At the site of real and immediate tragedy, an old man comes, wielding not a sword to protect civilization from ghastly present threats but to preach the sanctity of California’s green religion. The Paris Climate Change Conference offers a moment of triumph for the 77-year-old Jerry Brown, the apogee of his odd public odyssey.

Jerry Brown has always been essentially two people—one the calculating, Machiavellian politician, the other the dour former Jesuit who publically dismisses worldly pleasures for austere dogma. Like a modern-day Torquemada, he is warning the masses that if they fail to adhere in all ways of the new faith or face, as he suggested recently humanity’s “extinction.”

Brown is important because many other green cheerleaders like Al Gore grate on the public, in part because of rampant greed and a penchant for unsupportablepredictions. In contrast, Brown presents, with some justification, the very model of enlightened leadership and smart management, certainly in comparison with the ideologues and public employee pawns who dominate his party, and the blatant wealthy hypocrites who rule the green universe.

Increasingly, Brown has become the patron saint of climate change, while at the same time exposing the effort’s flaws and contradictions most clearly. Railing against the satanic greenhouse gases, Brown, one supposes unwittingly, seems unconcerned he is waging what amounts to a war against the state’s own middle and working classes. His intolerance of dissent—albeit less extreme than some—reflects the current trajectory of environmentalism, which increasingly seeks to silence and even criminalize those who dispute their analyses and prescriptions.

Like the Spanish father of the Inquisition, Brown has it in for anyone who dissents from his “God is not mocked,” as he suggested recently, attacking critics of his policies as “falsifying the scientific record,” something climate change advocates have also been caught doing on more than one occasion. Brown dismisses allclimate skeptics, even those who admit some carbon-caused warming, as “a well funded cult.”

Like a religious adept, Brown shows his need to link everything to one sin—greenhouse gas emissions—to explain virtually everything from wildfires to the current drought on climate change, although with little support from scientists who study such things. As was common in the worst aspects of the medieval Catholic Church, one increasingly cannot dissent in any way from revealed doctrine without being essentially evil.

Between Image and Reality

In Paris, Brown hopes to present himself as the great green success story, leader of an economy that has thrived despite some of the world’s most draconian climate change measures. And he has something of a case since California, after suffering greatly in the recession, has finally recovered its lost jobs and has bolstered its critical role as the dominant technology power on the planet.

For many progressives, California represents “a beacon of hope.” Its “comeback” has been dutifully noted and applauded by left-wing economist Paul Krugman, and Michael Kinsley and the Washington Post’s Chris Cilizza have even suggested that Brown should run for president—at the ripe age of 77.

These fans miss a big part of the reality. Outsiders think of California as a prosperous place that mints billionaires, but overall the state’s economic recovery has done little for many, if not most, state residents. Even with the boom in Silicon Valley, roughly one in three Californians live check to check, the state hashigher rate of poverty than Mississippi, as well as one-third of the nation’s welfare recipients. Among the emerging Latino majority, a prime Brown constituency, the state’s cost-adjusted poverty rate is more than 33 percent, compared to just 22.7 percent in Texas, a state often derided as unenlightened and cruel.

During this “boom,” most California blue-collar workers in farming, fishing, and forestry have experienced actual average wage decreases. Employment in fields such as construction and manufacturing remain well below their 2007 levels. Much of this has to do with environmental regulation, which has raised energy costs almost twice those of nearby competitors and also helped raise housing prices to an unsustainable level.

Once the beacon of opportunity, California is becoming a graveyard of middle-class aspiration, particularly for the young. In a recent survey of states where “the middle class is dying,” based on earning trajectories for middle-income cohorts, Business Insider ranked California first, with shrinking middle-class earnings and the third-highest proportion of wealth concentrated in the top 20 percent.

Most hurt, though, are the poor. California is home to a remarkable 77 of the country’s 297 most “economically challenged,” cities based on levels of poverty and employment, according to a recent USC study; altogether these cities have a population of more than 12 million. Some stressed cities exist cheek-to-jowl with the state’s uber-rich—Oakland, Los Angeles, as well as Coachella, near Palm Springs. Most others are in the poorer, more heavily Latino interior, places like Riverside, Stockton, and Vallejo. Journalists who come to California to praise the governor may think it’s still “California Dreamin’” but for all too many, particularly away from the coast (PDF), it’s more like The Grapes of Wrath.

The Making of a Modern Medievalist

Of course, there’s a long history of such bifurcated society, where people tend to stay in their class and the poor depend largely on handouts from their spiritual “betters.” It’s called feudalism.

In many ways, Jerry Brown is a perfect medievalist—the son of a self-made man, a person who largely inherited his position. Without the legacy of his father, Edmund G. “Pat” Brown, a natural politician and arguably the greatest governor in the state’s history, it’s unlikely the shy, awkward, although unquestionably bright kid would have been elected the first time in his mid-thirties.

Brown came to politics bathed not in the practicum of politics but in theology. As a seminarian, he imbibed the Jesuitical approach—highly intellectualized, hierarchical, and accepting of class distinctions. Although he occasionally dabbled in populist politics, particularly in his presidential runs, Brown’s achievement has been to undermine not just the Reaganite regime but also the pro-growth progressive structure left behind by his father and earlier California governors.

