, the worst record of any large metro area in the country. In 2011, while the country was gaining 227,000 industrial jobs, California’s manufacturers were still stuck in reverse, losing 4,000.

Yet while the working and middle classes struggle, California’s most elite entrepreneurs and venture capitalists are thriving as never before. “We live in a bubble, and I don’t mean a tech bubble or a valuation bubble. I mean a bubble as in our own little world,” Google CEO Eric Schmidt recently told the San Francisco Chronicle. “And what a world it is. Companies can’t hire people fast enough. Young people can work hard and make a fortune. Homes hold their value.” Meanwhile, in nearby Oakland, the metropolitan region ranks dead last in job growth among the nation’s largest metro areas, according to a recent Forbes survey, and one in three children lives in poverty.

One reason for California’s widening class divide is that, for a decade or longer, the state’s progressives have fostered a tax environment that slows job creation, particularly for the middle and working classes. In 1994, California placed 35th in the Tax Foundation’s ranking of states with the lightest tax burdens on business; today, it has plummeted to 48th. Only New York and New Jersey have more onerous business-tax burdens. Local taxes and fees have made five California cities—San Francisco, Los Angeles, Beverly Hills, Santa Monica, and Culver City—among the nation’s 20 most expensive business environments, according to the Kosmont–Rose Institute Cost of Doing Business Survey.

Still more troubling to California employers is the state’s regulatory environment. California labor laws, a recent U.S. Chamber of Commerce study revealed, are among the most complex in the nation. The state has strict rules against noncompetition agreements, as well as an overtime regime that reduces flexibility: unlike other states, where overtime kicks in after 40 hours in a given week, California requires businesses to pay overtime to employees who have clocked more than eight hours a day. Rules for record-keeping and rest breaks are likewise more stringent than in other states. The labor code contains tough provisions on everything from discrimination to employee screening, the Chamber of Commerce study notes, and has created “a cottage industry of class actions” in the state. California’s legal climate is the fifth-worst in the nation, according to the Institute for Legal Reform; firms face far higher risks of nuisance and other lawsuits from employees than in most other places. In addition to these measures, California has imposed some of the most draconian environmental laws in the country, as we will see in a moment.

The impact of these regulations is not lost on business executives, including those considering new investments or expansions in California. A survey of 500 top CEOs by Chief Executive found that California had the worst business climate in the country, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce calls California “a difficult environment for job creation.” Small wonder, then, that since 2001, California has accounted for just 1.9 percent of the country’s new investment in industrial facilities; in better times, between 1977 and 2000, it had grabbed 5.6 percent.

Officials, including Governor Jerry Brown, argue that California’s economy is so huge that it can afford to lose companies to other states. But for the local economy to be hurt, firms don’t have to leave entirely. Business consultant Joe Vranich, who maintains a website that tracks businesses that leave the state, points out that when California companies decide to expand, often they do so in other parts of the U.S. and abroad, not in their home environment. Further, Brown is too cavalier about the effects of businesses’ departure. As Vranich notes, many businesses leave California “quietly in the night,” generating few headlines but real job losses. He cites the low-key departure in 2010 of Thomas Brothers Maps, a century-old California firm, which transferred dozens of employees from its Irvine headquarters to Skokie, Illinois, and outsourced the rest of its jobs to Bangalore.

The list of companies leaving the state or shifting jobs elsewhere is extensive. It includes low-tech companies, such as Dunn Edwards Paints and fast-food operator CKE Restaurants, and high-tech ones, such as Acacia Research, Biocentric Energy Holdings, and eBay, which plans to create 1,000 new positions in Austin, Texas. Computer-security giant McAfee estimates that it saves 30 to 40 percent every time it hires outside California. Only 14 percent of the firm’s 6,500 employees remain in Silicon Valley, says CEO David DeWalt. The state’s small businesses, which account for the majority of employment, are harder to track, but a recent survey found that one in five didn’t expect to remain in business in California within the next three years.

