Yes, Jay Gould was a bad guy. But at least he helped build societal wealth. Not so our Silicon Valley overlords. And they have our politicians in their pockets.

A decade ago these guys—and they are mostly guys—were folk heroes, and for many people, they remain so. They represented everything traditional business, from Wall Street and Hollywood to the auto industry, in their pursuit of sure profits and golden parachutes, was not—hip, daring, risk-taking folk seeking to change the world for the better.

Now from San Francisco to Washington and Brussels, the tech oligarchs are something less attractive: a fearsome threat whose ambitions to control our future politics, media, and commerce seem without limits. Amazon, Google, Facebook, Netflix, and Uber may be improving our lives in many ways, but they also are disrupting old industries—and the lives of the many thousands of people employed by them. And as the tech boom has expanded, these individuals and companies have gathered economic resources to match their ambitions.

And as their fortunes have ballooned, so has their hubris. They see themselves as somehow better than the scum of Wall Street or the trolls in Houston or Detroit. It’s their intelligence, not just their money, that makes them the proper global rulers. In their contempt for the less cognitively gifted, they are waging what The Atlantic recently called “a war on stupid people.”

I had friends of mine who attended MIT back in the 1970s tell me they used to call themselves “tools,” which told us us something about how they regarded themselves and were regarded. Technologists were clearly bright people whom others used to solve problems or make money. Divorced from any mystical value, their technical innovations, in the words of the French sociologist Marcel Mauss, constituted “a traditional action made effective.” Their skills could be applied to agriculture, metallurgy, commerce, and energy.

In recent years, like Skynet in the Terminator, the tools have achieved consciousness, imbuing themselves with something of a society-altering mission. To a large extent, they have created what the sociologist Alvin Gouldner called “the new class” of highly educated professionals who would remake society. Initially they made life better—making spaceflight possible, creating advanced medical devices and improving communications (the internet); they built machines that were more efficient and created great research tools for both business and individuals. Yet they did not seek to disrupt all industries—such as energy, food, automobiles—that still employed millions of people. They remained “tools” rather than rulers.

With the massive wealth they have now acquired, the tools at the top now aim to dominate those they used to serve. Netflix is gradually undermining Hollywood, just as iTunes essentially murdered the music industry. Uber is wiping out the old order of cabbies, and Google, Facebook, and the social media people are gradually supplanting newspapers. Amazon has already undermined the book industry and is seeking to do the same to apparel, supermarkets, and electronics.

Past economic revolutions—from the steam engine to the jet engine and the internet—created in their wake a productivity revolution. To be sure, as brute force or slower technologies lost out, so did some companies and classes of people. But generally the economy got stronger and more productive. People got places sooner, information flows quickened, and new jobs were created, many of them paying middle- and working-class people a living wage.

This is largely not the case today. As numerous scholars including Robert Gordon have pointed out, the new social-media based technologies have had little positive impact on economic productivity, now growing at far lower rates than during past industrial booms, including the 1990s internet revolution.

Much of the problem, notes MIT Technology Review editor David Rotman, is that most information investment no longer serves primarily the basic industries that still drive most of the economy, providing a wide array of jobs for middle- and working-class Americans. This slowdown in productivity, notes Chad Syverson, an economist at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, has decreased gross domestic product by $2.7 trillion in 2015—about $8,400 for every American. “If you think Silicon Valley is going to fuel growing prosperity, you are likely to be disappointed,” suggests Rotman.

One reason may be the nature of “social media,” which is largely a replacement for technology that already exists, or in many cases, is simply a diversion, even a source oftime-wasting addiction for many. Having millions of millennials spend endless hours on Facebook is no more valuable than binging on television shows, except that TV actually employs people.

At their best, the social media firms have supplanted the old advertising model, essentially undermining the old agencies and archaic forms like newspapers, books, and magazines. But overall information employment has barely increased. It’s up 70,000 jobs since 2010, but this is after losing 700,000 jobs in the first decade of the 21st century.

Tech firms had once been prodigious employers of American workers. But now, many depend on either workers abroad of imported under H-1B visa program. These are essentially indentured servants whom they can hire for cheap and prevent from switching jobs. Tens of thousands of jobs in Silicon Valley, and many corporate IT departments elsewhere, rent these “technocoolies,” often replacing longstanding U.S. workers.

