Dennis Meyers is the Principal Economist at California’s Department of Finance. He has recently published two parts of what is promised to be a four-part series titled The Declinists are Wrong. He intends to convince us of “the fundamental strength of the Golden State’s dynamic and vibrant economy.”

I was going to wait until the entire series was complete before commenting, but part one and part two are so poorly argued that I feel compelled to respond now.

In part one, Meyers argues that California’s economy is strong because it is big. He points out that California represents about 12 percent of the United States population and is the ninth largest economy in the world.

This is, as Mr. Spock would say, highly illogical. It just doesn’t follow that just because you are big you will have a “dynamic and vibrant” economy. Instead, we have lots of counter examples. Great Britain was once large, wealthy, vigorous, and powerful. Not anymore.

Closer to home, we have Detroit. In 1950, Detroit’s population was 1.85 million, and it was America’s fourth largest city. Today, Detroit has a population of only 713,777. Its once-vigorous economy is not even a shadow of its former self. Its government is unable to even keep the lights on. It turns out that the lights do go off before the last person leaves.

In part two, Meyers argues the California is wealthy and this assures a prosperous future. This is, of course, the same logical fallacy as in part one. Detroit was also once one of America’s richest cities.

Meyers makes another mistake: He talks about average incomes. When it comes to incomes, averaging hides California’s real story, which is its increasing inequality and increasing poverty. California has two of America's poorest cities. Fresno, with a poverty rate of 30.2 percent, is the eighth poorest American city over 200,000 population. San Bernardino, in the same category, and with a poverty rate of 34.6 percent, is second only to Detroit.

One of the denialists’ favorite tactics is to find a data point where California does pretty well, and then argue that the selected data point is a reason for the state to do well. Call this a selective data bias. Of course, expanding from the specific to the general is a logical fallacy. This dog is brown therefore all dogs are brown.

Typically, venture capital is the selected data. A huge percentage of the nation’s venture capital is invested in California, no doubt about it. The problem is that the nation’s venture capital is not all that much. In 2011, California received 51 percent of the nation’s $28.76 billion venture capital net investment — $14.76 billion, which represents less than one percent of California’s almost $2 trillion economy. Almost all of it went to four counties in the Bay Area.

Meyers takes selective data analysis to a new zenith. He digs through California’s jobs data to find small sectors that are generating jobs at a faster rate in California than nationwide. For example, California's Computer and Electronic Production Sector (a sub-category of Durable Manufacturing) created jobs at a rate of 2.1 percent in 2010, compared to a national rate of 1.1 percent.

That’s all well and good, but over the past 12 months, California has lost durable manufacturing jobs. The growth that Meyers cites has only slowed California’s manufacturing jobs losses. Slowing decline is welcome, but it’s not a sign of imminent prosperity.

And he adds a nice touch discussing mining:

"The one high-wage sector in which national job gains outpaced those in California was Mining, which includes oil and natural gas production. There are several regions, such as Texas, that are blessed with generous deposits of these resources which California lacks. This advantage also shows up in Engineering Services employment…. The presence of healthy oil and natural gas resources typically generates demand for engineering consulting services related to exploration and extraction."

That’s just wrong. California has abundant oil and natural gas resources. In fact, recent California discoveries are roughly equivalent to the proven reserves of Nigeria, the world’s 10th-largest oil producer. We’ve chosen not to extract them. We’ve also chosen to no longer exploit California’s vast mineral resources.

Chris Thornberg, Beacon Economics founder and economist, recently came up with a novel argument to deny California’s decline. He says that since recent jobs data have been revised upward, “we are in full recovery mode and not looking back.” The problem here is that the jobs data were revised from terrible to merely dismal.

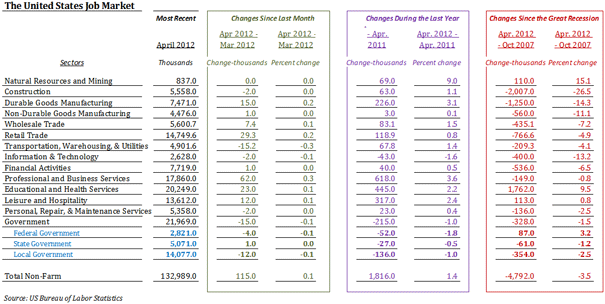

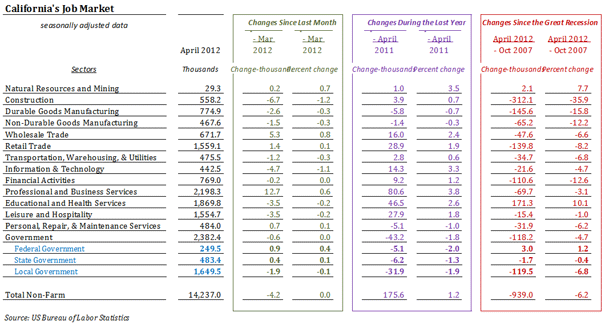

Look at the data. Below are two charts summarizing changes in jobs since the pre-recession peak. The first is the United States. California is the second. Both are pretty discouraging. Four and half years after the recession, the US is still down almost 5 million jobs. This represents about a 3.5 percent net decline. California, down almost a million jobs, is even worse — down a net 6.2 percent.

Job Changes From the Peak

California has also seen slower-than-US job gains over the past year. It is worse than that, though. California has lost jobs in durable manufacturing, non-durable manufacturing, and in the other services category, labeled as Personal, Repair, & Maintenance Services in the table. By contrast, the US only saw job losses in one sector over the past year, the information and technology sector.

The very recent news is worse. In March, the most recent month for which we have data, California lost jobs while the nation gained. And the number of declining sectors has expanded to include construction, durable and non-durable manufacturing, transportation, warehousing, utilities, education/health, and leisure/hospitality.

The signs of California’s weaknesses are all around us. With about 12 percent of the US population, we have about a third of the nation’s welfare recipients. It tops the nation in teen unemployment. Domestic migration has been negative for about two decades, after a century-and-a-half of being the destination for people from all over America.

California’s weakness is the result of California’s choices. It has chosen to be anti-oil and anti-gas, and to unilaterally implement the nation’s most restrictive environmental regulations. California has elected to impose the nation’s most restrictive regulatory regime on all businesses and an onerous tax system. In short, California has chosen to be anti-opportunity and to have a weak economy. The denialists have chosen not to see California’s decline.

Flickr Photo by Steve Rhodes: Jobless not Hopeless, Ask for my resume - Chris Stewart, Union Square, San Francisco 2009

Bill Watkins is a professor at California Lutheran University and runs the Center for Economic Research and Forecasting, which can be found at clucerf.org.

a collection of historical travel essays. His next book is Whistle-Stopping America.

a collection of historical travel essays. His next book is Whistle-Stopping America.