Perhaps nothing has more defined America and its promise than immigration. In the future, immigration and the consequent development of what Walt Whitman (1855: iv) called “a race of races” will remain one of the country’s greatest assets in the decades to come.

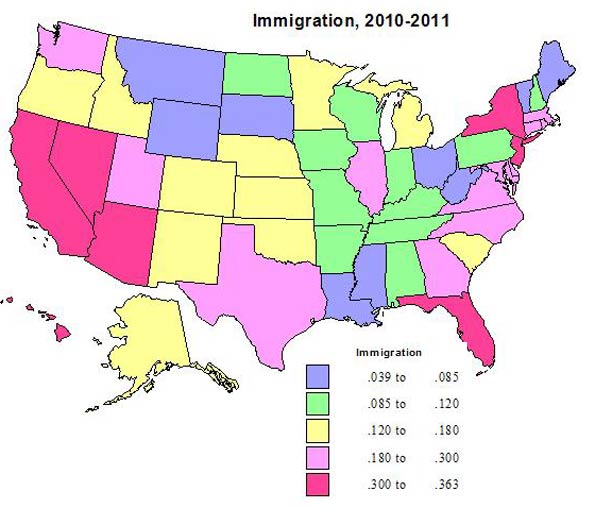

At a time when anti-immigrant fervor has been building, a number of states—including Arizona, Georgia, and Alabama—have enacted draconian laws aimed at apprehending undocumented immigrants. Those laws are widely seen even among legal immigrants and long-term residents as hostile to immigrants. Indeed, newcomers are already leaving those states. This Latino exodus has been happening in once-thriving neighborhoods in Gwinnett and Cobb counties in Georgia—as shown in business closures, arrest statistics, and declining church attendance—caused both by the economy and the increased immigration enforcement (Simmons 2010). Nationwide, there has been a declining number of unauthorized immigrants living in the United States, a decrease of 1 million from 2007 (Hoefer, Rytina, and Baker 2011).

These laws and other similar efforts could have long-term negative effects for many communities, particularly for local enterprises in sectors such as agriculture, construction, transportation, and hospitality, which are highly dependent on foreign labor. Other industries that would be negatively affected include the professional and related industries, as well as the service industry (Shapiro and Vellucci 2010).

But beyond specific industries, immigration may prove more important in the future than in the past. The three key elements behind this assessment are the global demographic slowdown, globalization of the world economy, and challenges to our own longterm economic and social sustainability. Immigration represents a key factor in determining whether the United States can avoid longterm stagnation and maintain its leadership role in the world economy. Overall we should be less concerned about too many newcomers than with the consequences of drastically reduced rates of immigration.

New Global Demographics

The developed world is entering an unprecedented era of largely unexpected demographic change. To the Baby Boomer generation, brought up on fears of overpopulation promoted in books such as Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, the idea of there being too few people seems almost absurd. Many xenophobes and anti-immigration activists still advocate a “national population policy” aimed at slowing population growth by strict limits on immigration.

Yet in sharp contrast to Ehrlich’s predictions, global population growth has not increased but slowed considerably over the past few decades. Global population growth rates of 2 percent in the 1960s have dropped to less than half that rate, and past projections of the number of earth’s human residents in 2000 overshot the mark by more than 200 million.

That pattern is likely to continue, with annual population growth rates declining to less than 0.8 percent by 2025, largely due to an unanticipated drop in birth rates in developing countries such as Mexico and Iran. Those declines can be attributed to increased urbanization, the education of women and their entrance into the workforce, and greater secularization. Close to half the world’s population, notes demographer Nicholas Eberstadt (2010), lives in countries with birth rates below the replacement level. Rather than out-of-control births, the world is experiencing a “fertility implosion.”

Overall what author Phil Longman (2010) calls a “gray tsunami” will be sweeping the planet, with more than half of all of the population growth coming from the number of people over 60 while only 6 percent will be from people under 30. The battle of the future, including in the developing world, will be to maintain large enough workforces required for the economic growth needed to care for the elderly (Longman 2011).

