Seven years after the last housing debacle devastated the world economy, we may be on the verge of another, albeit different, bubble. If the last real estate collapse was created due to insanely easy lending policies aimed at the middle and working classes, the current one has its roots largely in a regime of cheap money married to policies of planners who believe that they can shape the urban future from above.

This time, the potential property blowout has roots in large part outside the United States. Many of China’s current problems, in fact, can be traced in part to its unhealthy inflation of real estate values spurred by a drive to increase urbanization and density. Last year, The Economist estimated median home price to median income of nearly 20 in Shenzhen, 17 in Hong Kong, and more than 15 in Beijing, between 50 percent and 100 percent higher than ultra-expensive places (PDF) like San Francisco, Vancouver, or Sydney.

At the same time, China’s response to these soaring prices has been to limit demand, but there’s little effort to liberalize land use that would allow for more affordable, less congested housing.

This emphasis on high-density development also threatens the country’s demographic future. Fertility rates in Shanghai and Beijing, notes Singapore-based demographer Gavin Jones (PDF), are already among the lowest found anywhere in the world, as low as one-third the necessary rate to replace their population. Jones’s research has shown an association between higher density living and far below replacement fertility rates.

As a highpoint in social engineering, a whole new dense city (Kangbashi) has been constructed by the Ordos, Inner Mongolia city government, in the middle of nowhere, growing, but still apparently mainly vacant.

The key here is not so much planning, per se, but planning in a manner that ignores the aspirations of people. Americans no more want to live stacked in boxes in the middle of nowhere than do their Chinese counterparts. America’s public housing may have been a notable disaster, but many private-sector-led planned developments have been remarkably successful. What works is planning that matches people’s aspirations, like those developments made by such giants as the late Bill Simon, who died Monday, in Reston, Virginia. But Simon’s development was not unique. Valencia and Irvine in southern California as well as the Woodlands and Cinco Ranch on the fringes of Houston have continued to thrive, and generally outperform their less planned alternatives.

Catching China’s Cold

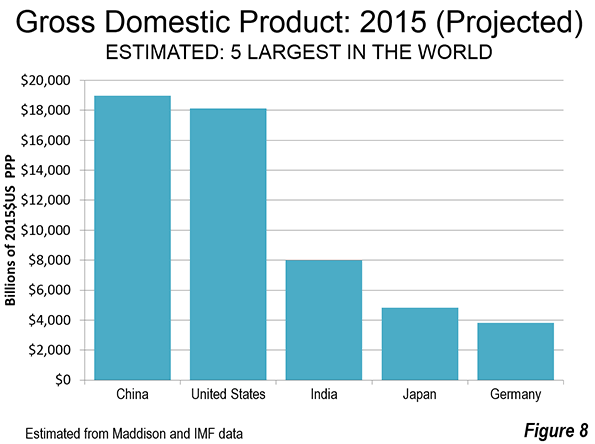

For the first time in a century, America may not be the source of the next “global recession;” that honor, so to speak, notes Morgan Stanley’s Ruchir Sharma, could well go to China. The country’s sky high real estate prices—and the prospect of their fall—will mean far more to the world than the recent widely ballyhooed downturn in the country’s stock markets. In reality, relatively few Chinese actually participate in equities. Only one in 30 Chinese owns stock. Investment in property is by far the favorite means by which affluent Chinese invest in the future.

This obsession with property is now being felt around the world. Real estate and hospitality, mostly hotels, accounted for 65 percent of China’s $6.4 billion investment in the US in the first half of 2015. This has been a major part of theoutflow of capital from China, which, at least until recently, has been accelerated by the perception of a weakening economy. Now the government appears ready to impose greater restrictions on private overseas investment, something that is already noted among real estate insiders in California. A devalued yuan, a sure sign of a weakening economy, also means Chinese investors will have less to spend in dollar terms.

Nowhere will this be more keenly felt than in countries like Australia, which has been a primary recipient of Chinese flight capital as well as immigration. Chinese students, as well as investors, have been critical to boosting the prices of Australian property, and losing their dollars could cause what some see as an impending crash in multi-family apartment across Australia. Census authorities in Australia indicate that mainland Chinese represent the third largest foreign-born segment of the population, trailing only the United Kingdom and New Zealand, long the principal contributors of overseas immigrants.