Expanding H-1Bs, not surprisingly, has become a priority issue for oligarchs such as Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, and a host of tech firms, including Yahoo, Cisco Systems, NetApp, Hewlett-Packard, and Intel, firms that in some cases have been laying off thousands of American workers. Most of the bought-and-paid-for GOP presidential contenders, as well as the money-grubbing Hillary Clinton, embrace the program, with some advocating expansion. The only opposition came from two candidates disdained by the oligarchs, Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump.

Now cab drivers, retail clerks, and even food service workers face technology-driven extinction. Some of this may be positive in the long run, certainly in the case of Uber and Lyft, to the benefit of consumers. But losing the single mom waitress at Denny’s to an iPad does not seem to be a major advance toward social justice or a civilized society—nor much of a boost for our society’s economic competitiveness. Wiping out cab drivers, many of them immigrants, for part-time workers driving Ubers provides opportunity for some, but it does threaten what has long been one of the traditional ladders to upward mobility.

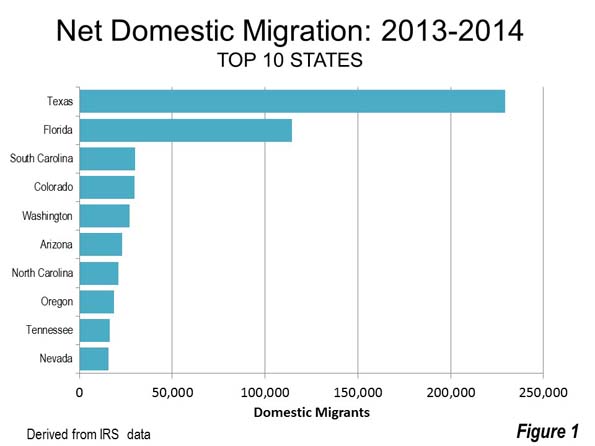

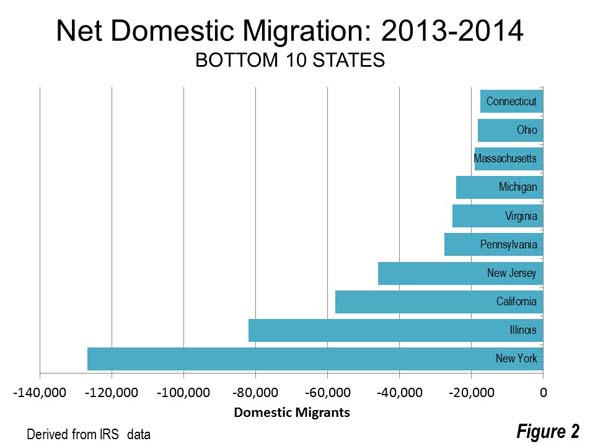

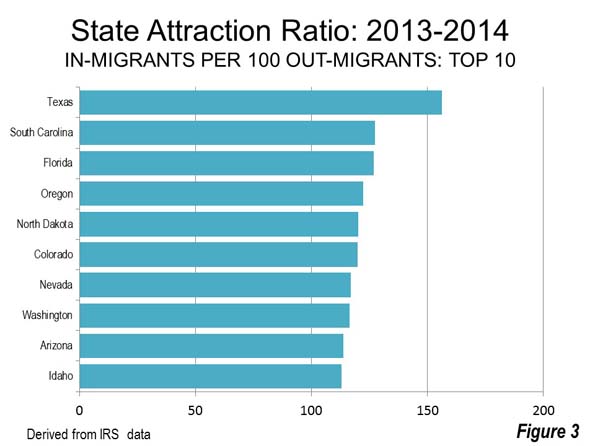

Then there is the extraordinary geographical concentration of the new tech wave. Previous waves were much more highly dispersed. But not now. Social media and search, the drivers of the current tech boom, are heavily concentrated in the Bay Area, which has a remarkable 40 percent of all jobs in the software publishing and search field. In contrast, previous tech waves created jobs in numerous locales.