Those growth numbers could plunge further if slow economic growth, particularly in advanced countries, persuades couples to postpone having families, perhaps permanently. This factor may already have contributed to slow population growth in Europe and Japan, which have suffered low growth rates over the past two decades. In fact, the annual growth rate in the 2000s for eastern Europe was _0.1 percent and is expected to decline to _0.2 percent in the 2010s and _0.33 percent in the 2020s. For western Europe the same trend is projected—from 0.46 in the 2000s to 0.29 in the 2010s, and 0.18 in the 2020s. In the case of Japan, since 2010 the total population has begun to decline, with fewer births than deaths (U.S. Census Bureau 2011).

But even in better economic conditions, the prospect is for continued slowing and even reversal of population growth, particularly in the most advanced countries in East Asia and Europe, where rapid aging, dramatically reduced marriage rates and low birth rates are now the norm (The Economist 2011).

Today, among the major countries in the world, only the United States produces enough children to reach near replacement—a case of what demographer Eberstadt (2010) calls “demographic exceptionalism.”

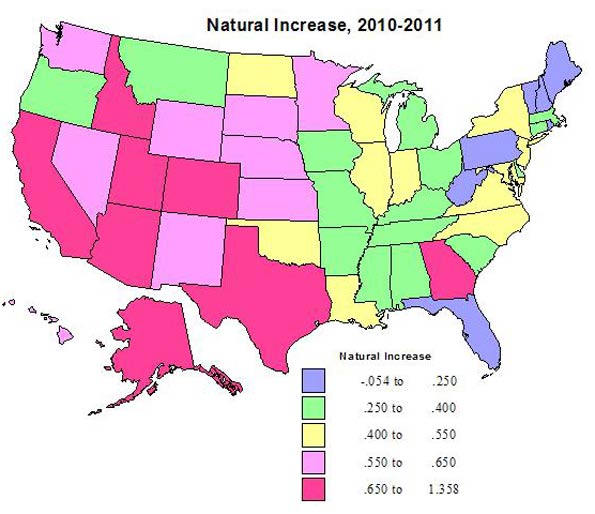

Although native-born Americans do not create enough children to sustain the population, immigrants and their offspring make up the difference. For example, the Mexican-American population grew more as a result of births (7.2 million) in the past decade than as a result of new immigrants (4.2 million) (Pew Hispanic Center 2011).

In the next several decades, the fate of Western countries may well depend on their ability to make social and economic room for people most of whose origins lie outside Europe (Rifkin 2004: 256_57; Eberstadt 2001: 123). Yet given Europe’s current considerable problems integrating its immigrants, particularly Muslims, the continent seems ill-disposed to open its doors further; Denmark and the Netherlands are considering measures to sharply restrict immigration (Feller 2005). Even more dire may be the situation in countries such as China, Japan, and Korea, which are culturally resistant to diversity.

In comparison, the U.S. record of healthy and sustained immigration marks a major competitive advantage. The largest immigrant population, Mexican American, is younger and has higher fertility rates than other groups. The median age of Mexican Americans in the United States is 25, compared to 30 for non-Mexican-origin Hispanics, 32 for blacks, 35 for Asians, and 41 for whites. The typical Mexican American woman has given birth to more children (2.5) than a similar aged non-Mexican Hispanic (1.9), black (2.0), white (1.8), or Asian (1.8) woman (Pew Hispanic Center 2011).

Mexican and other immigrants are one key reason why America boasts a fertility rate 50 percent higher than Russia, Germany, or Japan, and well above that of China, Italy, Singapore, Korea, and virtually all of eastern Europe (The Economist 2002; United Nations 2005; Longman 2004: 60). Consequently, it is widely believed America’s workforce will continue to grow even as that of Japan, Europe, Korea, and eventually even China will start to shrink. Between 2000 and 2050, for example, the U.S. workforce is projected to grow by over 40 percent, while that of China shrinks by 10 percent, the EU by 25 percent and, most remarkably, Japan’s by over 40 percent (U.S. Census Bureau International Database).