Making matter worse

The blame for the pending Australian meltdown however comes not just from China, but from the policies embraced by most of Australia’s planning authorities. Despite the fact that barely one-quarter of 1 percent of the country’s land is occupied, these authorities insist on promoting high-density development, even in old attractive suburbs. The result has been soaring prices for single-family homes, which, in Australia as elsewhere, are far more popular than the high-density housing preferred by planners. Upwards of 90 percent of people surveyed felt it was worthwhile to buy a house. This was marked particularly among people with children.

This disconnect between people and planners has turned Australia, a country of boundless spaces, into a nation with some of the most expensive cities in the world. Remarkably, Sydney is more expensive than virtually any American city and Melbourne is not far behind. Even middle-of-nowhere Adelaide, in the country’s temperate south, has housing costs, relative to income, of much larger and infinitely more consequential Seattle.

Australia is not alone in suffering the potentially lethal combination of planning orthodoxy and dependence on Chinese investment—this toxic mash up also applies to Canadian cities such as Toronto and Vancouver, which have imbibed the high density mantra, producing home prices well above those of most North American cities. Like Australians, the vast majority of Canadians prefer single-family houses. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has noted that Canada’s house prices have risen faster in recent years than those in any other high-income nation.

American realities

Traditionally, planning in the United States was liberal in the classical sense, that is, responsive to market forces. But increasingly, particularly during the Obama years, state planning agencies, notably in California, and the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) have embraced a largely anti-suburban, pro-density agenda. In 2010, HUD Secretary Shaun Donovan, pointing to foreclosures in suburban Phoenix, claimed that the die was already cast: "we’ve reached the limits of suburban development,” Donovan claimed. “People are beginning to vote with their feet and come back to the central cities.”

In embracing density as a preferred national policy, HUD is now following a path blazed earlier by planners in England, China, the former Soviet Bloc, and a handful of U.S. metropolitan areas.

Alexei Gutnov, one of the authors of the book The Ideal Communist City,acknowledged that in suburban development “ideal conditions for rest and privacy are offered by the individual house situated in the midst of nature.” But Gutnov feared that such housing might lead the citizen to “separate himself from others, rest, sleep, and live his family life,” which would make it harder for the state to steer him to the proper “cultural options.”

Socialist planning led to few Levittowns, but such mass and affordable housing flourished in capitalist America—albeit to the horror of many planners, academics, urban boosters, and inner city real estate developers.

Yet roughly 80 percent of Americans prefer the sort of single family housing found primarily in suburbia, according to a 2011 study conducted by the National Association of Realtors and Smart Growth America. Among home-owning households, apartment style dwellings (multi-family, including high rise condominiums) are the fourth most popular type of housing (5.3 percent), following detached (82 percent), mobile homes (6.4 percent), and attached or townhomes (5.7 percent). Only boats, RVs, etc. have less of the market, at 0.1 percent, according to the newly released 2014 American Community Survey.

Even in the Portland metropolitan area, where smart growth policy is perhaps the most entrenched in the United States, a public opinion research report (PDF) co-sponsored by the agency managing the land use regulation system, found that 80 percent of respondents would prefer a detached house.

Yet, like Soviet planners and their Chinese counterparts, our political elite and the planning apparat seem to care little about preferences, and have sought to limit single-family homes through regulations. This is most evident in California, notably its coastal areas, where house prices and rents have risen to hitherto stratospheric levels.

