Once giants walked this earth, and some of them were Democrats. In sharp contrast to the thin gruel that passes for leadership today, the old party of the people, with all its flaws, shaped much of the modern world, and usually for the better. Think of Franklin Roosevelt or Harry Truman, John Kennedy, or California’s Pat Brown, politicians who believed in American greatness, economic growth, and upward mobility.

For more than 40 years, the Democratic Party has drifted far from this tradition, its policies increasingly a blend of racial and gender politics combined with a fashionable brand of environmental fanaticism. No longer does it constitute a reliable, middle class-based alternative to the corporatist mindset of the Republicans. “Today’s Democrats have no more in common with Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson ,” notes author Michael Lind, “than today’s Republicans have in common with Abraham Lincoln or Dwight Eisenhower. “

To regain their relevancy, Democrats need to go back to their evolutionary roots. Their clear priorities: faster economic growth and promoting upward mobility for the middle and working classes. All other issues—racial, feminine, even environmental—need to fit around this central objective. In survey after survey, economic issues such as unemployment, the economy, and the federal budget top the list of concerns while affirmative action, gay rights, and climate change barely register.

From Obama Back to Jackson

Democrats do not need to become Republican lite, as was true among some New Democrats (I was a fellow with the Progressive Policy Institute, the New Democrats think tank). Democrats need to respond aggressively to the crony capitalism practiced by many Republicans, particularly regarding Wall Street. But they can’t do that if all they offer in its place are policies that service instead their own cronies not only in finance, but technology and media as well.

Right now it’s hard to make the case that the Democrats have a strategy to improve the economic prospects of the middle class. The New York Times’s Tom Edsall notes notes that after six years of Obama, voters stubbornly hold unto pessimistic views about the future. Of course, declining or stagnant wage growth started well before this president took office. Nevetheless, Democratic rule has not only failed to halt the trend, but appears to have accelerated it.

Not surprisingly, many middle and working class voters, particularly whites, have deserted the Democrats in increasing numbers. This November, notes Gallup, support for Obama among white college graduates dropped to 41 percent while his support among those without degrees fell to a pathetic 27 percent.

Critically, in 2014 this erosion began to extend to millennials; white millennials, particularly those without BAs (the vast majority), went Republican. This is a generation that, according to the Census, is both somewhat more educated than previous ones but far more likely to live in poverty.

Although likely to reject Republican views on social issues, such as gay marriage, millennials may not become “permanently blue,” as imagined by some boomer progressives. Faced with the consequences of slow, and poorly distributed growth, they are already less likely to see themselves as environmentalists than the national average and particularly the generally better off boomers.

Some progressives suggest that working class voters, particularly whites, can be lured back to the party by expanding the welfare state even further. But such an approach works against the traditional pride in self-sufficiency espoused by many in the American middle class. The old Jacksonians challenged financial power—then the Bank of the United States—but also worked to expand the economy, opening new lands to settlement, and encouraging home ownership and grassroots entrepreneurship.

The Key Issue: Energy and Climate Change

It would be difficult to find an issue with less resonance with the vast majority of voters than climate change. Concern over the environment has dropped since the Recession, notes Gallup, with climate change ranking near the bottom in voter concerns. In this sense, the emergence of Tom Steyer and other gentry yokes the party to a message with limited appeal once you get a few miles inland from either coast.

This does not reflect lack of interest in a better environment. Instead, it is a rejection of the Clerisy’s “solutions” to environmental challenges—such as banning suburbs, hiking electricity rates, and opposing new pipelines. These policies don’t hurt the super-rich; they hurt middle and working class voters. Lower oil prices, a product of fracking and other new drilling technologies, represents a boon to the dispersed, largely suburban electorate. But at the same time cheap gas offends progressive writers like the New Yorker’s Michael Specter, who argues that lower oil prices simply reinforces our addiction to an “industrial form of crack.”

