With two football teams moving to Los Angeles, a host of towers rising in a resurgent downtown and an upcoming IPO for L.A.'s signature start-up, Snapchat parent Snap Inc., one can make a credible case that the city that defined growth for a half century is back. According to Mayor Eric Garcetti, the Rams, Chargers and the new mega-stadium that will house them in neighboring Inglewood, show that “that this is a town that nobody can afford to pass up.”

And to be sure, Los Angeles has become a more compelling place for advocates of dense urbanism. Media accounts praise the city’s vibrant art scene, its increasingly definitive food scene and urbanist sub-culture. Some analysts credit millennials for boosting the population of the region and reviving the city’s appeal. Long disdained by eastern sophisticates, there’s an invasion from places like New York. GQ magazine called downtown L.A. “America’s next great city” last year.

Downtown has transformed itself into something of an entertainment district, with museums, art galleries, restaurants, and sports and concert venues. Yet it has not become, like San Francisco or New York, a business center of note. In fact, jobs in the region have continued to move out to the periphery; downtown accounts for less than 5% of the region’s employment, one-third to half the share common in older large cities.

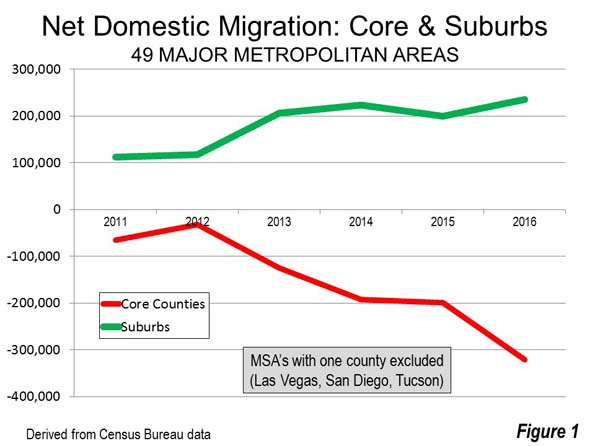

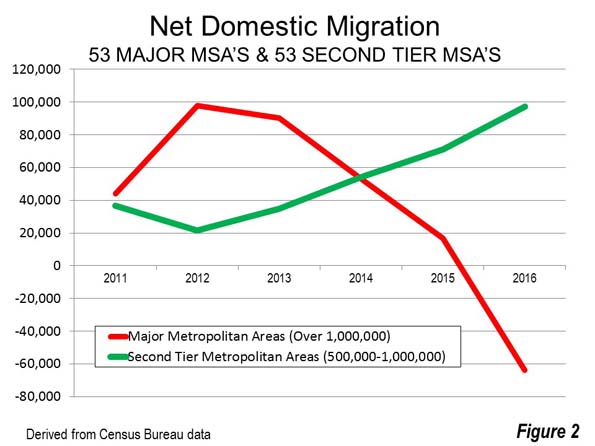

Downtown’s residential growth needs to be placed in perspective. Since 2000 the population of the central core has increased by only 9,500; add the entire inner ring and the population is up a mere 23,000. Meanwhile over the same span, the L.A. suburbs have added 600,000 residents. Jobs? Between 2000 and 2014, the core and inner ring, as well as older suburbs, lost jobs, U.S. Census data show, while newer suburbs and exurbs added jobs.

In our most recent ranking of the metro areas creating the most jobs, Los Angeles ranked a mediocre 42nd out of the 70 largest metro areas; San Francisco ranked first. That’s well behind places like Dallas, Seattle, Denver, Orlando, and even New York and Boston, cities that we once assumed would be left in the dust by L.A.

A New Tech Hub?

The emergence of Snap has led some enthusiasts to predict L.A.’s emergence as a hotbed of the new economy. And to be sure, there is a growing tech corridor in the Santa Monica-Marina area that may gradually gain critical mass. Talk of a growing confluence between tech and entertainment content -- the signature L.A. product -- and the proliferation of new entertainment venues, could position the area for future growth. At the same time, the presence of Elon Musk’s Space X in suburban Hawthorne, near LAX, has excited local boosters.