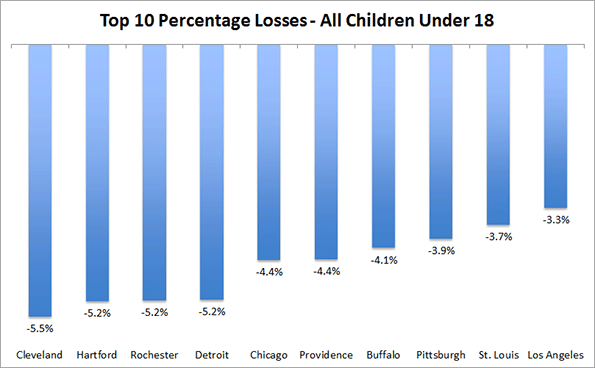

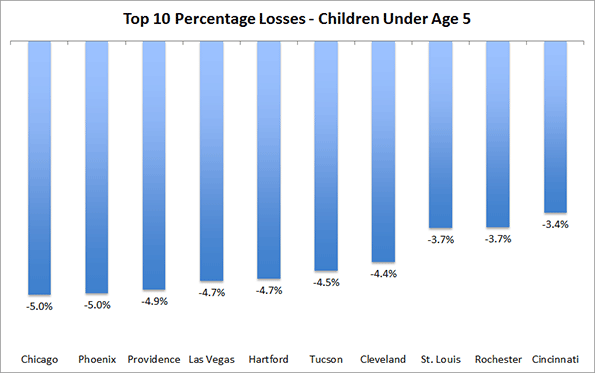

The losers here include younger middle and working class families. Given the regulatory cost, developers have a strong incentive to build homes predominately for the affluent; the era of the Levittown-style “starter home”, which would particularly benefit younger families, is all but defunct. Spurred by the current, highly unequal recovery, these patterns can be seen elsewhere, with a sharp drop in middle income housing affordability while the market shifts towards luxury houses.

These distortions in the market have been exacerbated by rising demand fromChinese buyers, which tends to concentrate at the luxury end of the market. Decreasing middle income housing supply has driven declining affordability for both renters and owners for a decade or more. Overall, U.S. housing production dropped not only since the 2007 recession but also by almost a quarter between 2011 and 2015. In California, production has fallen so far that one Texas metropolitan area, Houston, produced nearly as many new single-family homes in 2014 as the entire state of California.

The resultant boost in housing prices has worked its way into rents, too, largely by forcing buyers into the apartment market, and driving up rental rates to the largest share of income in modern U.S. history. In part this is due to a still weak economy that is generating little in the way of income gains; overall housing prices have been rising by more than twice that of incomes. Since 1990 renters’ income has been stagnant, while inflation-adjusted rents have soared 14.7 percent.

This situation, of course, is most severe in the highest priced markets. In New York, Los Angeles, Miami, and San Francisco, for example, renters spend 40 percent of their income on rent, well above the national average of less than 30 percent. In each of these markets there have been strong income adjusted increases relative to historic averages. In New York, rents increased by 50 percent between 2010 and 2015, while incomes for renters between 25 and 44 grew by just 8 percent.

One critical point: high density does not, as is commonly claimed by urban containment advocates, help solve the affordability issue. High density housing is far more expensive to build than single family or townhouse developments. Gerard Milder (PDF), the academic director at the Center for Real Estate at Portland State University, notes that a high rise of more than five stories costs nearly three times as much to build as a garden apartment. An analysis of costs in the San Francisco Bay Area found townhome developments can cost up to double that of detached houses per square foot (excluding land costs) and units in high-rise condominium buildings can cost up to 7.5 times as much. Not surprising, we now face an impending surplus of expensive, multi-family units in places where single-family housing is preferred by most and affordable housing is a dire necessity for many others.

The Shape of the Next Bust: The Planners’ Recession

The new real estate bust will be markedly different from the last one. In the last bubble, there was a surfeit of cheap capital loaned, often without adequate financials, to working and middle class people. The results were particularly harsh in places where strong urban containment (“smart growth”) policies were in effect—notably California, Arizona and Florida—and prices elevated as a result. In contrast more liberal markets, notably Texas, suffered far less while Florida has since repealed its urban containment requirements.

Today’s emerging potential bubble is driven in large part by low interest rates and a new post—TARP financial structure, anchored by ultra-low interest rates, which favor wealthy investors, including those from China and other capital exporting countries. This, plus planning policies, has accelerated a boom in multi-family construction, much of it directed at high-end consumers. In New York andLondon, wealthy foreigners as well as the indigenous rich have invested heavily in high-rise apartments, many of which remain empty for much of the year. In San Francisco, for example, roughly half of all new condos are owned by non-residents, including both Chinese investors and Silicon Valley executives.

Since the vast majority of people cannot afford to buy these apartments, even if they want them, this kind of construction does little to address the country’s housing shortage. Much of the building in the most expensive markets, such asWashington, is well out of the reach of the vast majority of residents, which should be sending warning signals to investors.

The signs of an impending downturn are already there, for those who wish to look for them. In Southern California, which has seen the most multi-family construction in recent years, multi-family starts have dropped dramatically this year from last; a similar process seems to be occurring in the ultra-expensive San Francisco metropolitan area, where currently only 11 percent of homes can be afforded by the median income family. This is one-sixth the national rate. Washington, Philadelphia, Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston and Phoenix—once hotbeds of apartment construction—have also slowed appreciably.