Brown’s acuity has often been on target, as, for example, when he took on the encrusted bureaucracy at the University of California and inside state government. But Brown’s maverick approach also revealed a streak that reflected a harshness toward those who were weaker, including the poor. In his first term, Brown’s callous treatment of the mentally ill left 30,000 mental patients in worsening conditions in inadequate nursing facilities. As the Los Angeles director of mental health told me at the time, under Reagan there was “genuine concern for people,” while under Brown he didn’t “see much concern for people at all.”

He came into office, recalled top aide Tom Quinn, “questioning the values of the Democratic Party” and rejecting the “build, build, build thing” of his father. Like the 15th century Florentine Catholic monk Girolamo Savonarola, he came to Sacramento, in part, to rid it of suberbia and luxuria. Most important, he did not restart the infrastructure building, most portentously for water storage, that marked his father’s regime; the severity of the drought and the awful condition of the state’s roads are, to some extent, his legacy.

Brown’s initial politics were built around three principles—“serve the people, save the earth, and explore the universe.” Some, such as farmworkers, owe him much. But the biggest winners under Brown were the well-financed green lobby and public employee unions have become so powerful that that replaced the coalition of developers, farmers, and industrialists who had accepted, and often bankrolled, his father.

In recent years, Brown, after being praised for his moderation in his first four years as second time governor, has become more “crotchety,” according to the Los Angeles Times’ George Skelton. He has insisted on funding his favorite project, the much maligned “bullet train,” even though many on the left, including Mother Jones, have identified it not as an environmental benefit but a colossal waste of time and money.

In contrast, on most everything else, Brown leans toward austerity—he even reveals a fondness for the ration cards used during World War II. Yet surprisingly, Brown, the supposed ascetic, appears increasingly comfortable with his own wealth. He has speculated freely in Bay Area real estate and stocks, essentially creating a multimillion-dollar estate that, as the San Jose Mercury put it kindly, “belie [the] monastic image.” Recently he shocked his own green supporters by having a state agency perform a detailed analysis of the oil, gas, and mineralresources on his family’s 2,700-acre Northern California ranch, a service not readily available to other mere mortals.

As for the poor left behind in California’s recovery, this, Brown insists, is not due to policy failure but because the state is an irresistible “magnet” for the masses.

The High Priest of the Oligarchy

Early on Brown cleverly cultivated the emerging tech oligarchy in Silicon Valley. This has created a new class of major donors who, along with the unions and Hollywood, have financed his political re-ascendency.

The oligarchs seem kindred souls for Brown, with little patience for less advanced beings. He also knew that their success has allowed him to show economic gains without having to concede to the regulatory concerns of more traditional industries. In the new Silicon Valley, most of the “dirty work” is shoved off to other more benighted states, or abroad; regulatory overreach poses only limited problems. For his part, Brown sees the oligarchs as the state’s economic foundation. “We’ve got a few problems, we have lots of little burdens and regulations and taxes,” he said recently, “but smart people figure out how to make it.”

Brown’s Bay Area connection is helped by the fact that the venture and tech firm oligarchy often share his climate concerns. He has further tightened this alliance by lavishing enormous subsidies for often dodgy, expensive renewable energy schemes backed by companies such as Google and by many among the venture capitalist elite.