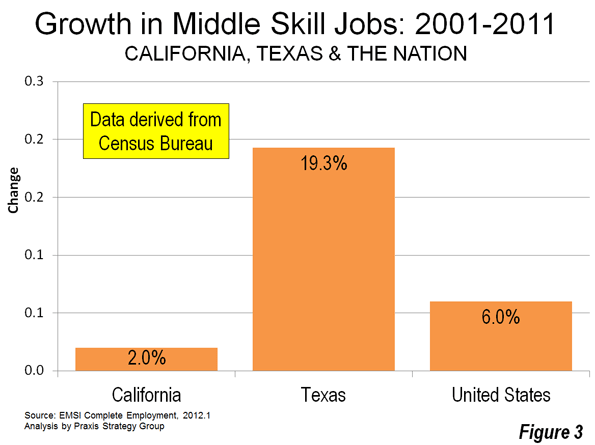

Apologists for the current regime also claim that the state’s venture capitalists will fund and create new companies that will boost employment. It’s certainly true that in the past, California firms funded by venture capital tended to expand largely in California. But as Jack Stewart, president of the California Manufacturing and Technology Association, points out, a different dynamic is at work today: once a company’s start-up phase is over, it tends to move its middle-class jobs elsewhere, as the state’s shrinking fraction of the nation’s industrial investment indicates. “Sure, we are getting half of all the venture capital investment, but in the end, we have relatively small research and development firms only,” Stewart argues. “Once they have a product or go to scale, the firms move [employment] elsewhere. The other states end up getting most of the middle-class jobs.”

Radical environmentalism has been particularly responsible for driving wedges between California’s classes. Until fairly recently, as historian Kevin Starr says, California’s brand of progressivism involved spurring economic growth—particularly by building infrastructure—and encouraging broad social advancement. “What the progressives created,” Starr says, “was California as a middle-class utopia. The idea was if you wanted to be a nuclear physicist, a carpenter, or a cosmetologist, we would create the conditions to get you there.” By contrast, he says, today’s progressives regard with suspicion any growth that requires the use of land and natural resources. Where old-fashioned progressives embraced both conservation and the expansion of public parks, the new green movement advocates a reduced human “footprint” and opposes cars, “sprawl,” and even human reproduction.

The Bay Area has served as the incubator for the new green progressivism. The militant Friends of the Earth was founded in 1969 in San Francisco. Malthusian Paul Ehrlich, author of the sensationalist 1968 jeremiad The Population Bomb and mentor of President Obama’s current science advisor, John Holdren, built his career at Stanford. Today, more than 130 environmental activist groups make their headquarters in San Francisco, Berkeley, Oakland, and surrounding cities.

The environmentalist agenda emerged in full flower under nominally Republican governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, who initially cast himself as a Milton Friedman–loving neo-Reaganite. On his watch, California’s legislature in 2006 passed Assembly Bill 32, which, in order to cut greenhouse-gas emissions, imposes heavy fees on using carbon-based energy and severely restricts planning and development. One analysis of small-business impacts prepared by Sacramento State University economists indicates that AB 32 could strip about $181 billion per year, or nearly 10 percent, from the state’s economy. At the same time, land-use regulations connected to the climate-change legislation hinder expansion for firms.

Another business-hobbling mandate is the law requiring that 30 percent of California’s electricity be generated by “renewable” sources by 2020. The state’s electricity costs are already 50 percent above the national average and the fifth-highest in the nation—yet state policies make the construction of new oil- or gas-fired power plants all but impossible and offer massive subsidies for expensive, often unreliable, “renewable” energy. The renewable-fuel laws will simply boost electricity costs further. The cost of electricity from the new NRG solar-energy facility in central California, for instance, will be 50 percent higher than the cost of power from a newly built gas-powered facility, according to state officials. For providing this expensive service, NRG will pay no property taxes on its facilities. By some estimates, green mandates could force electricity prices to rise 5 to 7 percent annually through 2020.

The renewable-fuel regulations are driving even green jobs out of the state. Cereplast, a thriving El Segundo–based manufacturer of compostable plastic, last year moved its manufacturing operations to Indiana, where electricity costs are 70 percent lower. Fuel-cell firm Bing Energy cited cost and regulatory factors when announcing its move from California to Florida. “I just can’t imagine any corporation in their right mind would decide to set up in California right now,” the firm’s CFO, Dean Minardi, told the Inland Valley Daily Bulletin. Still more rules, aimed at improving water quality and protecting endangered species, could have a devastating effect on the construction and expansion of port facilities, which tend to sustain high-wage blue- and white-collar jobs.

The political class largely ignores the economic consequences of these policies. Indeed, Governor Brown and others insist that they will create jobs—upward of 500,000 of them—while establishing California as a green-energy leader. To turn Brown’s green dreams into reality, the state has approved enormous subsidies and tax breaks for solar and other renewable-energy producers to supplement those dispensed by the Obama administration. Yet for all this, California has barely 300,000 “green jobs,” many of which are low-wage positions, such as weather-stripping installers. And the solar industry, in California and abroad, is imploding.

Bill Watkins, head of the economic forecasting unit at California Lutheran University, notes that California’s green policies affect the very industries—manufacturing, home construction, warehousing, and agribusiness—that have traditionally employed middle- and working-class residents. “The middle-class economy is suffering since there is no real opposition to the environmental community,” says Watkins. “You see the Democrats, who should worry about blue-collar and middle-income jobs, give in every time.”

