On July 31, voters in a 10 counties of the 28 county Atlanta metropolitan area will vote on whether to raise the sales tax by one cent for $8 billion in transit and highway projects over 10 years. The measure is highly tilted towards transit spending. Sadly, this would do virtually nothing to reduce Atlanta's traffic or its travel times.

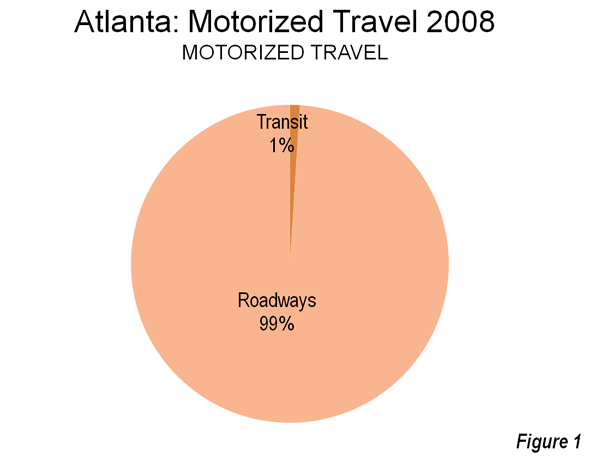

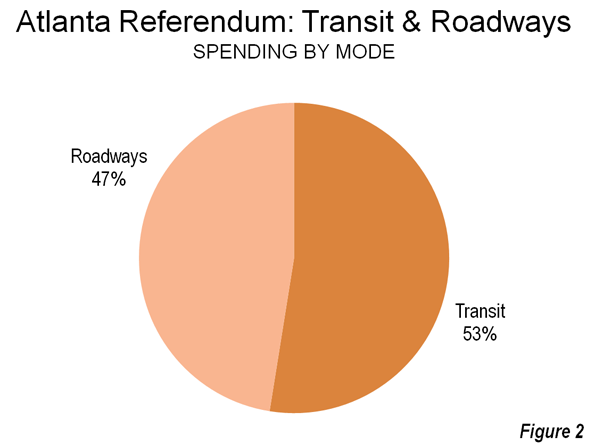

In a metropolitan area in which barely one percent of travel (Figure 1) and less than five percent of work trip travel is by transit, the tax measure devotes more than 50 percent of the funding to transit (Figure 2). Yet in reality, the focus of any transportation revenue issue should be on reducing travel times, whether by transit or highways. This is how transportation improves an urban economy. The reality is that with nearly all travel by highways and transit's inherently slower travel times, much of the tax money would have virtually no impact on reducing travel times or traffic congestion.

Atlanta's Traffic Congestion: Promoters of the tax claim that the highway projects will reduce traffic congestion. Atlanta is well known for its serious traffic congestion. There are two reasons for this:

- Atlanta’s sparse freeway system is limited to little more than a belt route (I-275) and three radial freeways (I-20, I-75 and I-85) that converge into two in the one place more capacity is needed, the core. Trucks are not permitted on freeways inside the beltway, which concentrates the considerable interstate traffic on a single roadway, I-275. If Atlanta had the higher freeway density (freeway mileage per square mile) of Los Angeles or Minneapolis-St. Paul, traffic congestion would be far less of a problem.

- Atlanta's regional arterial (high capacity streets) system is virtually non-existent. For this reason, I proposed (in 2000) development of a one-mile terrain constrained grid of arterials. The Atlanta Regional Council (ARC), the local metropolitan planning organization, has included a somewhat more modest (but useful) arterial grid in is regional plan.

Yet despite its reputation, Atlanta's traffic congestion could be worse. The latest INRIX National Scorecard rates the Atlanta metropolitan area as having the 15th worst traffic congestion in the nation, behind Portland, which is nearly 60 percent smaller and twice as dense, with its compact city policies. Among high-income world metropolitan areas with more than 5 million population, only Nagoya outside the United States may have a shorter work trip travel time (Note 1). Atlanta's world-competitive work trip travel time of 29 minutes is faster than that of far more transit-dependent Toronto (33 minutes), smaller Sydney (34 minutes) and much smaller Vancouver (31 minutes), despite their compact city policies.

The Transit Projects: So Much for So Little: The proposed transit projects have virtually no potential to reduce work trip travel times and traffic congestion. Approximately one-fifth of the transit funding would be used to rehabilitate and upgrade the MARTA subway system, a need that should have been legitimately funded from the existing MARTA sales tax. Another nearly 20 percent of the transit funding would be spent on the "Belt-Line" streetcar project in central Atlanta. The role of the Belt-Line is more "city building" (read "real estate speculation") than it is transportation. It will do nothing to reduce work trip travel times. Further, it is exceedingly costly. The extravagance of this project is illustrated by an annualized capital cost alone (principally construction) high enough to pay the lease on a new mid-sized car for each new regular passenger (Note 2). Moreover, that is before the likely capital cost escalation and the substantial operating subsidies (Note 3).

