The newly released Census reports reveal that California faces a profound gap between the cities where people are moving to and the cities that hold all the political power. It is a tale that divides the state between its coastal metropolitan regions that dominate the state’s politics — particularly the San Francisco Bay Area, but also Los Angeles — and its still-growing, largely powerless interior regions.

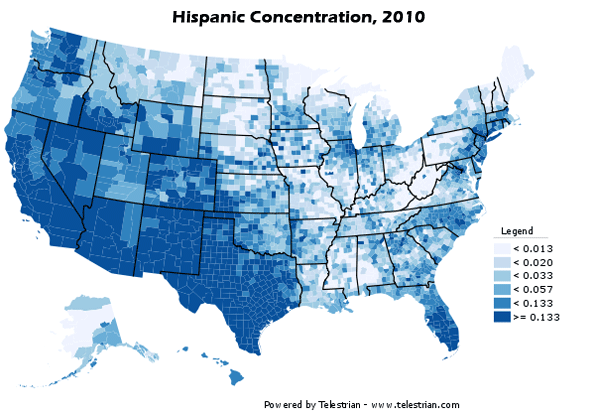

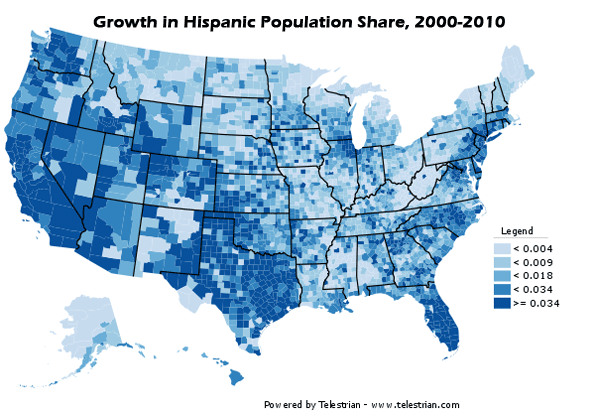

Indeed, the “progressives” of the coast are fundamentally anti-growth, less concerned with promoting broad-based economic growth — despite 12.5% statewide unemployment — than in preserving the privileges of their sponsors among public sector unions and generally affluent environmentalists. This could breed a big conflict between the coastal idealists and the working class and increasingly Latino residents in the more hardscrabble interior, whose economic realities are largely ignored by the state’s government.