This concentration has been two-edged sword, even in its Bay Area heartland. The massive infusions of wealth and new jobs has created enormous tensions in San Francisco and its environs. Many San Franciscans, for example, feel like second class citizens in their own city. Others oppose tax measures in San Francisco that are favorable to tech companies like Twitter. There is now a movement on to reverse course and apply “tech taxes” on these firms, in part to fund affordable housing and homeless services. Further down in the Valley, there is also widespread opposition to plans to increase the density of the largely suburban areas in order to house the tech workforce. Rather than being happy with the tech boom, many in the Bay Area see their quality of life slipping and upwards of a third are now considering a move elsewhere.

Once, we hoped that the technology revolution would create ever more dispersion of wealth and power. This dream has been squashed. Rather than an effusion of start-ups we see the downturn in new businesses. Information Technology, notes The Economist, is now the most heavily concentrated of all large economic sectors, with four firms accounting for close to 50 percent of all revenues. Although the tech boom has created some very good jobs for skilled workers, half of all jobs being created today are in low-wage services like retail and restaurants—at least until they are replaced by iPads and robots.

What kind of world do these disrupters see for us? One vision, from Singularity University, co-founded by Google’s genius technologist Ray Kurzweil, envisions robots running everything; humans, outside the programmers, would become somewhat irrelevant. I saw this mentality for myself at a Wall Street Journal conference on the environment when a prominent venture capitalist did not see any problem with diminishing birthrates among middle-class Americans since the Valley planned to make the hoi polloi redundant.

Once somewhat inept about politics, the oligarchs now know how to press their agenda. Much of the Valley’s elite–venture capitalist John Doerr, Kleiner Perkins, Vinod Khosla, and Google—routinely use the political system to cash in on subsidies, particularly for renewable energy, including such dodgy projects as California’s Ivanpah solar energy plant. Arguably the most visionary of the oligarchs, Elon Musk, has built his business empire largely through subsidies and grants.

Musk also has allegedly skirted labor laws to fill out his expanded car factory in Fremont, with $5-an-hour Eastern European labor; even when blue-collar opportunities do arise, rarely enough, the oligarchs seem ready to fill them with foreigners, either abroad or under dodgy visa schemes. Progressive rhetoric once used to attack oil or agribusiness firms does not seem to work against the tech elite. They can exploit labor laws and engage in monopoly practices with little threat of investigation by progressive Obama regulators.

In the short term, the oligarchs can expect an even more pliable regime under our likely next president, Hillary Clinton. The fundraiser extraordinaire has been raising money from the oligarchs like Musk and companies such as Facebook. Each may vie to supplant Google, the company with the best access to the Obama administration, over the past seven years.

What can we expect from the next tech-dominated administration? We can expect moves, backed also by corporate Republicans, to expand H-1B visas, and increased mandates and subsidies for favored sectors like electric cars and renewable energy. Little will be done to protect our privacy—firms like Facebook are determined to limit restrictions on their profitable “sharing” of personal information. But with regard to efforts to break down encryption systems key to corporate sovereignty, they will defend privacy, as seen in Apple’s resistance to sharing information on terrorist iPhones. Not cooperating against murderers of Americans is something of fashion now among the entire hoodie-wearing programmer culture.

One can certainly make the case that tech firms are upping the national game; certain cab companies have failed by being less efficient and responsive as well as more costly. Not so, however, the decision of the oligarchs–desperate to appease their progressive constituents–to periodically censor and curate information flows, as we have seen at Twitter and Facebook. Much of this has been directed against politically incorrect conservatives, such as the sometimes outrageous gay provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos.

There is a rising tide of concern, including from such progressive icons as former Labor Secretary Robert Reich, about the extraordinary market, political, and culture power of the tech oligarchy. But so far, the oligarchs have played a brilliant double game. They have bought off the progressives with contributions and by endorsing their social liberal and environmental agenda. As for the establishment right, they are too accustomed to genuflecting at mammon to push back against anyone with a 10-digit net worth. This has left much of the opposition at the extremes of right and left, greatly weakening it.

Yet over time grassroots Americans may lose their childish awe of the tech establishment. They could recognize that, without some restrictions, they are signing away control of their culture, politics, and economic prospects to the empowered “tools.” They might understand that technology itself is no panacea; it is either a tool to be used to benefit society, increase opportunity, and expand human freedom, or it is nothing more than a new means of oppression.

This piece first appeared in The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us, will be published in April by Agate. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Official White House Photo by Pete Souza.

![]()

, and

, and