The blue team may have lost the political battle last year, but with the rapid fall of oil and commodity prices, they have temporarily gained the upper hand economically. Simultaneously, conditions have become more problematical for those interior states, notably Texas and North Dakota, that have benefited from the fossil fuel energy boom. And if the Obama administration gets its way, they are about to get tougher.

This can be seen in a series of actions, including new regulations from the EPAand the likely veto by the president of the Keystone pipeline, that will further slow the one sector of the economy that has been generating high-paid, blue collar employment. At the same time, housing continues to suffer, as incomes for the vast majority of the middle class have failed to recover from the 2008 crash.

Manufacturing, which had been gaining strength, also now faces its own challenges, in large part due to the soaring U.S. dollar, which makes exports more expensive. Amidst weakening demand in the rest of the world, many internationally-oriented firms such as United Technologies and IBM forecast slower sales. Low prices for oil and other commodities also threatens the resurgence of mainstream manufacturers such as Caterpillar, for whom the energy and metals boom has produced a surge in demand for their products.

Left largely unscathed, for now, have been the other, less tangible sectors of the economy, notably information technology, including media, and the financial sector, as well as health services. In sharp contrast to manufacturing, energy, and home-building, all of these sectors except health care are clustered in the high-cost, blue state economies along the West Coast and the Northeast. As long as the Fed continues to keep interest rates very low, and maintains its bond-buying binge, these largely ephemeral industries seem poised to appear ever more ascendant. No surprise then that one predictably Obama-friendly writer called the current economy “awesome” despite weak income growth and high levels of disengagement by the working class in the economy. If Wall Street and Silicon Valley are booming, what else can be wrong?

Should the whole economy become more bluish?

One consistent theme of blue-state pundits, such as Richard Florida, is that blue states and cities “are pioneering the new economic order that will determine our future.” In this assessment, the red states depend on an economy based on energy extraction, agriculture and suburban sprawl. By this logic, growing food for mass market consumers, building houses for the middle class, making cars, drilling for oil and gas—all things that occur in the red state backwaters—are intrinsically less important than the ideas of nerds of Silicon Valley, the financial engineers of Wall Street, and their scattered offspring around the country.

But here’s a little problem: these industries do not provide anything like the benefits that more traditional industries—manufacturing, energy, housing—give to the middle and working classes. In fact, since 2007, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the information and technology sectors have lost more than 337,000 jobs, in part as traditional media jobs get swallowed by the Internet. Even last year, which may well prove the height of the current boom, the information and technology industry created a net 2,000 jobs. And while social and on-line media may be expanding, having added 5,000 jobs over the last decade, traditional media lost ten times as many positions, according to Pew.

In contrast, energy has been a consistent job-gainer, adding more than 200,000 jobs during the same decade. And while manufacturing lost net jobs since 2007, it has been on a roll, last year adding more than 170,000 new positions. Construction, another sector hard hit in the recession, added 213,000 positions last year. The recovery of these industries has been critical to reducing unemployment and bringing the first glimmer of hope to many, particularly in the long suffering Great Lakes region.

These tangible industries seem to be largely irrelevant to deep blue economies. A prospective decline of energy jobs, for example, does not hurt places like California or New York, which depend heavily on other regions to do the dirty work. Overall, for example, California, despite its massive energy reserves, created merely 15,000 jobs since 2007, barely one-tenth as many as in Texas. Energy employment in key blue cities such as New York and San Francisco has remained stagnant, and actually declined in Boston.

Similarly, a possible slowdown in manufacturing—in part due to an inflated dollar, depressed international demand, and the loss of industrial jobs tied to energy—will affect different regions in varying degrees. Since 2009, the manufacturing renaissance has been strongly felt in traditional hubs like Detroit, Grand Rapids, and Louisville, as well as energy-charged places such as Houston and Oklahoma City. All saw manufacturing growth of 10 percent or more. Meanwhile New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, San Francisco, and Boston all lost industrial positions.