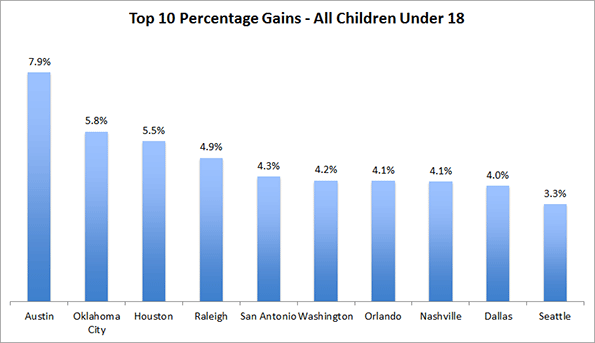

The high-density push by investors and regulators also misses the larger demographic trend. Suburban growth may have slowed in the immediate aftermath of the recession, but Trulia reported that between 2011 and 2012 less-dense-than-average ZIP codes grew at double the rate of more-dense-than-average ZIP codes in the 50 largest metropolitan areas. By 2013 urban core growth, then about as fast as suburbs, had once again slipped behind suburbs and exurbs. These trends intensified by 2014, with the biggest growth in exurban areas, repeating the patterns that existed before the crash.

Nor are the preferences likely to change—despite the predilections of pundits, planners, and the political class. As most millennials enter their 30s by 2018, economist Jed Kolko suggests that demand for suburban single family houses is likely to increase dramatically. Contrary to urban legend, most surveys reveal that millennials overwhelming prefer a home in the suburbs. Even the Urban Land Institute, historically no fan of the suburbs, found that more than 60 percent of the entire generation (PDF) expects to be living in a single family house by 2020, six times as many who plan to reside in a mid- or high-rise building.

The payback for ignoring the market could be imminent. In Boston, demand for space in expensive residential buildings—where a 500-square-foot studio in the Fenway Park area starts at $2,700 a month, and new two-bedrooms stretch into the $7,000s—may be headed toward a glut. Sound familiar?

Even some ascendant markets like Nashville, where apartment construction is growing more than 3 percent annually, appear to be on the way to being overbuilt. If there’s a downturn in tech, which seems likely in the next year or so, expect San Jose, Raleigh, and Austin to start seeing a decline in rents and greater competition for tenants. As we can see in China, Australia, Canada, and now at home, planners’ hubris about what is best seems to lead inevitably to a new real estate bust. What we don’t need is not so much more pack and stack housing, luxury units, and absentee owners but a return to an updated version of Levittown or Lakewood. This would help middle class families and would supercharge the economy, producing three times as many jobs as multifamily construction.

It’s about time for the political class to acknowledge that, in most cases, people know what they want better than those who claim to know best. That’s as true in Beijing or Shanghai as it is in Sydney, Toronto, or Los Angeles.

This piece first appeared at The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is also executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is also author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Wendell Cox is Chair, Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California) and principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm.He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: Shenzhen: Binhe Avenue from the Shun Hing Tower (by Wendell Cox)

![]()

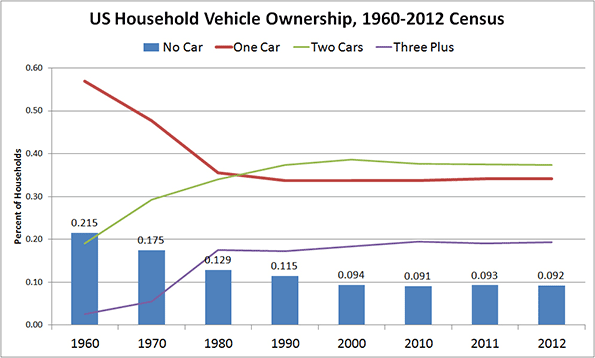

Chart 1 Source: Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Transportation Energy Data Book. Table 8.5.

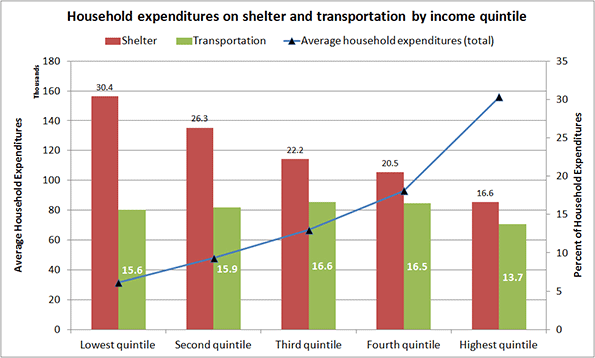

Chart 1 Source: Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Transportation Energy Data Book. Table 8.5. Chart 2 Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Household Spending. Table 2: Budget Shares Of Major Spending Categories By Income Quintile, 2012.