Yet despite these bright spots, Los Angeles’ current tech scene is almost piteously small. One consistent problem is venture capital. Despite the massive size of its economy, and huge population, Los Angeles garners barely 5% of the nation’s venture capital, compared to 40% for the Bay Area, 10% for New York and Boston. Companies that were born in L.A. often end up moving elsewhere, like virtual reality pioneer Oculus, which was frog marched to the Bay Area after being acquired by Facebook.

Indeed, despite bright spots like Snap, since 2001 STEM employment in the L.A. metro area has been flat, in sharp contrast to high rates of job growth in the San Francisco Bay Area, Austin, Houston and Dallas, and the 10% national increase. Tech employment per capita in the L.A. area hovers slightly below the national average, according to a recent study I conducted at Chapman University. Los Angeles County, once the prodigious center of American high-tech, is also now slightly below the national average of engineers per capita.

The Poverty Economy

The regional economy, notes a recent Los Angeles Development Corporation report, continues to produce largely numbers of low-wage jobs, mostly in fields like health, hospitality and services. Sixty percent of all new jobs in the area over the next five years will require a high school education or less, the report projects.

At the same time in the year ending last September, employment dropped in three key high-wage blue collar sectors: manufacturing, construction and wholesale trade notes the EDC The largest gains were in lower-wage industries like health care and social assistance, hospitality and food service. Since 2007 Los Angeles County has 89,000 fewer manufacturing jobs, which pay an average of $54,000, but 89,000 more in food service that pay about $20,000. No surprise more than one out every three L.A. households have an income under $45,000 a year.

All this works well for the people who are increasingly coming to enjoy L.A.’s great restaurants, hipster enclaves and art venues. The football teams will add to this mixture, offering employment selling peanuts, popcorn and hot dogs to generally affluent fans in the stands.

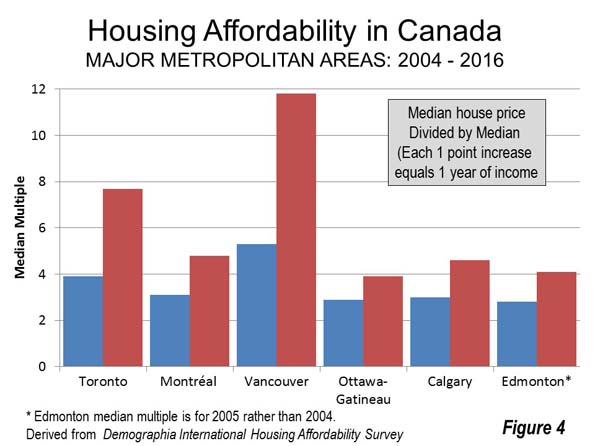

Yet low wages could prove catastrophic in a region that lags only the Bay Area in housing costs. Some 45,000 are homeless throughout the metro area, concentrated downtown but spreading throughout the region all the way to Santa Ana, in the south. Housing prices have risen to five times median household income, highest in the nation and more than twice the multiple in New York, Chicago, Houston or Dallas-Ft. Worth. L.A. leads the nation’s big metro areas in a host of other negative indicators, including the percentage of income spent on housing, overcrowding and homelessness. A city which once epitomized middle class upward mobility is increasingly bifurcated between a wealthy elite, mostly Anglo and Asian, and a largely poor Latino and African-American community.