Progressives and many Occupy protesters mourned the death of high-tech innovator and multibillionaire Steve Jobs. They also tend to view social-networking firms like Facebook more as allies than as class enemies. This embrace of Silicon Valley is nearly as strange as the Occupy movement’s decision to target the ports of Los Angeles and Oakland—large employers of well-paid blue-collar workers. Activists portrayed the attempted port shutdowns as attempts to “disrupt the profits of the 1 percent,” but union workers largely saw them as impositions on their livelihood. As former San Francisco mayor and state assembly speaker Willie Brown wrote in the San Francisco Chronicle: “If the Occupy people really want to make a point about the 1 percent, then lay off Oakland and go for the real money down in Silicon Valley. The folks who work on the docks in Oakland or drive the trucks in and out of the port are all part of the 99 percent.”

The explanation for the progressives’ hypocritical friendliness to Silicon Valley is simple: money and politics. Venture capitalists and highly profitable, oligopolistic firms like Google (with its fleet of eight private jets) invest heavily in green companies; they were also among the primary bankrollers of the successful opposition to a 2010 ballot initiative aimed at reversing AB 32. The digital elite has become more and more involved in local politics, with executives from Facebook, Twitter, and gaming website Zynga contributing heavily to the recent campaign of San Francisco mayor Ed Lee, for example. Lee has, in turn, been extremely kind to the digerati, extending a payroll-tax break to Twitter and a stock-option break to Zynga and other firms that may soon go public.

Hollywood manages to outdo even Silicon Valley in its class hypocrisy. Former actor Schwarzenegger doesn’t let his green zealotry stop him from owning oversize houses and driving fuel-gorging cars. Canadian-born director James Cameron, who contents himself with a six-bedroom, $3.5 million, 8,300-square-foot Malibu mansion, talks about the need to “stop industrial growth” and applauds the idea of a permanent recession. “It’s so heretical to everybody trying to recover from a recession economy—‘we have to stimulate growth!’ ” says Cameron. “Well, yeah. Except that’s what’s gonna kill this planet.”

According to the Tax Foundation, California residents already pay the nation’s sixth-highest state tax rates, and they are likely to keep rising. Three tax-raising measures have already been proposed for the November 2012 ballot. Governor Brown’s proposal, which would boost both income and sales taxes, stands a good chance of passage. Hedge-fund manager Tom Steyer, an investor in environmental firms, has floated a measure that would raise taxes on out-of-state companies that conduct any operations in California and use some of the revenue to subsidize green-friendly building projects. And Molly Munger, a civil rights attorney and daughter of Warren Buffett’s longtime business partner, is pressing a measure to raise income taxes to fund schools. The so-called Think Long proposal, financed by nomadic French billionaire Nicolas Berggruen and overseen by a committee including Google’s Schmidt and billionaire philanthropist Eli Broad, proposes a mild cut in income-tax rates for the highest earners (like themselves) but new taxes on services provided by architects, accountants, business consultants, plumbers, gardeners, and others—the sole proprietors and microbusinesses that represent the one growing element in the state’s beleaguered private-sector middle class.

