“So, about the slow growth/debt connection: I’ve done a quick and dirty mini-RR for the period 1950-2007 ……focusing only on the G7……and if you look at it, you see that most of the apparent relationship is coming from Italy and Japan……And it’s quite clear from the history that both Italy and (especially) Japan ran up high debts as a consequence of their growth slowdowns, not the other way around.” – Paul Krugman, Reinhart-Rogoff, Continued

Despite so much intense debate about the ailment from which Portugal suffers, and the mountain of sacrifices currently being borne by the Portuguese people one fact has gone virtually unnoticed in amongst all the noise - for the first time, at least in the modern era, Portugal’s working age population has started to shrink. Demography and its possible impact on economic growth is a topic which has been largely ignored by practitioners of economic science in recent decades as population growth has by-and-large been on an upward trend. However, as we enter a new period in human history, one in which the upward trend has shifted towards stagnation or even in some cases towards long run decline, the economic and financial implications of this transformation can no longer be ignored. As Nobel economist Paul Krugman indicates in the above quote, some countries have large debt simply because they have low growth.

So what is the common thread that runs through these low-growth high-debt countries? Could it be decelerating labour force growth and eventual labour force contraction? The cases of Italy and Japan are well known. In the case of Portugal, it will be argued here, demographic trends can not only explain a significant part of the slow economic growth the country experienced during the first decade of this century, they can also help us understand the depth of the current recession. More important still, we need to think about the consequences of this continuing lose-lose dynamic for the country’s future in both the short and much longer term.

Economists didn’t always take the view that population dynamics were irrelevant to economic performance. The 1930s gave birth to a serious debate about the possible problem that would arise if many decades of strong population growth were followed by population stagnation and then decline, a debate which was provoked by the fact that birthrates in a number of countries fell below replacement level for the first time in human history during the economic depression. And among the names of those economists who took the problem seriously enough to think and write about it was none other than John Maynard Keynes.

“There are, indeed, several important social consequences already predictable as a result of a rise in population being changed into a decline. But my object this evening is to deal, in particular, with one outstanding economic consequence of this impending change; if, that is to say, I can, for a moment, persuade you sufficiently to depart from the established conventions of your mind as to accept the idea that the future will differ from the past.” J.M. Keynes, Eugen Rev. 1937 April; 29(1): 13–17.

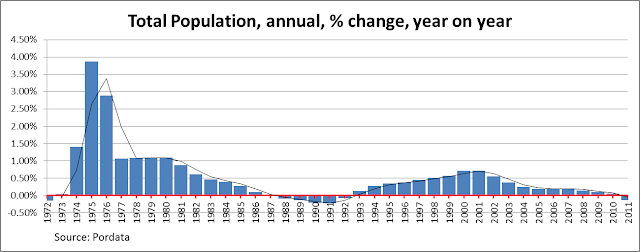

While the phenomenon has arrived largely unnoticed Portugal’s total population has long been near to stationary.

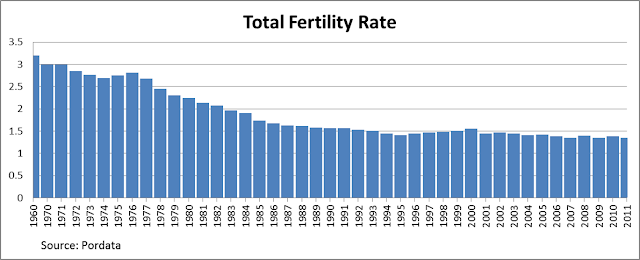

As can be seen in the above chart, Portugal’s population has been struggling to find growth momentum since the mid 1980’s (the first time numbers actually dipped downwards) but the years 2010/2011 seem to mark a more fundamental turning point, since it was in that time interval that Portugal’s population started on a long, and possibly irreversible, path of decline. Having long had a total fertility rate of below 1.5 this was a more than predictable outcome, and one that should have been expected ever since the total fertility rate fell (and stayed) below the 2.1 replacement level in 1982.

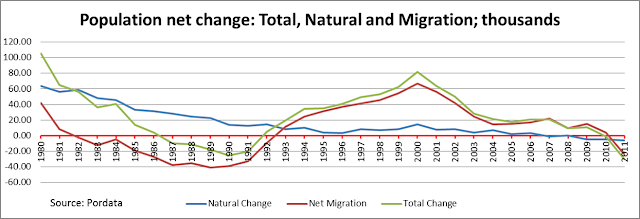

As is well known, population change is comprised of two major components: natural growth and net migration. Natural growth, births minus deaths, became negative in 2007 and thereafter population growth has become exclusively dependent on having sufficient positive net migration. Up to 2010 this condition was satisfied given the continuing influx of immigrants into the country as can be seen in the chart below.

However, since the onset of the 2008 recession, not only have the immigration flows reversed completely, but emigration has started to increase again, thus reanimating a trend that has been constantly present in Portuguese history over decades, even centuries. This is perhaps the most critical factor driving the recent population decline. In fact the decline would have occurred much earlier had it not been for the return of thousands of refugees from the Portuguese colonies in the 1974-1981 period.

