Blessed by Pope Francis, the drive to wipe out fossil fuels, notes activist Bill McKibben, now has “the wind in its sails.” Setting aside the bizarre alliance of the Roman Catholic Church with secularists such as McKibben, who favor severe limits of family size as an environmental imperative, this is a potentially transformational moment.

Simply put, the cultural and foreign policy issues that have defined U.S. politics for the past have century are increasingly subsumed by a divide over climate and energy policy. Progressive pundits increasinglyenvision the 2016 presidential election as a “last chance,” as one activist phrased it, to stop “climate change catastrophe.” As this agenda gets ever more radical, the prominence of climate change in the election will grow ever more obvious.

The key here is that the green left increasingly does not want to limit or change the mix of fossil fuels, but eliminate them entirely, the faster the better. The progressive website Common Dreams, for example, proposes eliminating fossil fuels within five or six years in order to assure “reasonable margin of safety for the world.”

This new militancy is a break from the recent past, when many greens embraced natural gas and nuclear power as practical, medium-term means to slow and even reverse greenhouse gas growth. But the environmental juggernaut, deeply entrenched within the federal bureaucracy and pushed by a president with seemingly limitless authority, is committed increasing to the systematic destruction of one of the country’s most important, and high-paying, industries. One goal is to demonize fossil fuel producers along the lines of the tobacco industry.

The pope’s intervention has bolstered the tendency within the environmental movement not to allow any challenge to its own version of infallibility. This, despite discrepancies between some models of climate change and what has actually taken place.

As we have moved from a rational discussion of the issue toward an increasingly dogmatic agenda, we have lost sight of more pragmatic, and less economically painful, ways to reduce greenhouse gases through methods such as conservation, the substitution of natural gas for coal, and a re-embrace of nuclear power. As the Breakthrough Institute has shown, most reductions in greenhouse gases in the United States have not come from subsidized renewable energy sources but instead from improved efficiency and the rise of natural gas at the expense of coal. Overall, solar and wind, the favorites of the greens, account for barely 1.35 percent of the world’s energy.

The Breakthrough Institute’s pragmatism intends to create a middle ground between the left, which demonizes even the slightest criticism of green policy dogma, and the right, which equally mistakenly dismisses climate change as essentially a fabrication. But with the extremes in control of the debate, we can expect next year to mainly hear divisive discourse instead of solutions.

The Geography of Energy

In some parts of the country, most notably the Northeast and the West Coast, the imperatives of climate change demand the destruction of the fossil fuel industry. In others, those that depend the most on low-cost energy, the attack on fossil fuels represents a moral threat to local economies, jobs and well-being. The battleground will be in the Great Lakes, arguably the most critical region for the next election. Contrary to its sad sack image, the economy there has been on the rebound for years. Virtually every Great Lakes state except Illinois now enjoys unemployment rates below the national average. Several, led by the Dakotas, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Iowa, boast job rates that are among the nation’s highest.

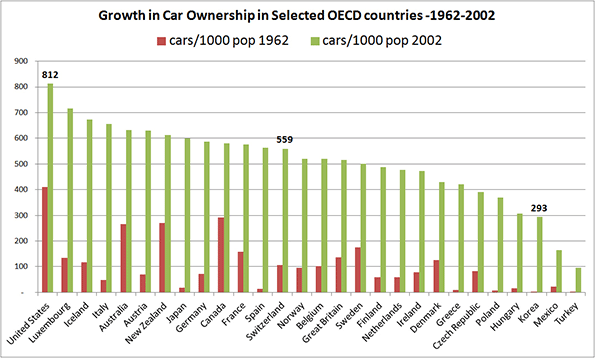

Three key factors are propelling this comeback: an energy boom, a resulting jump in manufacturing, and relatively low housing costs. Energy firms have been a major source of new work for industrial firms, and lower electricity costs have provided U.S. manufacturers with an energy price advantage over European and Asian firms. German electricity prices, a result of their “green” energy policies, are almost three times the average of those in the United States.

The administration’s directive to all but ban coal could be problematic for many Midwest states, including several—Iowa, Kansas, Ohio, Illinois, Minnesota and Indiana—that rank among those most reliant on coal for electricity. Not surprisingly, much of the opposition to the EPA’s decrees come from Heartland states such as Oklahoma, Indiana, and Michigan.