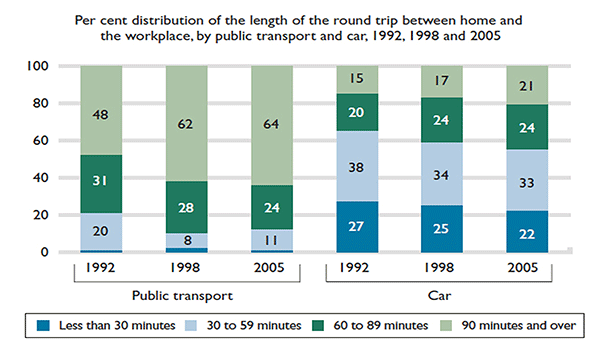

Chart 2 Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Household Spending. Table 2: Budget Shares Of Major Spending Categories By Income Quintile, 2012. Chart 3 Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, Trip Duration, 1992, 1998, and 2005.

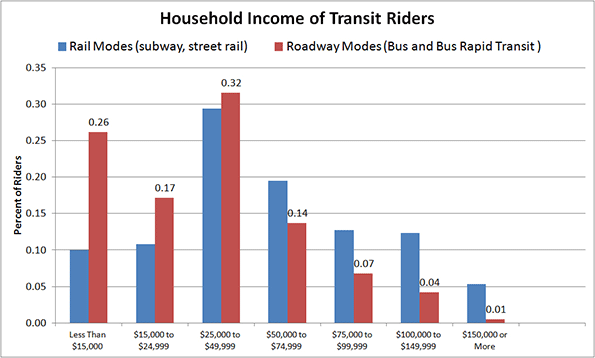

Chart 3 Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, Trip Duration, 1992, 1998, and 2005. Chart 4 Source: American Public Transportation Association, A Profile of Public Transportation Passenger Demographics and Travel Characteristics, 2007.

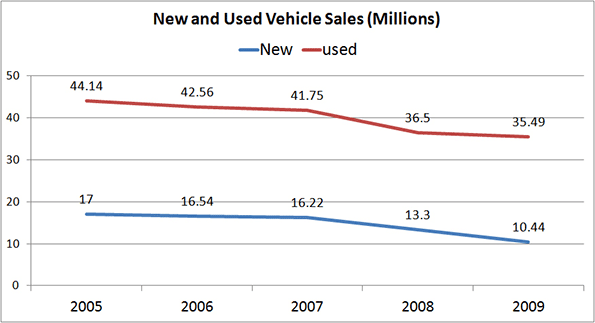

Chart 4 Source: American Public Transportation Association, A Profile of Public Transportation Passenger Demographics and Travel Characteristics, 2007. Chart 5 Source: NIADA’s Used Car Sales Industry Report; Relative Size of Car Markets for New and Used Cars, 2010.

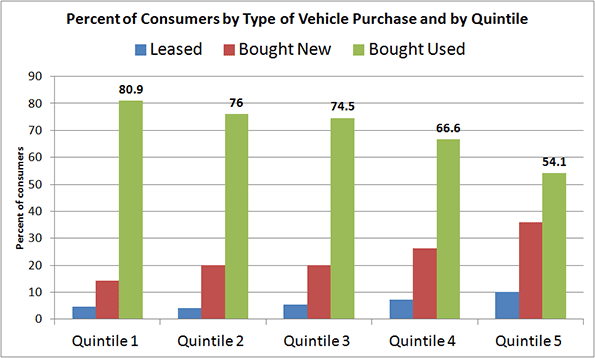

Chart 5 Source: NIADA’s Used Car Sales Industry Report; Relative Size of Car Markets for New and Used Cars, 2010. Chart 6 Source: Laura Paszkiewicz, The Cost and Demographics of Vehicle Acquisition, Consumer Expenditure Survey Anthology, 2003 (61) Division of Consumer Expenditure Surveys, US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Chart 6 Source: Laura Paszkiewicz, The Cost and Demographics of Vehicle Acquisition, Consumer Expenditure Survey Anthology, 2003 (61) Division of Consumer Expenditure Surveys, US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Chart 7 Source: The Used Vehicle Market in Canada, DesRosiers Automotive Consultants Inc., 2000.

Chart 7 Source: The Used Vehicle Market in Canada, DesRosiers Automotive Consultants Inc., 2000.