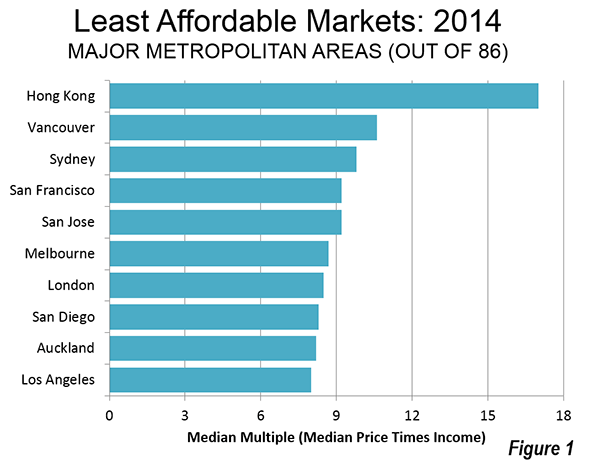

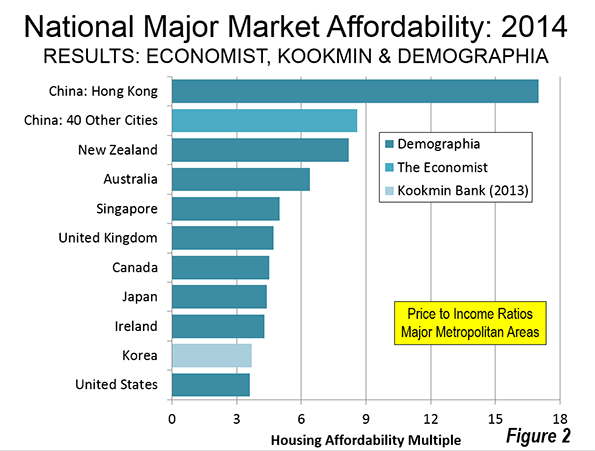

Finally, there remains the housing sector, a prime employer of blue collar workers and the prime source of asset accumulation for middle class families. Sparked by migration and income growth, construction growth has been generally stronger in Texas cities but far more sluggish in New York and California, where slower population growth and highly restrictive planning rules make it much tougher to build affordable homes or new communities. Last year at the height of the energy boom, Houston alone built more single family homes than the entire state of California.

If you think inequality is bad now …

The new ephemera-based economy thrills those who celebrate a brave new world led by intrepid tech oligarchs and Wall Street money-men. The oligarchs in these industries have gotten much, much richer during the current recovery, not only through stocks and IPOs, but also from ultra-inflated real estate in select regional areas, particularly New York City and coastal California. As economist George Stiglitz has noted, such inflation on land costs has been as pervasive an effect of Fed policy as anything else.

Even in Houston, some academics hail the impending “collapse of the oil industrial economy,” even as they urge city leaders to compete with places like San Francisco for the much ballyhooed “creative class.” Yet University of Houston economist Bill Gilmer notes that low energy prices are driving tens of billions of new investment at the port and on the industrial east side of the city. This growth, he suggests, may help offset some of the inevitable losses in the more white collar side of the energy complex.

The emergence of a new ephemera-led economy bodes very poorly for most Americans, and not just Texans or residents of North Dakota. The deindustrialized ephemera-dominated economy of Brooklyn, for example, has made some rich, but overall incomes have dropped over the last decade; roughly one in four Brooklynites, overwhelmingly black and Hispanic, lives in poverty. Similar patterns of increased racial segregation and middle class flight can be found in other post-industrial cities, including one-time powerhouse Chicago, where areas of concentrated poverty have expanded in recent years.

Nowhere is this clearer than in ephemera central: California. Once a manufacturing juggernaut and a beacon of middle class opportunity, the Golden States now suffers the worst level of poverty in the country. While Silicon Valley and its urban annex, San Francisco, have flourished, most of the state—from Los Angeles to the Inland regions—have done poorly, with unemployment rates 25 percent or higher than the national average. The ultra-“progressive” city now suffers the most accelerated increase in inequality in the country.

Similar trends have also transformed Silicon Valley, once a powerful manufacturing, product-producing center. As the blue collar and much of older middle management jobs have left, either for overseas or places like Texas or Utah, the Valley has lost much of its once egalitarian allure. San Jose, for example, has long been home to the nation’s largest homeless encampment. Black and Hispanic incomes in the Valley, notes Joint Venture Silicon Valley, have actually declined amidst the boom, as manufacturing and middle management jobs have disappeared, while many tech jobs are taken by predominately white and Asian younger workers, many of them imported “techno-coolies.”