Transit's problem in Atlanta (and elsewhere) lies outside its core downtown job market (Note 4). Most destinations in a metropolitan area cannot be reached by transit in a way remotely competitive with the car. The transit tax would only modestly increase transit ridership. ARC projects the transit projects will boost daily transit ridership less than 10 percent. If all of the forecast new passengers were to be taken from cars (which is not likely), the net reduction in traffic volumes over ten years would be equal to less than three months of traffic growth. Put another way, at the best, the transit proposals would mean that the traffic congestion expected on January 1, 2025 would not occur until March of 2025. That's less than 90 days of traffic relief for 10 years of taxation.

The Road Projects: In a metropolitan area in which personal mobility predominates, roadway improvements, such as expansions, an arterial grid in Atlanta's case and completion of the GA-DOT HOT (high occupancy toll) system provide far greater potential for reducing travel times. There is another significant benefit to highway investments. As traffic speeds increase fuel efficiency improves and both air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions are reduced.

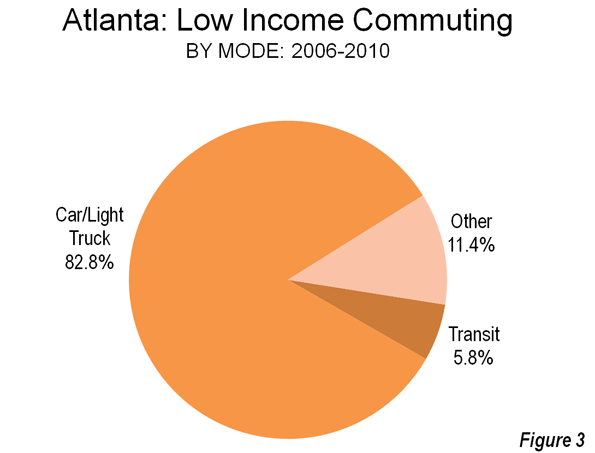

Under the tax referendum, a significant opportunity to improve mobility would be missed, to the detriment of the vast majority of Atlantans; over 88 percent of all commuters in Atlanta travel by car, but the figure is only slightly less (83 percent) among low income commuters (Figure 3).

What's Right About Atlanta: For all its problems, Atlanta has much to be proud of. Former World Bank principal planner Alain Bertaud said of Atlanta in a 2002 study:

While income and population were rising very fast, Atlanta managed to keep a very low cost of living. A worldwide cost of living survey conducted by the Economist Intelligence Unit in 2002 found that Atlanta had the lowest cost of living among major US cities and ranked 63rd among major cities around the world. This achievement is remarkable in view of the rapid rate of growth of the metropolitan area over the last 20 years. It shows that while demographic and economic growth has certainly contributed to generate pollution and congestion, the various actors responsible for the management of metropolitan Atlanta must have done a lot of things right. High income growth and high demographic growth combined with a low cost of living suggests that labor markets are functioning well and that housing does not encounter important supply bottlenecks (Note 5).

As successful as local land use policies have been in making Atlanta livable by making it affordable (the first principle of livability is affordability), local leaders need to start over with a proposal primarily designed to reduce traffic congestion, reduce travel times and grow the economy.

Politics Trumps Reducing Traffic Congestion: Traffic congestion is most effectively addressed by projects that reduce work trip travel times, since it is the concentration of work trips at peak hours that causes the worst congestion. The long-suffering commuters of Atlanta would have been far better served by a program that selected projects based upon their effectiveness in reducing travel times. A simple cost per hour of delay measure would have been appropriate. Atlanta deserves a much better deal.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

-----------------

Note 1: Based upon 109 metropolitan areas for which data is available. Japanese data is reported as median work trip travel time. Nagoya's median work trip travel time (27 minutes) is less than Atlanta's (29 minutes). The excessively long rail commute times of many Japanese commuters could make Nagoya's average work trip travel time as great or greater than Atlanta's. Dallas-Fort Worth has the shortest work trip travel time of any metropolitan area over 5 million population (and the lowest transit work trip market share)

Note 2: A team led by Oxford University professor Bengt Flyvbjerg found that passenger rail systems typically have cost overruns of 45 percent. If the average increase is experienced, the Belt-Line cost could escalate to $1 billion.

Note 3: The capital cost is discounted at 4 percent over 35 years, which equals more than $5,500 annually. A new Ford Fusion, Toyota Camry, Honda Accord or Nissan Altima could be leased for less than $5,000 annually, with no down payment, according to internet sources (such as http://www.leasecompare.com/)

Note 4: More than 93 percent of metropolitan Atlanta's employment is outside downtown (and Mid-Town). Downtown's share of employment declined from 2000 to 2009 (latest data available from the US Census Bureau, County Business Patterns).

Note 5: Atlanta was most affordable major metropolitan area in the US, UK, Canada, Australia, Ireland, New Zealand and Hong Kong in the 8th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey.

------

Photo: Atlanta Freeway (by author)