“There is a secret at the core of our nation. And those who dare expose it must be condemned, must be shamed, must be driven from polite society. But the truth stalks us like bad credit.” – Writer Ta-Nehisi Coates

***

With the recent Supreme Courts strike down of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which was created to protect minority representation, the headline in the Huffington Post read “Back to 1964?” While some contend the title hyperbolic, the HuffPost lead, if not the strike down itself, reflects the reality of a country still tethered to its discriminatory past.

This reality is reflected in all facets of American society, including urbanism. Specifically, is the “back-to-the-city” movement destined to become 1968 inverted; that is, instead of “white flight” there’s “white infill”? If so, the so-called “game-changing” societal movement will be a process of switching out the window dressing, with the style du jour less lace curtains, more exposed brick.

While debatable, there appears to be a back-to-the-city trend, particularly the inner-core areas of America’s largest and most powerful cities. For instance, according to a recent report by the Census Bureau, Chicago’s core exhibited a 36% boom in its population from 2000 to 2010—a gain of nearly 50,000. Rounding out the top five core-growth gainers were the cities New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Washington D.C. The report finds that, on average, “[T]he largest metro areas—those with 5.0 million or more population—experienced double-digit percentage growth within 2 miles of their largest city’s city hall…”

Who is moving into these “spiky” urban cores?

Whites largely. For example, much of Chicago’s core gains comes from the downtown zip code 60654, in which 11,499 (77%) of the area’s 14,868 incoming residents were white, and where the median family income is $151,000. Other zip codes in Chicago’s core share similar proportions of growth, such as 60605, with 70% of its 12,423 new residents being white. Contrast this with a 5% growth rate for blacks.

As well, according to research by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute examining the zip codes with the largest growth in the share of white population from 2000 to 2010, 15 of the top 50 were located in Philadelphia, New York, and Washington D.C. Philadelphia’s downtown zip code 19123 grew its population by nearly 40%, and its proportion of whites increased from 25% to almost 50%. In D.C., the growing core zip code of 20001 increased its white share from 6% to 33% in a mere 10 years. While in Brooklyn, the zip codes 11205 and 11206 showed similar growth dynamics, with overall gains of 15% and 18% respectively, and corresponding increases in the white share of approximately 30%. Also on the Institute’s list are zip codes in not-quite-global cities such as Chattanooga, Austin, Atlanta, St. Paul, Indianapolis, Tampa, and Portland, with the vast majority of the “whitening” areas located in, or besides, the downtown core.

Now, why does it matter if whites are leading the charge into those cores frequently championed as evidence of a new social order? After all, it is a step forward, right? Or, as urbanist Kaid Benfield recently wrote:

Inner cities are growing again. People of means, especially young people, want to be in cities today. While that carries its own set of challenges, I would submit that addressing the challenges of gentrification is a far better problem to have than coping with massive abandonment and rampant crime.

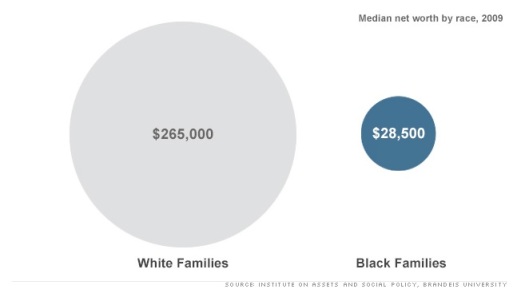

While that line of argument has merit, what’s missing is a deeper examination about those “people of means”. Specifically, a recent study out of Brandeis University showed the wealth gap between blacks and whites has nearly tripled over the past 25 years. That said, the people of means wanting to be in cities is largely the same people who always had means, and they are simply taking their means from one geography to the next; that is, from the suburban development to the urban enclave.

Of course many argue that infusing affluence into an area will create broad spillover effects. Tweeted urban planner Jeff Speck:

“A beautiful and vibrant downtown can be the rising tide that lifts all ships. #walkablecity”.

Yet there is little evidence of a “trickle down” effect within “rejuvenated” space. For instance, in his piece examining the aforementioned D.C. zip code of 20001, Dax-Devlon Ross writes:

In 2011 alone, condos accounted for 57 percent of total home sales (276), most at triple the 2000 median price. The zip code now boasts an Ann Taylor, a Brooks Brothers, an Urban Outfitters, enough bars to serve several university populations at once and a mind-boggling 10 Starbucks…

…What’s telling about the zip code’s “new build” makeover is that it did not move the poverty needle. The zip code’s poverty rate is exactly what it was in 1980, 1990 and 2000 — 28 percent — and the child poverty rate is nearly twice what it was in 1990 (45 percent).

In other words, such developmental strategy is a game of whack-a-mole in which the raison d’être for the mole won’t stop until real economic restructuring happens, or until equity truly starts entering into the lexicon of our shared language. Instead, we get the apologia of the status quo that is shifting the same affluence to the same pockets, switch out the spatial aesthetics of the parking lot for the parklet.

Trump Towers Chicago. Courtesy of Northwestern Univ.

That said, there is real doubt the country has the stomach for such discourse, let alone for policy that can affect the prioritization of human and community capital. From the article“Separate, Unequal, and Ignored”, the author suggests that “[r]acial segregation remains Chicago’s most fundamental problem”, and he questions why the issue remained muted during the recent mayor’s race. Answered Princeton sociologist Douglas Massey:

“[Segregation] is a very difficult and intractable problem. Politicians don’t like to face up to difficult and intractable problems, whatever their nature”.

Unfortunately for city proponents, this same inability to face the issue by leading urban thinkers is making the “new urbanism” movement look really old. Asked about the risk of racial and economic homogeneity at the hands of the “back-to-the-city” movement, Alan Ehrenhalt, author of “The Great Inversion and the Future of the American City”, answered this way:

I think you’re going to have class segregation no matter what you do. It would be nice to have people of all classes living right next to each other in gentrified downtowns. That’s probably not going to happen. It is true that a gentrified area tends to become less diverse. Cities can’t solve all problems.

No, cities can’t solve all problems. But neither should cities be used to make existing problems worse. Re-urbanism, or specifically the opportunities it creates for equitable reinvestment, should be respected for what it is: a chance to move forward from a divided, destructive past.

Yet such will take collective will and reflective honesty. Or the ability to look deep in the mirror at the American face and know that behind us is a persistence of failed history.

Richey Piiparinen is a writer and policy researcher based in Cleveland. He is co-editor of Rust Belt Chic: The Cleveland Anthology. Read more from him at his blog and at Rust Belt Chic.

Lead photo courtesy of Columbus Underground.

a collection of historical travel essays. His next book is Whistle-Stopping America.

a collection of historical travel essays. His next book is Whistle-Stopping America.