According to the European Commission's 2012 Ageing Report, projections for the Portuguese population during the period 2010 - 2060 anticipated that population would peak in 2034, but as we have seen, the latest data show the population unexpectedly reached its peak in 2010 (total population, previous chart), the year in which the population began to decrease (a similar phenomenon seems to have occurred in Spain in 2012, with again a reversal in migrant flows in an otherwise stagnant population being the trigger). This fact that this turnaround comes as a surprise is clearly the result over optimistic assumptions on the net migration front since the numbers for natural growth are well known and change little (although birth numbers are now dropping in many EU countries under the impact of the long recession). Clearly the unexpected factor here is the severity of the recession from which the country is suffering and the size of the exodus of young people who are leaving.

Just to highlight even more the speed with which all this is happening, in Japan, the interval between the beginning of the decline of the working age population and the beginning of total population decline was a full decade. In Portugal this interval was only two years.

Even more relevant than the decline in total population for the purpose of the present discussion is the decline in the working-age population. While the former gives us a good proxy for domestic consumption, it is the later which is important in terms of potential national output. All other things being equal a reduction in the working-age population means a reduction in output. Therefore, the most important detail to catch from the chart above is that the working-age population, defined as the population with ages ranging from 15-64, declined for the first time in Portugal between 2008 and 2009. As highlighted by both Daniel Gros and Paul Krugman if you want to compare economic growth performance as between countries with growing populations and those with declining ones the best indicator to use is undoubtedly GDP per Working Age Person (GDP/WAP).

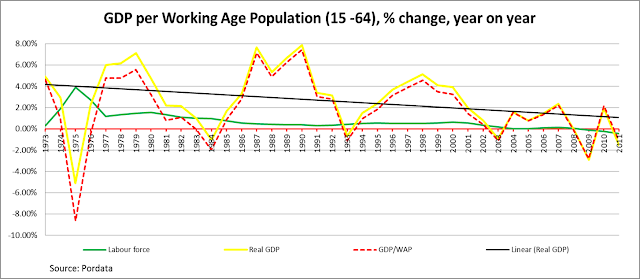

In the Portuguese case if we take this ratio and compare it with both Real GDP growth and Working Age Population change (my calculations VM), we can get an impression of how variations in the Working Age Population affect the economic growth of a country. Surprisingly or otherwise, the data for Portugal viewed graphically not only confirms the existence of the “workforce effect” – the relationship seen between Real GDP and GDP/WAP - but also suggests that Portugal has already passed the point where this effect is beginning to have a negative impact on GDP growth.

As can be seen in the above chart, until 2008 the growth rate of Real GDP was always higher than the rate for GDP/WAP offering a strong suggestion that labour force growth was having a positive impact on GDP growth. It is noteworthy, however, that both in the period 1986 - 1991 and in the period 2003 - 2008, the growth rates of Real GDP and GDP/WAP almost overlapped. This phenomenon coincided with very low or zero rates of working age population growth and as such the “workforce effect” was mostly neutral. The first of these periods, 1986 - 1991, the stagnation in the workforce was the direct result of the increase in emigration that followed the entry of Portugal in the European Union. The second one coincides with the arrival of the turning point in long term WAP growth, as the size of the working age population irrevocably turns negative.

Indeed, during this early period of emigration towards the EU Portugal’s total population decreased, as shown in the chart Population by age group (above, blue line), but at the time, since the population in general was much younger, and many more new labour force entrants were arriving at working age, the growth rate of the workforce remained slightly positive. In other words, there were still enough Portuguese entering the labour market to replace those who were leaving it (either to retire or to seek a future abroad). In the second period, 2003 - 2008, the large exit of Portuguese nationals, about 700,000 between 1998 and 2008 according to research by the now Economy and Employment Minister Álvaro Santos Pereira, was to some extent offset by an inflow of immigrants, but these were only sufficient in number to maintain the workforce at a stationary level.

All this calm and stability disappeared, however, after 2008 when the growth rate of Working Age Population turned negative, i.e. the labour force began to decline (see graph below). Where the growth rates of Real GDP and GDP/WAP overlap we can surmise that working age population change is having no effect on real GDP growth. Subsequently, however, the growth rate of GDP/WAP becomes higher than the growth rate of Real GDP and thus the "workforce effect” starts to act as a drag on the economy steadily bringing the potential overall growth rate down. In other words, Portugal is now suffering from a "Shortage of Japanese" as Edward Hugh has called the phenomenon, after Paul Krugman originally coined the term to describe the underlying problem which has been afflicting the Japanese economy since the mid-1990s.

The fact that the three lines in the above chart happen to intersect at zero is perhaps just an unfortunate coincidence but is consequences are disastrous, since the downward trend that was already evident accelerated greatly after the onset of the recession. The resulting rise in unemployment not only caused a collapse in the immigration flow, it also led to a sharp increase in emigration. As a result workforce shrinkage intensified even further, as can be seen in the above chart by looking at the growing distance between the Real GDP and the GDP/WAP lines. That is, if the workforce had remained stationary the economy would be growing at similar rates to the GDP/WAP, i.e. above the current level as indeed happened in the period 2003 – 2008.