In the next decade, the Obama administration’s bizarrely naïve “agreement” with China threatens to further weaken middle class interests. The South China Morning Post suggests westerners should be skeptical about prospects that China will sacrifice economic growth and, even more important, political stability in favor of planetary salvation. As one Canadian commentator put it, the Chinese deal constituted “a promise in a rented tuxedo” by a country that will cross “its coal fired heart” while the U.S. and the E.U. essentially disarm their economies with ever more draconian regulation.

Sadly, this choice between growth and climate change may not be necessary. The development of new drilling techniques has sparked a shift from coal fired power to natural gas that has allowed the U.S. to reduce its emissions faster than any major country, far more, indeed, than the self-righteous Europeans whose expensive and inefficient green policies have left them burning more coal.

Expanding, Not Constraining Geography

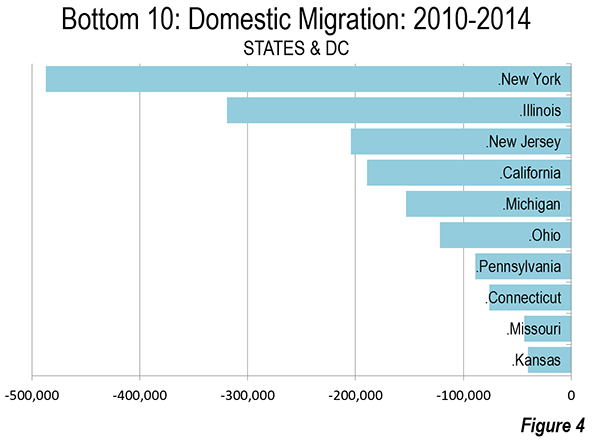

The rapid shrinking of the party’s geographic base is one clear legacy of the Obama years. Energy policy has been key here. Democratic losses have been heavy in those parts of the country that either produce fossil fuels, such as Louisiana, Texas, Colorado, Utah, and Montana, or those, notably in the upper Midwest, that depend on cheap fossil fuels to drive their still critical manufacturing sectors.

The losses of Democrats in states like Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin are arguably the most critical since these are traditionally swing states. The Steyer strategy of wiping out fossil fuels and raising energy costs might appeal to the denizens of climatically mild and highly affluent San Francisco. But people in a hardscrabble factory town in less temperate central Ohio or in greater Detroit , or even interior California, are less well-positioned to indulge green purity.

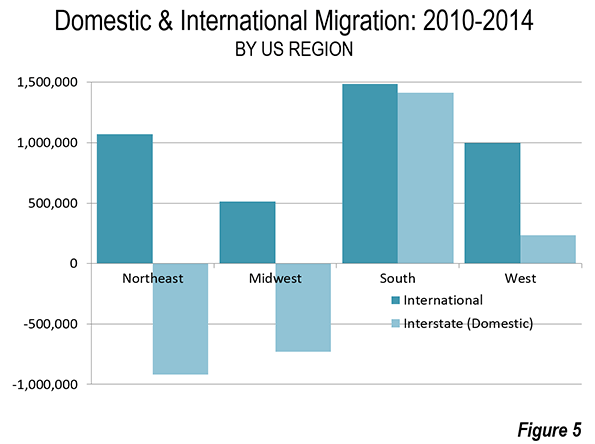

And how about the South? As recently as 2008, Democrats held one-third of the South’s Senate seats. Now it’s down to two, one in Virginia and the other in Florida. Convinced the region is lost permanently, some suggest suggest that Democrats “dump Dixie” so as not to have to appeal to voters in what one progressive writer denounced as a “fetid place.”