Over time the impact of an older population could prove ruinous to these economies both in terms of consumption and growth and perhaps more importantly in terms of their ability to support retirees.

By 2050, barely one in five Americans will be over 60 while the proportion in Japan, Germany, and Korea will be closer to two in five (Longman 2004: 53).

Lower birth rates in poorer countries such as Brazil can be seen as beneficial, offering significant short-term economic and social benefits (Gorney 2001). In advanced countries, however, a rapidly aging or decreasing population does not bode well for societal or economic health, whereas a still growing population offers the hope of expanding markets, new workers, and entrepreneurial innovation (Sheram and Soubbotina 2000).

Too Few Immigrants?

In public perception and in many state legislatures there has been a growing sense that the United States receives far too many immigrants. That view is particularly understandable during a period of deep economic pessimism and wrenching change. Yet in reality, under current conditions, the problem may soon be too little as opposed to too much immigration.

Although the foreign-born population in the United States grew by 10 million over the past decade, few have noted that immigration has entered into what could be a secular decline. Take, for example, illegal immigration, which is most noxious to many policymakers, particularly on the right. According to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS 2011), an estimated net 3 million undocumented immigrants entered the country in the five-year period between 2000 and 2004, but that number fell by two-thirds, to under 1 million between 2005 and 2009 (Hoefer, Rytina, and Baker 2011).

To some extent, stricter enforcement has been one reason for this drop-off (Cave 2011, Stevenson 2011). But a look at legal immigration also shows a decline. The number of Mexicans obtaining legal permanent resident status declined from the decade of the 1990s to 2000s by more than 1 million (2.76 million compared to 1.70 million), according to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS 2011). Indeed, since 2008 there has been a precipitous reduction in the number of naturalizations. In 2008 there were over 1 million naturalizations; in 2010 there were barely 600,000, a remarkable 40 percent drop (DHS 2011: Table 20).

The reduction in immigration and naturalization extend well beyond Mexico, which accounts for roughly 30 percent of all U.S. immigrants (Grieco and Trevelyan 2010). Asian naturalization rates, for example, have been dropping since the mid-2000s, and in 2010 fell to 250,000 compared to 330,000 in 2008, a 24 percent drop. Similar falloffs can be seen across America and Europe (65 percent drop for North America, 31 percent for South America, and 28 percent for Europe). In fact the only place from which naturalizations are on the rise appears to be Africa, with an 18 percent increase (DHS 2011: Table 21).

Why is this happening? One likely reason is that the world demographic slowdown has moved from advanced countries to traditional sources of immigrants such as China, India, Mexico, and the rest of Latin America. Mexico’s birth rate, for example, has declined from 6.8 children per woman in 1970 to roughly 2 children per woman in 2011 (The Economist 2010). Meanwhile, the number of Mexicans annually leaving Mexico for the United States declined from more than 1 million in 2006 to 404,000 in 2010, a 60 percent reduction (Pew Hispanic Center 2011).

This trend means that the number of future job seekers will be greatly diminished. In fact, in the 1990s Mexico was adding about 1 million potential job seekers annually. By 2007, the new potential job seekers declined to about 800,000 annually, and it is expected to drop to 300,000 by 2030, which will likely further slow Mexican immigration (Cave 2011).

A second major cause lies with the improved economy in many developing countries. In Mexico, employment and educational opportunities have improved since 2000. Both per capita gross domestic product and family income have climbed by more than 45 percent over the past 10 years. Not only are there fewer children to emigrate, but there is more opportunity for those who chose to remain (Magnini 2011).