Politically, the energy-rich states running from Texas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana up to the Dakotas may be all but lost to the Democrats. Before the decline in oil prices, these areas enjoyed a gusher in energy jobs, providing high wage employment (roughly $100,000 annually) that exceeds compensation for information, professional services, or manufacturing. Due largely to energy, they have enjoyed the highest jobs growth since 2007 and were among the first states to gain back the jobs lost in the recession.

In contrast, the areas that form the solid base of the progressives—basically the Northeast and the West Coast—have an increasingly small stake in fossil fuel industries. California, which has the fifth largest oil reserves among the states, has basically decided to abandon the industry, gradually pushing the remnants of what was once a thriving sector out of the state.

For the most part, with the notable exception of Pennsylvania, Northeastern states have little in the way of fossil fuels, and have gradually been eliminating much of their manufacturing base for over a half century. Nor do they have much need for electricity for industry as they continue to deindustrialize. Manufacturing accounts for barely 5 percent of state domestic product in New York and 8 percent in California—but 19 percent in Michigan and 30 percent in Indiana.

Rise of the Climate-Industrial Complex

Climate activists such as hedge fund billionaire Tom Steyer increasingly couch their policies on theological grounds, one reason why the pope’s intervention was so timely. Stark self-interest is also at work. Many of the Silicon Valley and Wall Street supporters of green policies have been among those most anxious to capitalize on big oil’s demise.

This includes cash-rich firms such as Apple, as well as many high-tech financiers and venture capitalists. Some of the biggest new fortunes, notably that of Elon Musk, are largely the creatures of subsidies. Neither SolarCity nor Tesla would be so attractive—and might even not exist—without generous handouts from taxpayers.

In contrast to traditional manufacturers, capitalists like Musk have a well-developed interest in taking advantage of the most draconian energy legislation. Other tech figures, including top executives atGoogle, have benefited from government-subsidized renewable energy schemes, including a remarkably inefficient and expensive solar project that has obliterated a huge part of the Mojave Desert.

No surprise, then, that the crony capitalists of Silicon Valley and their Wall Street financiers have emerged as primary funders of the green left. Much like the oil firms that help finance Republicans, particularly those who are climate change skeptics, the new oligarchs have solid business reasons to embrace the pontiff’s environmental dogma, though they seem unlikely to follow his admonitions to eschew corporate greed.

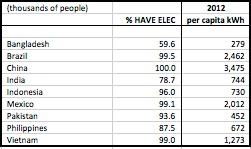

Ironically, the new militancy among greens is likely to hurt most the poor and working class with whom Pope Francis takes pains to identify. A rapid ban on fossil fuels in the developing world would hurt efforts to increase access to electricity. Today, some 1.3 billion people are off the grid, and not by choice. In sub-Saharan Africa, where much of the world’s population growth is expected to take place, roughlytwo-thirds of the population lacks regular access to electricity.

As Bjorn Lomborg has pointed out, whatever the negative effects of climate change on the poor, the impact of no electricity and poor sanitation are infinitely greater. Climate change policies, he notes, are an inefficient way to accomplish such things as reducing malaria; the Kyoto Protocol’s carbon cuts could save 1,400 malaria deaths for about $180 billion a year. More traditional approaches could save 300,000 people for about $500 million year.

Greens seem to have little idea what the poor want or need. When asked, people in developing countries prioritize such things as education, health care, job opportunities and better food; climate change ranked 16th—dead last on the list—according to a UN survey.

But the green gentry retain their catechisms. Prince Charles embraces the “intuitive grammar” of ultra-dense slums such as Mumbai’s Dharavi, which, he claims, have perfected more “durable ways of living” than those in the suburbanized West.San Francisco’s Friends of the Earth similarly applauds slum-dwellers as an “inspiration” for the low-carbon urban future, while Stewart Brand openly endorses the notion, “Save the Slums,” because they will save the planet.

Needless to say, it’s unlikely these apostles of urban squalor would want their children to live like that and it is absurd to suppose that leaders of such emerging powers as India and China have any intention of giving up on their gains in reducing poverty. We cannot expect they will accommodate the passions of wealthy Westerners at the expense of their own people.

A War on the Western Working Class?