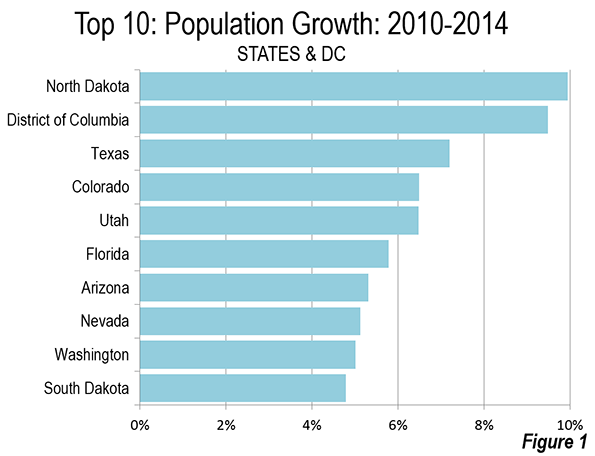

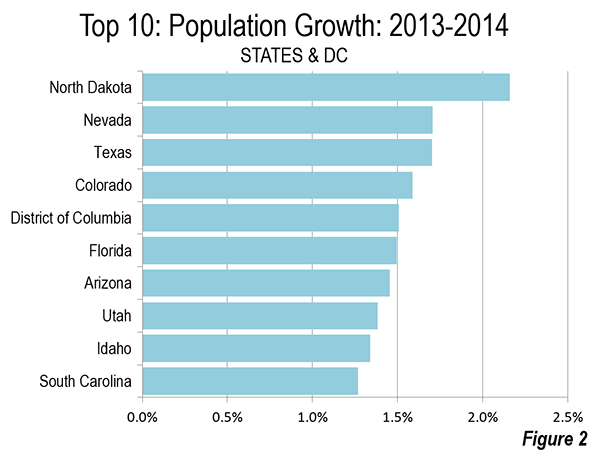

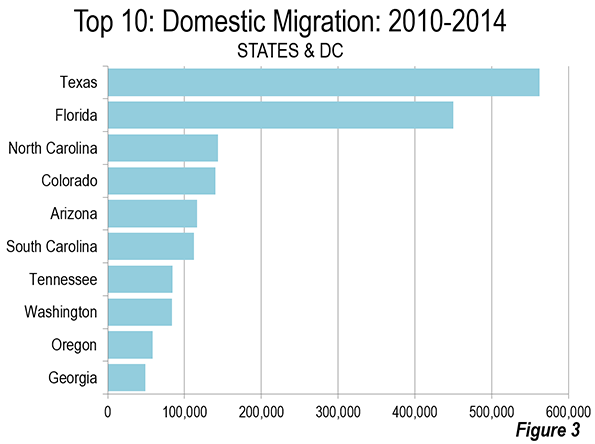

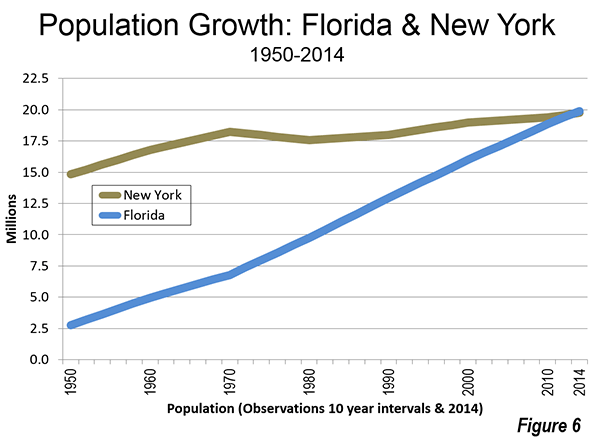

But the South accounts for almost 40 percent of the nation’s population, an impossibly large region to simply write off. But even progressives who want to take back the South, such as the New Republic’s Michael Cooper seek to build a coalition of poor whites and minorities in alliance with the growing numbers of graduate-educated professionals. This does not really address the aspirational reasons why so many Americans have been migrating to this region.

In many ways these attitudes reflect the increasingly urban-centric focus of the party. It diverges dramatically from the approach of traditional Democrats, from Roosevelt and Truman to Clinton, himself the former governor of a poor Southern state, who looked favorably on dispersing growth, particularly to the traditionally poor South, intermountain West and Great Plains, as well to the suburban interior.

Hostility to the non-urban regions includes a detestation of suburbia. Progressive theorists, like Salon’s Benjamin Ross, like to pin the detested “suburban sprawl” on Ronald Reagan, ignoring the basic fact that suburban growth was fostered for a half century by a Democratic controlled Congress, and was also favored by Democrats from Truman through Clinton. No surprise then that aside from wealthy coastal suburbs, the Democratic base has shrunk to the urban cores and college towns.