These factors apply even more to immigration from Asia. Not only are birth rates lower there, but Asia also boasts some of the world’s fastest growing economies, from China and India to a host of smaller states in East Asia. As a result, immigrants (many of them well educated and entrepreneurial) who, in earlier years, might have felt the need to come to the United States now can find ample opportunities at home. Not surprisingly, naturalizations dropped 51 percent between 2008 and 2010 for immigrants from South Korea, 35 percent from Taiwan, 15 percent from China, and 7 percent from India (DHS 2011: Table 21).

The current economic crisis in the United States has contributed to the decision of Mexicans to stay in their country. That decision is particularly connected to troubles in housing and construction, industries that have been major sources of employment to both legal and illegal immigrants (Mataconis 2011). Hispanic immigrants have suffered a disproportionate share of job losses in the construction, agriculture, forestry, fishing, and manufacturing industries (Park 2009).

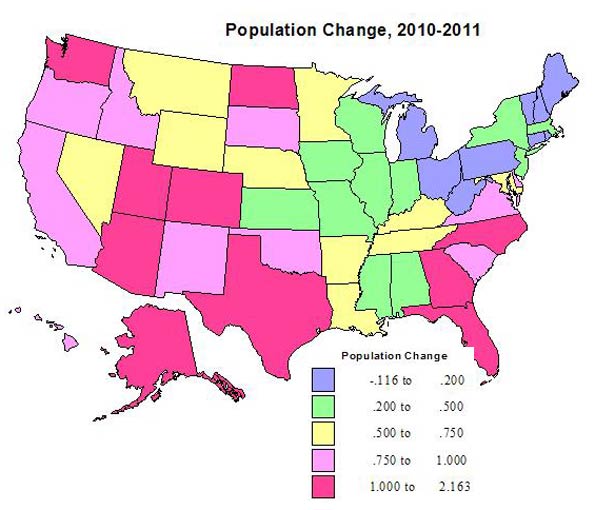

Over time that trend could create a labor shortage, notes John Skrentny, director of the Center for Comparative Immigration Studies at the University of California San Diego (Aguilera 2011). Already 40 states, reported in the last census, have fewer children than in 2000. Those that did not, such as Texas, can attribute much of their growth to immigrants and their offspring. “The new engines of growth in America’s population are Hispanics, Asians and other minorities,” notes demographer Bill Frey (Yen 2011).

Still the Multiracial Superpower?

A continued decline in immigration could undermine American competitiveness in other ways. Immigration has driven America’s successful evolution toward a society that will eventually be majority nonwhite, a factor that could prove critical in U.S. relations with developing nations, who will dominate the world’s economic growth for the foreseeable future (Cannadine 2002: 23; Kennedy 1993: 23).

Immigration represents much of what makes America different. This feature is particularly evident in relation to the Muslim world. In Europe, unemployment among immigrants from Muslim countries is often at least twice that of the native-born—and Muslims are deeply alienated. In contrast, American Muslims seem to be integrating with remarkably rapidity. More than four in five are registered to vote, a sure sign of civic involvement. Almost three-quarters say they have never been discriminated against (Manji 2007, MacFarquhar 2006, Valla 2007).

Such well-educated and entrepreneurial newcomers constitute a unique asset in a shifting global economy that relies on skilled workers and is increasingly tied to developing countries. Even today, the United States is by far the largest recipient of educated immigrants from these countries and attracts twice as many foreign students as any other country, with nearly two out of three coming from Asia (Docquier and Marfouk 2004).

Keeping a large portion of these immigrants should be a national goal and should not be difficult—given a proactive immigration policy, opportunities for advancement, better housing, political freedoms, and economic growth. Over the past two decades no country has proven as successful as the United States in retaining skilled foreign immigrants (Flora 2006; Sum, Harrington, and Khatiwada 2006; Anderson 2006).

By far the majority of America’s immigrants, both undocumented and legal, come from developing countries: China, India, Mexico, the Philippines, and the Middle East. Since roughly four in five immigrants come from nonwhite countries, by the early 2000s the majority of new workers entering the labor force were nonwhite. By 2039, due largely to immigrants and their offspring, the majority of working-age Americans will be nonwhite (Fraser 2004, Roberts 2008).