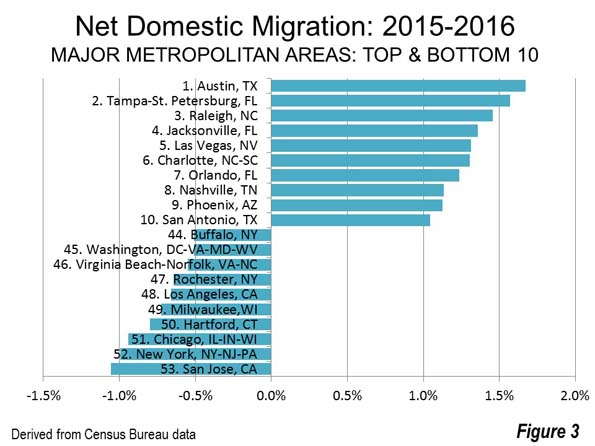

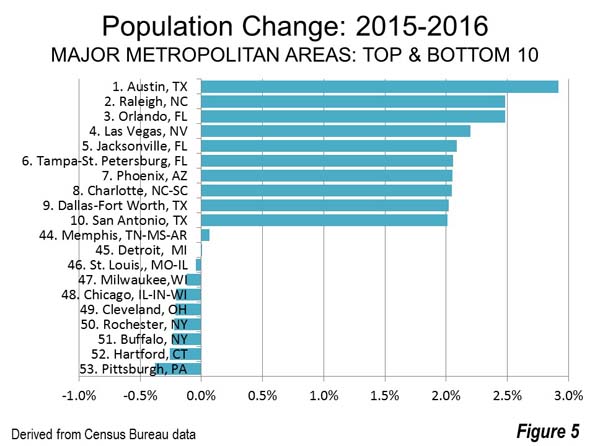

A recent United Way study, for example, found that 37% of L.A. families can barely make ends meet, well above the 31% average for the state; the core city’s south and east sides have among the largest concentrations of extreme poverty in the state. Once a beacon for migrants from all over America, L.A. now has a similarly high rate of mass out-migration as New York. But unlike New York, where immigrants continue to pour in, newcomers to the U.S. are increasingly avoiding Los Angeles – it had the lowest growth in its immigrant population of any major metropolitan area over the past decade. Perhaps even more revealing, the Los Angeles area has endured among the largest drops in the number of children since 2000,notes demographer Wendell Cox, more than New York, Chicago and San Francisco.

Altered DNA

The writer Scott Timberg notes that L.A.’s middle class, was once “the envy of the world.” L.A. used to be a place where firemen, cops and machinists could own houses in the midst of a great city. Dynamic, large aerospace firms, big banks and giant oil companies sustained the middle class.

But the city has lost numerous major employers over the years, most recently longtime powerhouse Occidental Petroleum, and the U.S. headquarters of both Toyota and Nestle. The regional aerospace industry, which provided nearly 300,000 generally high-wage jobs in 1990, is now barely a third that size. High housing cost have devastated millennials, whose home ownership rate has dropped 30% since 1990, twice the national average.