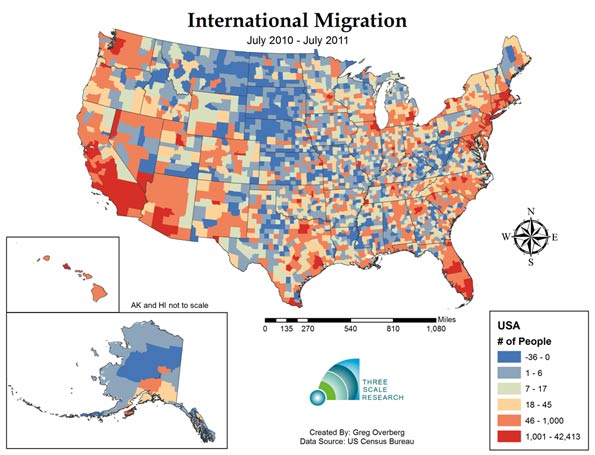

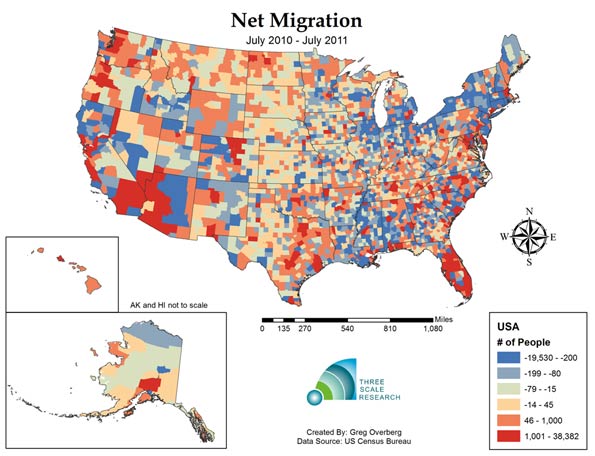

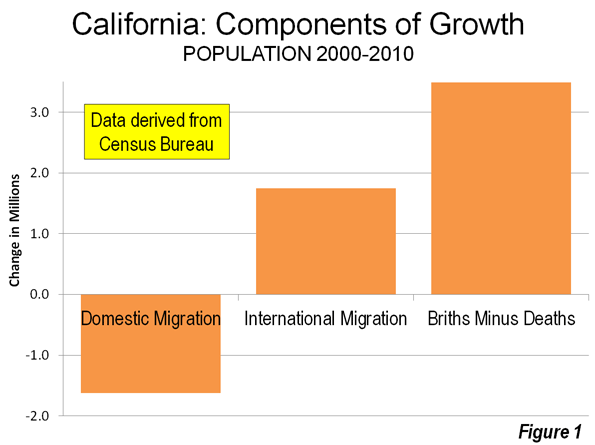

More money for social services or education might help alleviate some of the recession’s impact, but it cannot break the vicious cycle from which California currently suffers: weak growth leading to low tax revenues, government boosting taxes to make up the shortfall, and those higher taxes driving businesses and jobs away, resulting in continued weak growth. What California’s middle and working classes need above all is broad, private-sector job growth—and that, fortunately, is a goal still well within reach. The Golden State may be run stupidly, but it retains enormous assets: its position on the Pacific Rim, large numbers of aspiring immigrants, unparalleled creative industries, fertile land, and a treasure trove of natural resources.

The most promising opportunity is in the contentious area of fossil-fuel energy, a mainstay of the state’s economy since the turn of the twentieth century. California still ranks as the nation’s fourth-largest oil-producing state. Traditional energy has long provided good jobs; nationally, the industry pays an average annual salary of $100,000. And elsewhere, from the Great Plains to eastern Ohio, an oil and gas boom is driving growth.

But California has thus far excluded itself from the party. Even as production surges in other parts of the country, California companies like Occidental Petroleum report diminishing oil production. The drop-off proves, some environmentalists say, that “peak oil” has been reached, but the evidence shows otherwise: the last few years have seen a fourfold increase in applications for drilling permits in California, largely because of the discovery of the massive Monterey shale deposits—containing a potential 15 billion barrels of oil—and of an estimated 10 billion barrels near Bakersfield. The real reason for the reduced production is that California has rejected most of the drilling applications since 2008. “I asked Jerry Brown about why California cannot come to grips with its huge hydrocarbon reserves,” recalls John Hofmeister, former president of Shell Oil’s U.S. operations. “After all, this could turn around the state. He answered that this is not logic, it’s California. This is simply not going to happen here.”

The anti-fossil-fuel stance, according to the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation, has placed some $1 billion in investment and 6,000 jobs on hold. The sense of wasted opportunity can be palpable. If you travel to Santa Maria, a hardscrabble town near the Monterey formation, you pass empty industrial parks and small, decaying shopping centers. As economist Watkins put it at a recent conference there: “If you guys were in Texas, you’d all be rich.”

California doesn’t even need to abandon its progressive tradition to narrow the class divide. Homebuilding, manufacturing, and warehousing could expand if regulatory burdens other than those associated with fighting climate change were merely modified—not repealed, but relaxed sufficiently to make it possible to do business, put people to work, and make a profit. New energy production could take place under strict regulatory oversight. Future industrial and middle-class suburban development could be tied to practical energy-conservation measures, such as promoting home-based businesses and better building standards. California’s agriculture industry—currently thriving, thanks to exports—could be less burdened by the constant threat of water cutbacks and new groundwater regulations.

Even from an environmental perspective, increased industrial growth in California might be a good thing. The state’s benign climate allows it to consume fossil-fuel energy far more efficiently than most states do, to say nothing of developing countries such as China. Keeping industry and middle-class jobs here may constitute a more intelligent ecological position than the prevailing green absolutism.

More important still is that a pro-growth strategy could help reverse California’s current feudalization. The same Public Policy Institute of California study shows that during the last broad-based economic boom, between 1993 and 2001, the 10th percentile of earners enjoyed stronger income growth than earners in the higher percentiles did. The lesson, which progressives once understood, is that upward mobility is best served by a growing economy. If they fail to remember that all-important fact, the greens and their progressive allies may soon have to place the California dream on their list of endangered species.

This piece originally appeared in The City Journal.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and contributing editor to the City Journal in New York. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, released in February, 2010.

Los Angeles aqueduct photo by BigStockPhoto.com.