The role of America’s non-Western emigrants—Indian and Middle Eastern entrepreneurs, African intellectuals and scientists, Chinese technologists, and Mexican skilled workers—cannot be easily overestimated. Even as they return home, often as U.S. citizens, they retain strong familial and business ties to this country. Their ties here testify to America’s special ability to integrate all varieties of people into its society (Kurlantzick 2007: 9; Legrain 2007: 196).

The Entrepreneurial Force of 21st Century America

The greatest impact of immigration will be felt in the economy. Nowhere is this more critical than in the all-important entrepreneurial sphere. Immigrants by nature tend to be entrepreneurial as most come to America to find a better life for themselves and their families. The immigrant role in creating new business has been particularly critical during the current recession. According to a recent Kauffman Foundation report, the foreign-born were the one bright spot in the otherwise shell-shocked U.S. entrepreneurial sector. Overall, immigrants have boosted their share of new entrepreneurs from 13.4 percent in 1996 to nearly 30 percent in 2010 (Reedy 2011).

Immigrant commerce manifests itself most visibly in the proliferation of small stores, restaurants, food-processing businesses, garment factories, and trucking lines, as well as in high-tech and financial services. Immigrants are more likely to start a new business than native-born Americans. The number of self-employed immigrants has grown even in New York City, where the number of self-employed among the native-born has dropped (Bowles and Colton 2007).

Some of the country’s highest rates of entrepreneurship are found among immigrants from the Middle East, the countries of the former Soviet Union, Cuba, and Korea. These entrepreneurs can be found in a broad array of industries, including food and retailing as well as manufacturing and technology (Fairlie and Meyer 1996, Bowles and Colton 2007).

Perhaps most remarkable has been the movement of Asians into the technology industry. Between 1990 and 2005, immigrants mostly from the Chinese diaspora and from India started one of every four U.S. venture-backed public companies. In California, they account for a majority of such firms, particularly in technology (Anderson and Platzer 2006). Although many of these companies are small, a significant number have also become sizable, including Sun Microsystems, Yahoo, AST Research, and Solectron.

But it would be a mistake to see immigrant entrepreneurs as relevant largely to big cities and traditional technology hubs. Beginning in the 1990s, immigrants rapidly moved into regions once considered inhospitable to newcomers, particularly nonwhites—namely, the exurbs, Southeast, and Great Plains (Jacoby 2004: xxvii; Pickel and Clarke 2007).

Like other Americans, they are finding opportunities increasingly in regions where home prices are low and the business climate more conducive to entrepreneurs (Millman and Pinkston 2001, Spivak 2010). Many of the areas with the rapidly growing entrepreneurial classes among minorities—places like Atlanta, Nashville, Houston, and Dallas—are regions with diffuse, multipolar and heavily suburbanized land patterns. The strip mall, much detested among urban aesthetes and planners, often serves as “the immigrants’ friend,” in the words of Houston architect Tim Cisneros (Kotkin 2011).

Policy Prescriptions: Sustaining and Reforming the American Model

Given their contributions to our overall economic and demographic vitality, the current downturn in U.S. immigration should be a major concern to American policymakers. Although steps to curb illegal immigration may well be justified, the United States needs to start devising policies that encourage legal immigrants to come here and stay. This is particularly true for skilled and entrepreneurial newcomers.

Policymakers need to think much more about what happens to these potential immigrants. If there is a notion that America is not welcoming for newcomers, we could move toward a paradigm in which people come to the United States for relatively a brief stay, then head back home once they have achieved their educational or career goals—something already occurring with educated migrants, and even citizens, from booming economies such as China and India (Wadwha 2009). If this pattern becomes predominant, America would lose much of its competitive edge and its claims to still being an “exceptional” country.