Those most likely to pay for the new green agenda will be middle- and working-class populations in what are now rich countries. Germany spends hundreds of billions of dollars on solar panels and wind turbines that provide only an unreliable 15 percent of its electricity and 3 percent of its total energy. German consumers pay three times more for electricity than the average American. It’s so bad that Germans have added a new term to the language: “energy poverty.”

Perhaps the best test case for the impact of draconian climate policies is in my adopted home state of California. Here, high energy costs brought about by renewable mandates have devastated manufacturing growth and boosted electric bills, particularly in the poorer, and hotter, inland areas. Asone recent study found, the summer electrical bills in rich, liberal Marin come to $250 monthly while in impoverished Madera, the average is twice as high.

Of course, energy policy is just one of the things raising poverty in a state where many of the world’s greatest fortunes are being minted. But it’s part of a climate change-driven agenda that is also somewhat responsible for the state’s absurdly high housing costs by consciously limiting affordable suburban growth. Overall, nearly a quarter of Californians live in poverty, the highest percentage of any state, including Mississippi, and, according to a recent United Way study, close to one in three are barely able to pay their bills.

With the blessings of the pope and broad support in the media, few Democrats are likely to stand up against the green policies. Hillary Clinton’s shift against the Keystone XL Pipeline, despite strong union support for the project, shows that she is willing to trade blue-collar workers in the Heartland for the approval of the coastal gentry, among whom climate change has acquired something of a religious aspect. “Whether it’s eating vegetarian or wearing organic eye shadow, we're all shopping for absolution,” observes Daniel Engber in Slate.

Ultimately Democrats will embrace the determined attempt by President Obama to secure his “legacy” as the great calmer of the Earth’s climate. Yet there’s some question how effective these policies will prove. Invariably, efforts will follow to silence those skeptical of the current course, particularly regarding the economic impact on working-class voters. In California, Steyer and his allies have worked overtime to suppress any potential dissent from politicians who hail from the largely Latino, blue-collar districts hit most directly by these policies.

Despite a massive investment in Latino “grassroots” front groups, as well as politicians, this effort is not foolproof. This month a handful of largely Latino and inland Democrats, some of them backed by the state’s residual energy industry, killed Jerry Brown’s attempt to force a 50 percent reduction in fossil fuel use by 2030, a measure that would have allowed the state impose gas rationing.

To be sure, this rebellion may prove short-lived, as state regulators now seem determined to impose by decree what could not even make it through the state’s Democratic-dominated legislature. Steyer loyalists such as State Senate President Kevin de Leon will continue to mollify his impoverished constituents–nearly half of all households in his district earn less than $34,000 a year—with handouts from “cap and trade funds” and the ever illusive chimera of “green jobs.”

In truth, if anyone has benefited from green policies and subsidies, it’s been the well-off.

They are the ones who benefit from subsidized solar, electric vehicles, and fuel-efficient cars; a recent UC Berkeley study found the top fifth of households received 60 percent of these wealth transfers, compared to barely 10 percent of those in the bottom quintile. Generally speaking, barrio residents don’t drive $100,000 Teslas.

So will climate change be an effective issue for the Democrats next year? There is room for skepticism. In 2014 Steyer and his acolytes spent some $85 million on “green” candidates, only to fail impressively. Geography and class work against their efforts, driving longtime working and middle-class Democrats, driving voters in places like Appalachia, the Gulf Coast and some areas of the Great Lakes increasingly out of the Democratic Party.

It is not even certain that Millennials, faced with diminishing prospects for good jobs and home ownership, will prove reliable backers of a draconian climate agenda. One recent survey suggested that young voters are actually less likely to identify as “environmentalist” than previous generations.

Like extreme social conservatism on the right, climate change thrills the coastal “base” of the Democratic Party, but threatens to lose support from other parts of the electorate. Despite the duet of hosannas of both the hyper-secular media and the Bishop of Rome, a policy that seeks, at base, to reduce living standards may well not prove politically sustainable.

This piece originally appeared at Real Clear Politics.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is also executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is also author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Midwest drilling rig photo by Bigstock.

![]()

Residents play shuffleboard at Limetree Park in Bonita Springs, Florida. Steve Nesius/Reuters

Residents play shuffleboard at Limetree Park in Bonita Springs, Florida. Steve Nesius/Reuters