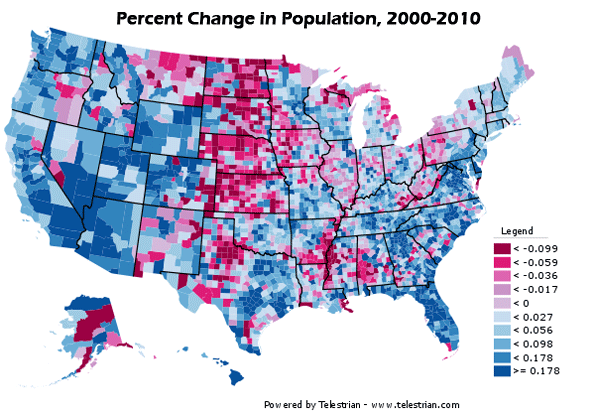

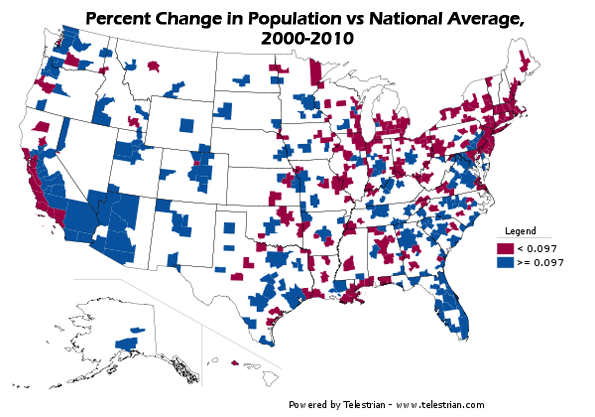

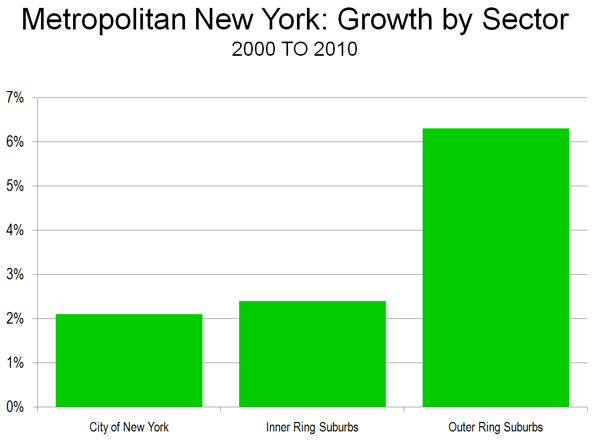

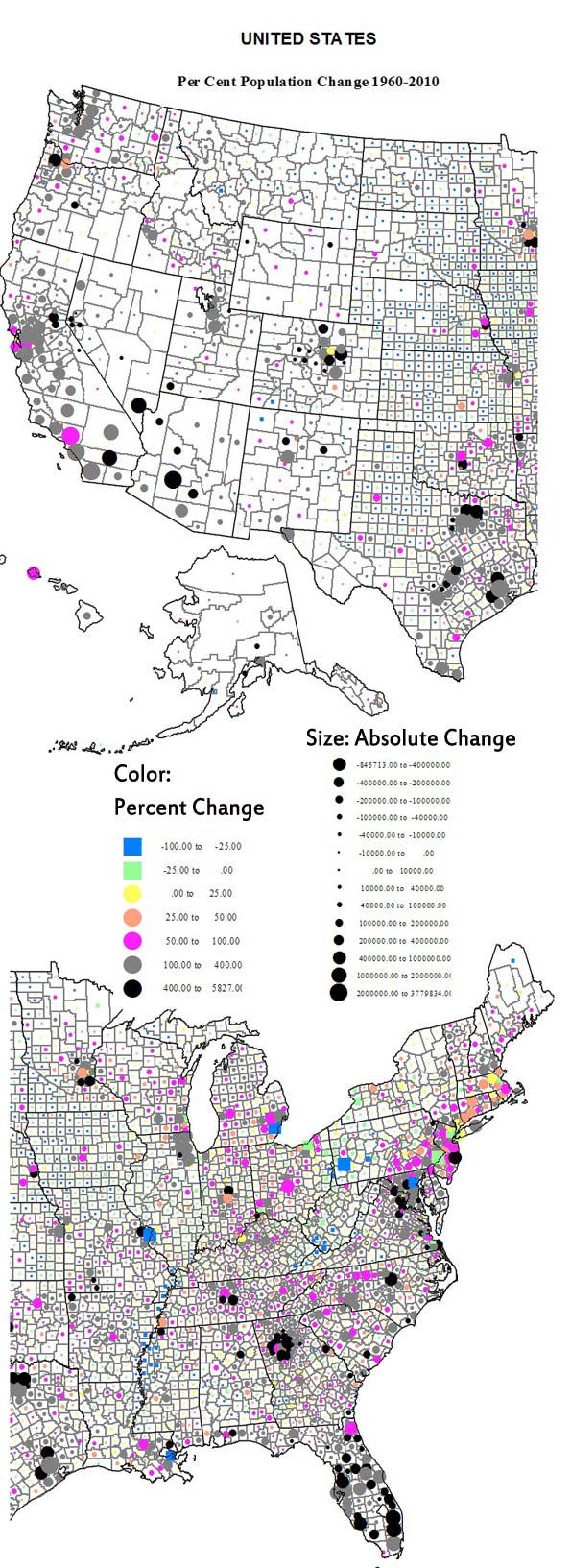

The Census shows that the Bay Area and Los Angeles are growing at their slowest rate in over 160 years under American rule. Between 2000 and 2010 Los Angeles gained less population than in any decade since the 1890s. Its growth rate was slower than metropolitan Chicago, St. Louis and virtually every region that has reported to date, with the exception of New Orleans.

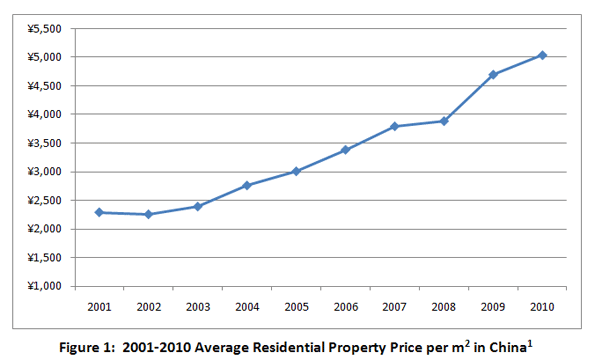

This reflects not only the poor economy of the past few years, but also a widely cited drop-off in foreign immigration and continued massive outmigration of residents to other states. One reason for this mass exodus may be soaring house prices — largely the product of strong regulatory restraints — which appear to have contributed to slowing population growth after 2003.