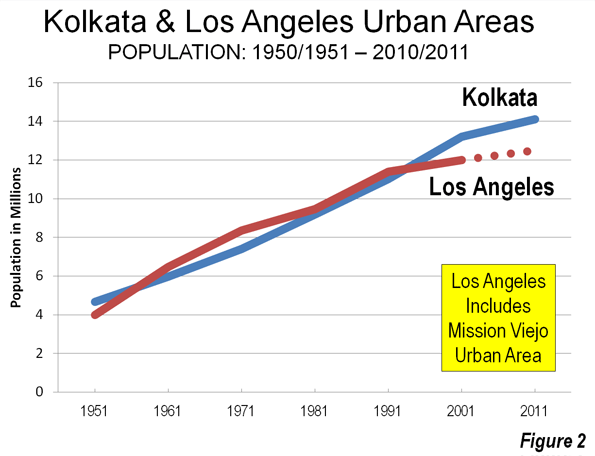

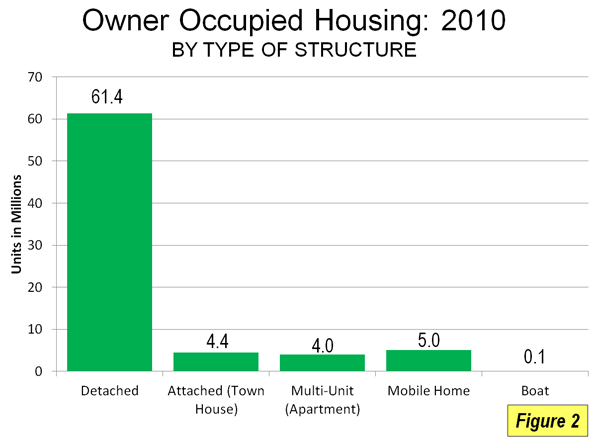

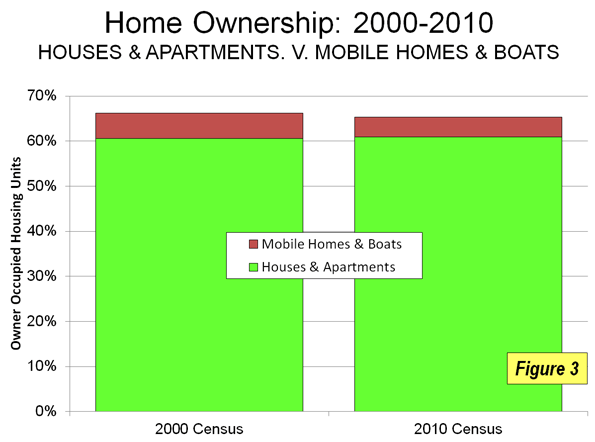

Economic growth is a prerequisite for many things, and continued strong immigration is one of them. But certainly more can be done to encourage college and graduate school students to become citizens. The United States should make efforts to keep entrepreneurs and all kinds of skilled workers, whom the country will need, particularly as the Baby Boom generation retires. The current recession has had a devastating effect on the long-term finances of Social Security and Medicare, now expected to run out of funds earlier than forecasted. This will affect the 78 million Baby Boomers retiring over the next two decades at a time when immigrants will play key roles in the U.S. economy as taxpayers, workers, consumers, and homebuyers (Ewing 2009).

Ultimately how America approaches immigration will have much to do with future development. We could turn inward (Hanson 2002; Huntington 1996: 204–06), hoping to salvage the older notions of an Anglo-Saxon national identity from ethnic encroachment by those who, in Pat Buchanan’s phrase, are not “melting and reforming” (Buchanan 2002: 12). Or we could follow the welfare state model of Europe, as many on the left prefer, becoming a permanently slow growth country with a rapidly aging population.