In contrast, the recoveries in the middle part of the country have been, to date, more egalitarian, with incomes rising quickly among a broader number of workers. At the same time, minority incomes in cities such as Houston, Dallas, Miami, and Phoenix tend be far higher, when compared to the incomes of Anglos, than they do in places like San Francisco, New York, or Boston. In these opportunity cities, minority homeownership—a clear demarcation of middle income aspiration—is often twice as high as it is in the epicenters of the ephemeral economy.

To succeed in the future, America needs to run on all cylinders.

The cheerleaders of the ephemeral economy often point out that they represent the technological future of the country, and concern themselves little with the competitive position of the “production” economy—whether energy, agriculture, or manufacturing. They also seek to force the middle class into ever denser development, something not exactly aspirational for most people.

Nor is the current ephemera the key to new productivity growth. Social media may be fun, but it is not making America more competitive or particularly more productive (PDF). Yet there has been strong innovation in “production” sectors such as manufacturing, which alone accounts for roughly half (PDF) of all U.S. research and development.

What is frequently missed is that engineering covers a lot of different skills. To be sure the young programmers and digital artists are important contributors to the national economy. But so too are the many more engineers who work in more mundane fields such as geology, chemical, and civil engineering. Houston, for example, ranks second (PDF) behind San Jose in percentage of engineers in the workforce, followed by such unlikely areas as Dayton and Wichita. New York, on the other hand, has among the lowest percentage of engineers of major metropolitan areas.

To be sure, an aerospace engineer in Wichita is not likely to seem as glamorous as the youthful, urbanista app-developers so lovingly portrayed in the media. Yet these engineers are precisely the people, along with skilled workers, who keep the lights on, planes flying and cars going, and who put most of the food on people’s tables.

The dissonance between reality and perception is most pronounced in California. The state brags much about the state’s renewable sector to the ever gullible media. But in reality high subsidized solar and wind account for barely 10 percent ofelectrical production, with natural gas and coal, now mostly imported from points east, making up the vast majority. In terms of transportation fuels, the state has a96 percent dependence on fossil fuels, again large imported, despite the state’s vast reserves. Los Angeles, although literally sitting on oil, depends for 40 percent of its electricity on coal-fired power from the Intermountain West.

Equally critical, the now threatened resurgence of the industrial and energy sectors could reverse trends that have done more to strengthen the U.S. geopolitical situation than anything else in recent decades. Foreign dictators can easily restrict a Google, Facebook, or Twitter, or create locally-based alternatives; for all its self-importance, social media has posed no mortal danger to authoritarian countries. In contrast, the energy revolution has undermined some of the world’s most venal and dangerous regimes, from Saudi Arabia and Iran to Russia and Venezuela.

In no way do I suggest we don’t need the ephemeral sectors. Media, social and otherwise, remain important parts of the American economy, and testify to the country’s innovative and cultural edge. But these industries simply cannot drive broader based economic growth and opportunity. Part of the problem lies in the nature of these industries, centered largely in Silicon Valley and San Francisco, which require little in terms of blue collar workers. Another prime issue is that these areas can only import so many people from the rest of country due to extraordinary high housing costs.

Under current circumstances, the centers of the ephemeral economy such as New York or San Francisco cannot accommodate large numbers of upwardly mobile people, particularly families. These, for better or worse, have been vast gated communities that are too expensive, and too economically narrow, to accommodate most people, except those with either inherited money or elite educations. This is why Texas—which has created roughly eight times as many jobs as California since 2007 and has accounted for nearly one-third of all GDP growth since the crash—remains a beacon of opportunity, and the preferred place for migrants, a slot that used to belong to the Golden State.

As a country, we stand at the verge of a historical opportunity to assure U.S. preeminence by melding our resource/industrial economy with a tech-related economy. Our strength in ephemera can be melded with the power of a resource and industrial economy. In the process, we can choose widespread and distributed prosperity or accept a society with a few pockets of wealth—largely in expensive urban centers—surrounded by a downwardly mobile country.

The good news is America—alone among the world’s largest economies—has demonstrated it can master both the ephemeral and tangible economies. To thrive we need to have respect not for one, but for both.

This piece first appeared at The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

![]()

a collection of historical travel essays, and

a collection of historical travel essays, and