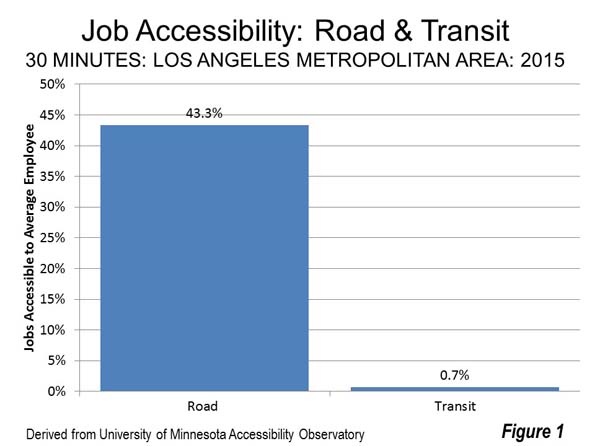

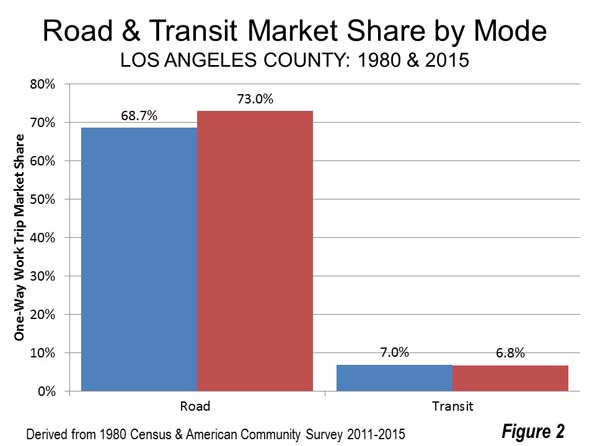

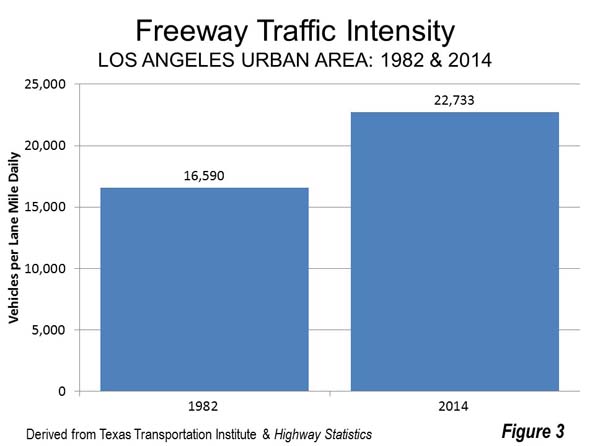

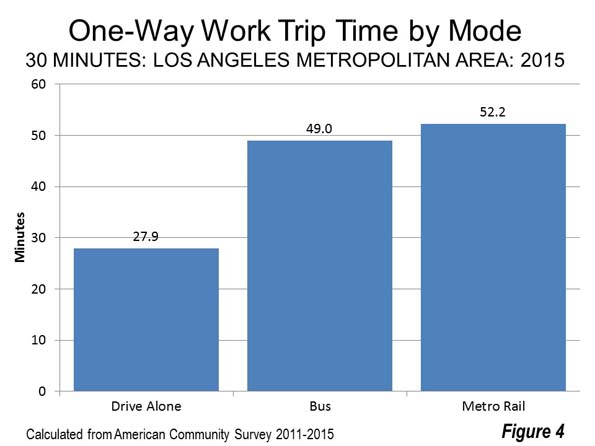

Many urbanists hail the emergence of a transit-oriented, dense city. Since 1990, Los Angeles County has added seven new urban rail lines and two exclusive busways at the cost of some $16 billion. Yet ridership on the Metropolitan Transportation Authority rail and bus services is now less than its predecessor Southern California Rapid Transit District bus services in 1985, before any rail services were opened. The share of work trips on transit in the entire five-county Los Angeles metropolitan region, has also dropped, from 5.1% in 1980 and 4.5% in 1990 to 4.2% in 2015. Meanwhile the city endures the nation’s worst traffic.

Some longtime Angelenos are mounting a fierce ballot challenge -- known as Measure S -- to slow down ever more rapid densification. The ballot measure would bar new high-density construction projects for the next two years. “The Coalition to Preserve L.A.,” which is funding the measure, claims to be leading in the polls for the March 7 vote, but faces well-financed opposition from politically connected large developers, Mayor Garcetti, both political parties, virtually the entire city council, and much of the academic establishment. The L.A. Times denounced Proposition S as a “childish middle finger to City Hall” and its architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne, has urged the citizenry “to move past the building blocks of post-war Los Angeles, including the private car, the freeway, the single-family house and the lawn.”

Proposition S proponents include many neighborhood and environmental groups, as well progressives and conservatives, including former Mayor Richard Riordan. The people controlling Los Angeles may dream of being the “next” New York but many residents, notes longtime activist Joel Fox, “are tired of the congestion and development and feel that more building will only add to congestion.”

Renewing La La Land

Of course, slowing or banning development by popular proposition is probably not the ideal way to get control over the deteriorating situation. Yet it is clear that the current trajectory towards more dense housing is not addressing the city’s basic problems. Los Angeles, as the movie “La La Land” so poetically portrays, remains a “city of dreams” but that mythology is clearly being eroded by a delusional desire to be something else.

In my old middle-class neighborhood in the San Fernando Valley, heavily populated by people from the creative industry, the worsening congestion, the upsurge of ever taller buildings and ever more present homeless did not reflect the giddiness of “La La Land.”

Yet despite all these problems, Los Angeles has the potential to make a great comeback. It has a dispersed urban form that allows for innovation and diversity, and an unparalleled physical location on the Pacific Rim. Its ethnic diversity can be an asset, if somehow it can generate higher wage employment to stop the race to the bottom. The basics are all there for a real resurgence, if the city fathers ever could recognize that the City of Angels needs less a new genome but should build on its own inimitable DNA.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us, was published in April by Agate. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Photo: AdamPrzezdziek