Infrastructure for Growth

Senator Charles Schumer’s retro perspective about the folly of enacting Obamacare in 2009 revealed much. Schumer rightly pointed out that Obamacare, for all the positives associated with expanding health care coverage, helped a relatively small part of the electorate, as well as the insurance companies.

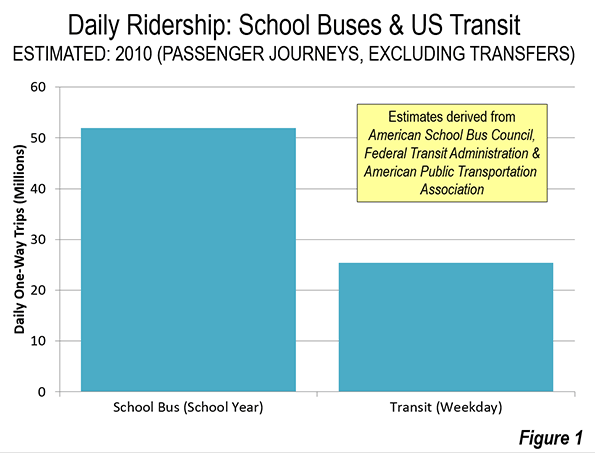

A far better move in the early years of Obama’s first term would have been to implement a updated version of the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration. A new WPA would have helped create jobs and provided some training to underemployed or unemployed youth. It could have left a legacy of improved roads, bridges, expanding port facilities, and affordable (usually bus) mass transit options that would appeal to many Americans.

In contrast to Obamacare, a neo-WPA would have been a difficult target for the GOP. It likely would have appealed to many business people on Main Street, few of whom are free-market fundamentalists. But moves to push such a program elicited opposition from critical parts of the party base, including feminists, who feared that public works would disproportionately help “burly men.”

Greens also were less than enthusiastic about new massive public works. Environmentalists today generally prefer to limit roads and block new water projects, even in parched California. So the Obama stimulus will be forever linked to insider deals with green energy epitomized by the Solyndra fiasco and massive loans to politically allied venture capitalists.

Class Not Race

The growing opposition towards Hillary Clinton’s ascension has one thing right: Democrats should not be seen as the second party of Wall Street. Obama’s recovery and Fed policy have, as Democrats like Elizabeth Warren like to point out, often favored the financial oligarchs, although their support for Democrats makes them far less keen on taking on the Silicon Valley Venture Capitalists, who have also profited under Obama. High valuations—even absurd ones—enrich the insiders who found companies, underwriters, and merger mavens, but those valuations have done precious little for the vast majority of Americans.

Faced with the loss of middle class voters, the administration seems determined to double down on its current coalition. So to whom do they turn to determine their future political direction? Not to a successful elected official from a swing district or a Main Street businessperson but to Google’s Eric Schmidt, an oligopolist of the first order from the party’s new heartland around the San Francisco Bay Area.

Given their cozy ties to Wall Street and oligarchs like Schmidt, the Democrats have failed to push class warfare as an issue, preferring instead to play the racial trump card. They allow issues to be dominated by such flawed emissaries as the detestable Al Sharpton, whose job seems to be the stoking of African-American ire. Similarly, the president’s executive order on undocumented residents follows this approach, by trying to appeal to Latino racial interests.