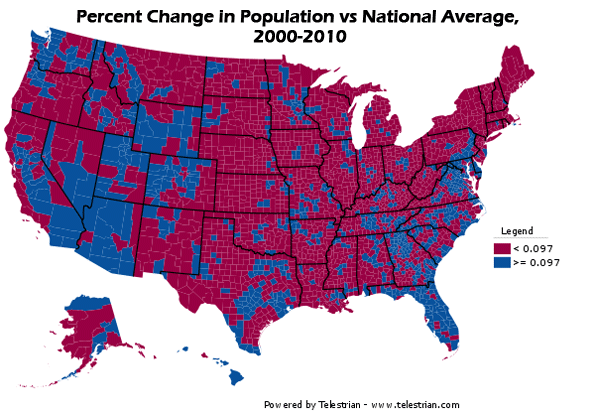

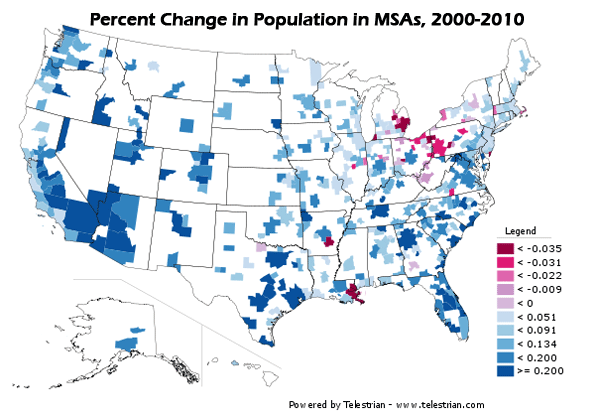

Yet not all of California is stagnating demographically. The state’s interior region — what I call “The Third California” — is growing steadily. While Orange County, Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose and the Silicon Valley increased their population by only 6% or less over the last decade, inland areas such as Riverside-San Bernardino, Sacramento and the Central Valley saw growth of 20% or more. Overall, the interior counties together gained 2 million residents , roughly twice as many as the combined coastal metropolitan areas.

The reasons for this growth are not difficult to comprehend. In boom times and hard times, housing prices in the coastal regions tend to equal as much as seven or eight times a median family income. The prices in the interior can be three times or less.

In addition, during the past two decades, the interior region enjoyed fairly strong economic growth. Pro-business county governments promoted the expansion not only of housing, which boosted construction, but of basic industries such as food processing, manufacturing and warehousing. According to economist John Husing, the Inland Empire alone accounted for over 40% of the state’s total job growth.

Today, in the wake of the collapsed housing bubble, these interior counties are reeling, with double-digit unemployment (in some cases reaching closer to 20%) and what appear to be diminishing prospects. Five of the nation’s 10 metro areas for foreclosures are located in California’s interior.

Under normal circumstances, lower housing prices and business costs would lead — as in past recessions — to a spate of new economic growth, but this the radical turn in California government could keep these areas permanently poor.

Essentially, the Third California has become hostage to the coastal cities and their increasingly bizarre economic policies. Under first Arnold Schwarzenegger and now Jerry Brown, California has embraced a series of radical environmental edicts that spell disaster for the more blue-collar interior. These include dodgy land use policies designed to combat “climate change” but essentially seek to steer middle- and working-class Californians out of their cherished suburban homes and into densely packed urban apartment complexes.

The last election confirmed the Bay Area’s ascendency in Sacramento. Gov. Jerry Brown was previously mayor of Oakland (a city that actually lost population this decade), while the lieutenant governor, former San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom, and the new attorney general, Kamala Harris, are from the city by the Bay. The San Francisco area’s population may be about the same as the Inland Empire’s, but its political perspective now dominates the state.