Neither of these scenarios is worthy of America. Our great genius as a country has been in our ability to integrate newcomers culturally as well as economically. Within a generation or two the overwhelming majority of Latinos lose their primary allegiance to their mother country and 97 percent consider America their home country (Winograd and Hais 2008: 95; Preston 2007b). They also embrace English—only 7 percent of second-generation Californian Latinos speak Spanish as their primary language (Hakimzadeh and Cohen 2007, Preston 2007a). Latinos also represent a growing portion of the U.S. military, hardly a sign of disaffection from the national culture (Rodriguez 2004, Porter 2002).

If attitudes harden against immigration, America will sacrifice much of its demographic and cultural uniqueness. We would also suffer the loss of a major source of entrepreneurial growth and innovation.

Essentially, the United States must remain an open economy and an open society if it wishes to retain its standing as the “land of the free.” A rational immigration policy would work against a scenario of rapid aging, stagnant population growth, labor shortages, and declining entrepreneurship, which are likely to afflict Europe and Asia. By remaining the world’s leading immigrant country, America would assure its future as the world’s beacon of liberty and prosperity.

This piece originally appeared in The Cato Journal..

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and contributing editor to the City Journal in New York. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, released in February, 2010. Erika Ozuna is a Research

Fellow at Pepperdine University.

Photo from BigStockPhoto.com.

References

Aguilera, E. (2011) “Illegal Immigration from Mexico Continues Decline.” Sign On San Diego. Available at www.signonsandiego.com/news/2011/jul/07/illegal-immigration-mexico-conti....

Anderson, K. W. (2006) “A Decline in Foreign Students Is Reversed.” New York Times (13 November).

Anderson, S., and Platzer, M. (2006) “American Made: The Impact of Immigrant Entrepreneurs on U.S. Competitiveness.” Arlington, Va.: National Venture Capital Association. Available at www.nvca.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=254&Itemid=103.

Bowles, J., and Colton, T. (2007) “A World of Opportunity.” New York: Center for an Urban Future (February). Available at www.nycfuture.org/images_pdfs/pdfs/IE-final.pdf.

Buchanan, P. (2002) The Death of the West: How Dying Populations and Immigrant Invasions Imperil Our Country and Civilization.New York: Thomas Dunne.

Cannadine, D. (2002) Ornamentalism: How the British Saw Their Empire. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cave, D. (2011) “Better Lives for Mexicans Cut Allure of Going North.” New York Times (6 July).

Cohn, D., and Passel, J. S. (2009) “Mexican Immigrants: How Many Come? How Many Leave?” Pew Hispanic Center (22 July).

Docquier, F., and Marfouk, A. (2004) “Measuring the International Mobility of Skilled Workers (1990–2000).” Policy Research Working Paper No. 3381. Washington: World Bank.

Eberstadt, N. (2001) “The Population Implosion.” Foreign Policy (March/April).

(2010) “The Demographic Future: What Population Growth—and Decline—Means for the Global Economy.” Foreign Policy (November/December).

The Economist (2002) “Five Hundred Million Americans.” The

Economist (22 August).

(2010) “Mexico’s Population: A Falling Birth Rate, and What It Means.” The Economist (22 April).

(2011) “Asia’s Lonely Hearts.” The Economist (20 August).

Ewing, W. (2009) “Immigrants Could Soften Effects of Baby Boomer Retirement.” ImmigrationImpact.com (14 May). Available at http://immigrationimpact.com/2009/05/14/immigrantscould-soften-effects-o....

Fairlie, R. W., and Meyer, B. D. (1996) “Ethnic and Racial Self-Employment: Differences and Possible Explanations.” Journal of Human Resources 31(4): 757–93.

Feller, B. (2005) “U.S. Immigrants Lag Behind in School, but Gaps Are Bigger in Other Nations.” Associated Press (15 May).

Flora, C. B., (2006) “Immigrants as Assets.” Rural Development News 28 (3). Ames, Iowa: North Central Regional Center forRural Development, Iowa State University.

Fraser, N. (2004) “The New Americans.” BBC News (2 April).

![]()