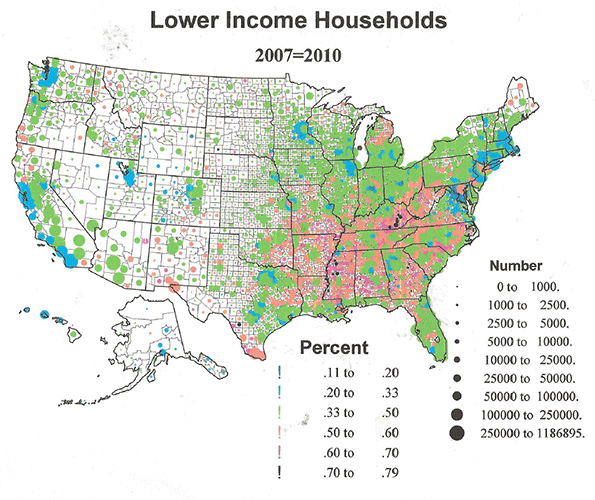

Yet race politics has limited appeal to whites, and ultimately may not guarantee keeping many minority voters in check. After all, minorities have fared poorly under Obama: a recent Pew study found minority incomes dropped 9 percent between 2010 and 2013, while only 1 percent among whites. Hispanics, notes a recent Pew survey economic issues easily trump immigration. Texas Republicans, for example, got close to half the vote among Latinos in that state, and similar results were found in Kansas. Even in places as blue-leaning as Colorado, Latino support for pro-growth Republicans has been growing. And Asians also showed a shift toward the GOP in the mid-terms.

Embrace Exceptionalism

Historically Democrats, like Republicans, believed in American Exceptionalism. This sometimes spills over into messianic overkill—for example, under Woodrow Wilson and George W. Bush—but overall the ideal of a uniquely American national profile has been embraced by Democrats from Jefferson and Jackson to Roosevelt, Truman and, arguably the last of the breed, Bill Clinton.

President Obama, in contrast, has openly rejected this notion, perhaps reflecting the world view of academics and much of the financial world that sees American Exceptionalism as some sort of patriotic nonsense. In the past the old Democrats saw the country’s broad resources and continental scale as primary sources of national greatness. Early conservationists did not oppose the expansion of industry, mining, or growth as inimical to progressive ideals; instead, they sought to restrain the abuses of the capitalist classes in order to prevent gouging as well as to preserve resources and open space for future generations.

In sharp contrast to their modern “heirs,” both Progressives and New Dealers were builders of dams, roads, and electrical power systems. They embraced the notion of a growing America, whose economy could be expanded for the benefit of the majority.

Is There a Messenger For Dino-Democrats?

Hillary of the many houses, $200,000 speaking gigs, Wall Street linkages, and her aging, wealthy glitterati backers does not exactly appear the ideal messenger for a neo-Jacksonian revival. Rather than the “shot and a beer” Hillary who came back to almost save her 2008 effort, she now reflects gentry views on both economics and climate change in ways that do not significantly diverge from President Obama.

With dissatisfaction with the economic status quo strong among many traditional Democrats, it’s likely populist candidates could emerge. Some imagine Senator Elizabeth Warren as the charismatic leader of a progressive version of the “tea party.” She has been a strong and vocal critic of Wall Street, which is to her credit, but her base lies not in middle class voters but among academia and wealthy Boston suburbs. On environmental issues, she seeks to out-green Hillary, something that might not appeal to voters in Ohio, Indiana, and a host of other key states.

Bernie Sanders, the self-described socialist, represents an emotionally appealing alternative to the endlessly grifting Clintons and the law professor Warren. But Sanders, a representative of the Northeastern vacation state of Vermont, also opposes fossil fuel development. This approach would greatly limit his appeal beyond the Northeast and the west coast. It’s hard to envision him campaigning for votes at Great Lakes factories that depend on coal power, or appealing to construction workers who would love to see the Keystone and other pipelines built.

Right now, former Virginia Senator James Webb may prove the best vehicle for dino-Democratic ideas. A self-conscious inheritor of the Jacksonian tradition, Webb epitomizes the individualist and populist values of his Scotch-Irish forebears. With a strong military background, he also appeals to nationalists who inhabit the South, Appalachia, and the non-coastal parts of the West. Whether his candidacy takes off is still an open question, but the ideas and spirit he embodies could revive a Democratic tradition that, although now submerged, might provide the party with a way out of its current morass.

This piece first appeared at The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

![]()

a collection of historical travel essays, and

a collection of historical travel essays, and