Husing describes San Francisco as “a bastion of elitist thinking” due to a large “trustifarian” class who have turned the city into favorite spot for green and fashionably “progressive” think tanks. This thinking is increasingly influential as well in a rapidly changing Silicon Valley. In the past the Valley was a manufacturing powerhouse and had to worry about such things as energy prices, water availability and regulatory relief. But the increasingly dominant information companies such as Apple, Facebook, Twitter, Google and their wannabes are widely unconnected to industrial production in the region. To be sure, they have created a financial bubble in the area that has made some fantastically rich, but according to researcher Tamara Carleton they have contributed very little in new net job creation, particularly for blue-collar or middle-class workers.

There’s a bit of a snob factor here. Fashionable urbanistas extol San Francisco as a role model for the nation. The City, as they call it, has adopted the lead on everything from getting rid of plastic bags and Happy Meals is now considering a ban on circumcision. When it comes to everything from gay rights to bike lanes, no place is more consciously “progressive” than San Francisco. So why should that charmed city care about what happens to farmworkers or construction laborers in not-so-pretty Fresno?

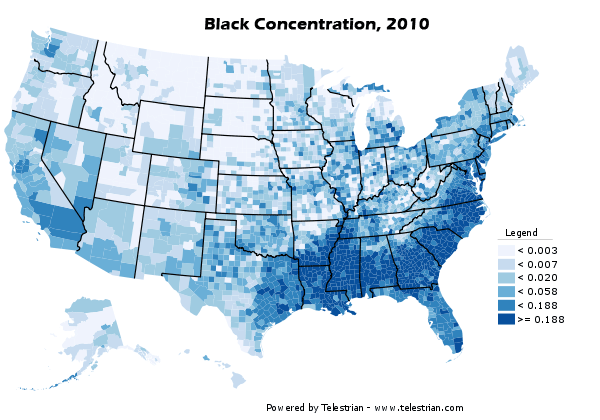

Class and occupational profile also has much to do with this gap between the Californias. Husing notes that the Bay Area has far more people with college degrees (42%) than either Southern California (30%) or the Central Valley (where the percentage is even lower). Green policies that impact blue-collar workers — restraining the growth of the LA port complex, restricting new single-family home construction or cutting off water supplies to farmers — mean little distress for the heavily white, aging and affluent Bay Area ruling circles.

But such moves could have a devastating impact on the increasingly Latino, younger and less well-educated populace of the interior. Outside of the oft-promised green jobs — which Husing calls “more propaganda than economics” — it is these less privileged residents’ employment that is most likely to be exported to other states and countries, places where broad-based economic growth is still considered a worthy thing. “By our ferocious concentration on the environment, we have created a huge issue of social justice,” Husing points out. “We are telling blue collar workers we don’t want you to have a job.”

This all presages what could be the greatest issue facing California — and much of the country — in the decades to come. In places where San Francisco-like fantasy politics preside, expect to witness a growing class and ethnic divide, with consequences that could prove catastrophic to the future of our increasingly diverse society.

This piece originally appeared at Forbes.com

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and an adjunct fellow of the Legatum Institute in London. He is author of The City: A Global History

Photo by wstera2

(Third Avenue Books), available only from Amazon.com and from Barnes & Noble. He is co-founder of

(Third Avenue Books), available only from Amazon.com and from Barnes & Noble. He is co-founder of

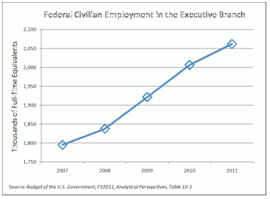

The second leg of Obama’s troika was new government employment. He was successful in signing his health care reform into law but delayed implementation to 2014. The 2010 election that changed 63 House seats to the Republicans, has acted to unwind much of this legislation. If not repealed outright, Obamacare will likely face starvation from Republican cuts in funding necessary to implement the 2,900 page law with its hundreds of new federal regulations. Federal civilian employment in the president’s 2012 budget, will be 15 percent higher in 2011 than it was in 2007. This effort is also likely to be stymied.

The second leg of Obama’s troika was new government employment. He was successful in signing his health care reform into law but delayed implementation to 2014. The 2010 election that changed 63 House seats to the Republicans, has acted to unwind much of this legislation. If not repealed outright, Obamacare will likely face starvation from Republican cuts in funding necessary to implement the 2,900 page law with its hundreds of new federal regulations. Federal civilian employment in the president’s 2012 budget, will be 15 percent higher in 2011 than it was in 2007. This effort is also likely to be stymied.