Naturally, the argument can be advanced here that the recession is a cyclical phenomenon, and this is surely true, there is an ongoing cycle, but the argument being used refers to long term trends – a reversal in direction (or change of sign) for inputs from the labour force component brings down the overall trend growth rate making booms weaker and recessions deeper, all other things being equal. This would seem to be a simple conclusion which stems from elementary growth accounting theory. Naturally, there are other factors which contribute to growth, like multi factor productivity, but again other things being equal you would need more of this to achieve the same growth rate as before under conditions of weakening in the labour force growth component.

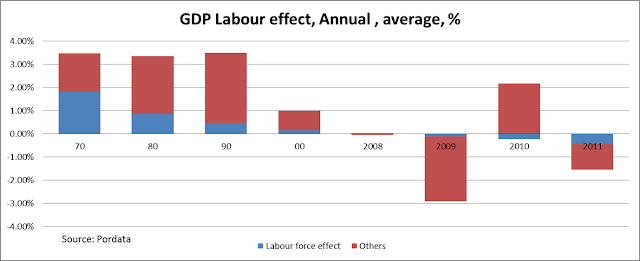

Thus the argument is not that economic growth becomes impossible with a stagnant or slowly declining workforce, but simply that it becomes harder to achieve because it relies more on other factors, such as productivity and raising participation rates, but these change slowly over time, and more so in already developed countries. As such trend growth will surely steadily fall. This can be clearly seen in the following chart: while workforce growth was an important source of growth when Portugal was a developing country, its importance fell back as the workforce started to stagnate even as Portugal was approaching converge with other developed countries in terms of productivity. Other factors took over and increased their importance steadily as the economy started to converge with more advanced ones. Now that this catch up process seems to have come to a standstill as well the economy simply can’t growth, at least at rates considered normal. With a stagnant workforce, low growth or no growth is the new normal.

Following standard growth accounting procedures, during the 1970s workforce growth accounted for more than half of Portuguese economic growth (see chart above, my calculations VM), and this contribution had fallen to only 16% in the first decade of this century. However, since 2008 not only has this contribution reversed sign but also the magnitude of the negative effect has begun to increase rapidly. Such that, by 2011 the “workforce effect” could be considered to explain more than 29% of the GDP decline. This “negative drag” will continue, and the effect possibly become greater, as the working age population shrinks further. Had the workforce remained stationary we could surmise the 2010 recovery would have been more pronounced and the 2011 recession wouldn’t have been so deep. This is the principal reason why official growth forecasts have been being constantly revised to the downside, and this will continue to happen until the models the forecasters use adequately incorporate the effects of population decline on economic growth. Adding insult to injury, ignorance of the existence of such effects recently led Portugal’s Prime Minister Pedro Passos Coelho to suggested young unemployed Portuguese resort to emigration as an escape route from the crisis, advice thousands have now followed thus making a bad situation even worse.

Economic growth in Portugal appears to be on a long downward trend, a trend which will only be made worse by the onset of the decline in its working age population. Economic output is now at 2001 levels and thus we can now conclude that the last decade has been completely lost. More worryingly though, is that after such a bad start to this decade, it might not be unreasonable to conclude that this one is also in the process of being lost too.

At best the economy will stagnate in the years to come but the possibility is there that it will continue to regress – especially if nothing is done to stem the outflow of young educated people - and by 2019 it might even be back somewhere in the 1990’s. This is scenario simply cannot be excluded since, in addition to all the other problems the country faces, a situation that would be in any circumstance challenging is now being aggravated by one more variable whose contribution cannot be easily reversed in the short term – the decrease in the working age population. More than the fact in itself, it is the speed at which this is happening which is alarming, and the fact that policymakers appear unaware of the problem. In analyzing the low Portuguese economic growth issue the decrease in the country’s working age population can no longer be ignored! Or at least it is hoped that this will be one of the outcomes of this short report.

To return to where we started, Keynes concluded in his pioneering presentation that a stationary or slowly declining population could increase its standard of life while preserving the institutions society values most if, and only if, the process was managed with the necessary strength and wisdom. On the contrary, he argued, a rapid decline in population, of the kind that we are seeing in Portugal today, would almost inevitably result in a serious decline in living standards and a breakdown in highly valued social security mechanisms. The distinction Keynes drew some 80 years ago between rapid and managed rates of decline seems plausible, reasonable and highly relevant today. What we now need to see are urgent measures taken – initiated by the EU and the IMF - to counter the exodus which lies behind this dramatic decline which is occurring before our eyes, measures which at least try to decrease its speed, because once a process like this gains full velocity it will be very difficult to stop, and we have already seen it gather considerable traction. Ireland is a pointer and a great example to learn from, since it took that country more than a century to recover the population decline precipitated by the Great Famine which hit the country in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Valter Martins is a self-taught economist and his research interests include demographics and its impact on economic growth. He holds a degree in International Business from University of Minho, Portugal and a Professional Diploma in Financial Advice (QFA) from Ireland.

a collection of historical travel essays. His new book,

a collection of historical travel essays. His new book,