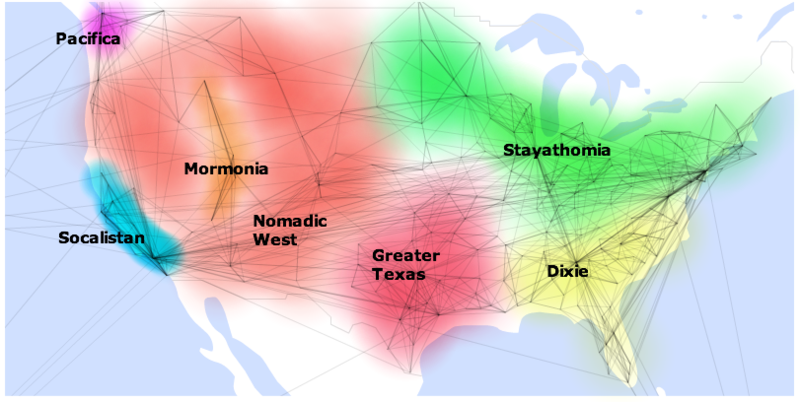

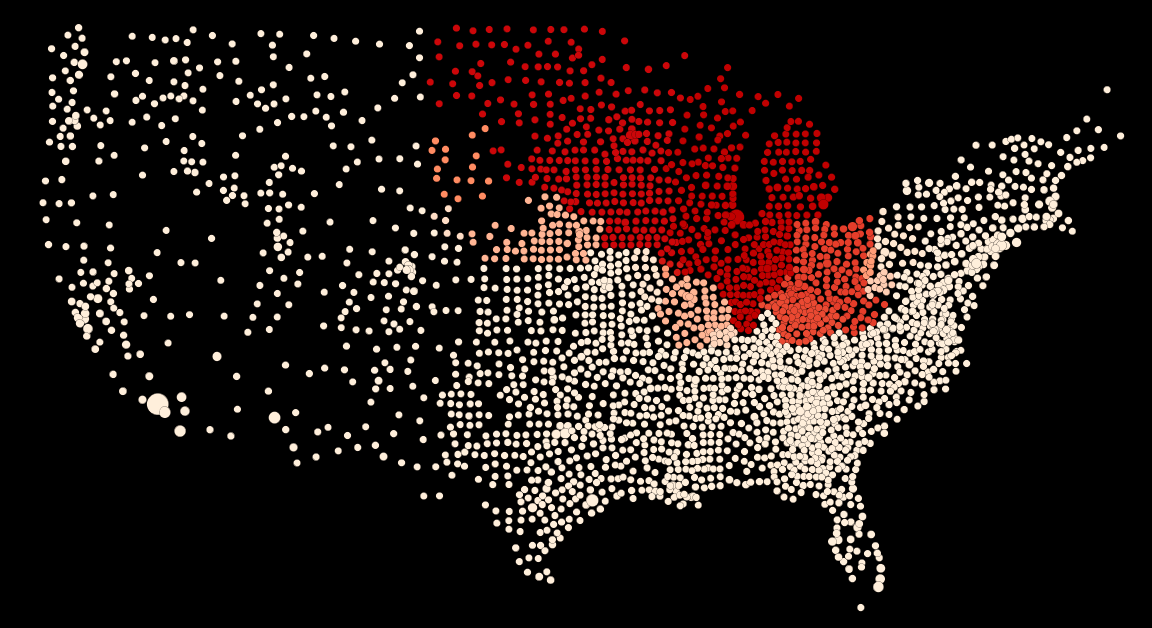

Ironically, none of Brown’s moves will, by themselves, have any demonstrable impact on climate. California is too small, too temperate, and, at this stage, too de-industrialized to make a difference. Indeed, as one recent study found, California could literally disappear tomorrow with virtually no effect on the climate. Perhaps less recognized, its efforts to reduce emissions have accounted for naught, since so much industry and so many people—some 2 million in the last decade—have taken their carbon footprint elsewhere, usually to places where climate and less stringent regulation allow for greater emissions. Some states, rather than embrace Brown’s formula and seeing an opportunity to score, have detached themselves from renewable mandates entirely.

And now the world

So why the dogged insistence on draconian policies? It’s very much for the same reason people take priestly vows, or why penitents whip themselves: moral posturing before the rest of the world and, for politicians, the prospect of attracting the adoring masses (or at least the media). President Obama looks to California policies for his future climate policies. On this issue Brown is the rock star, and will be in Paris, cool again after all these years.

Brown’s green religion now has a most powerful ally, the leading Jesuit on the planet, Pope Francis. This alliance offers something of a religious redemption for Brown, a former seminarian who has rejected most traditional Catholic teachings on such things as gay marriage, abortion, population control, and, most recently,euthanasia.

In Paris, Brown’s claims of economic infallibility should be questioned particularly among leaders of developing countries. Some 3 billion people suffer from pollution created by burning wood, coal, or dung. Some 4.3 million die annually from the resultant indoor pollution compared to 250,000 deaths that might be assigned to climate change by 2050. For many, fossil fuels represent a lifesaver today. To offer these people expensive and inefficient solar panels instead of basic necessities, as economist Bjorn Lonborg has suggested, represents nothing more than “inexcusable self-indulgence.”

Some developing countries are making their intentions clear. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has thrown out Greenpeace for agitating against coal mines in his energy-starved country. China, whose world-leading emissions are now almost twice those of the U.S., recently admitted to burning 17 percent more coal than previously estimated. No doubt they will happily wink and nod their assent to a vague green agreement while Western countries, following Brown, Obama, and the Pope, adopt ever stricter regulations. By the time we get to 2030, when China might begin reducing emissions, the West itself may be so weakenedeconomically that it won’t be able to question anything Beijing wants to do anyway.

Russia and virtually the entire Middle East also are not likely to give up on fossil fuels, which is the only thing that makes the world pay attention to them. Rather than use our energy boom to create leverage against these autocracies, Brown and his confederates are pushing policies that consequently make them more influential, also allowing them to finance and arm terrorists, whether ISIS, al Qaeda, or theocratic Iran and their satraps.

A decade from now, the futility and wasted economic potential of this posturing will be clear. What could have been accomplished, at least initially, by replacing coal with natural gas and the careful expansion of nuclear power, will instead lead to a lower quality of life for all but the rich in the West, with perhaps worse ill-effects elsewhere. But by then Brown will likely have faded from the scene, although he may manage to get his wife, former Gap attorney Ann Gust Brown, elected to succeed him.

What will be Brown’s main legacy? A more environmentally pure but severely bifurcated California and, if he and his compatriots have their way, an accelerating decline of the Western world and arguably the stagnation of the entire world economy. But Brown and his crony capitalist and priestly friends will be happy. They may have messed up the world, but they will always have Paris.

Photo: Troy Holden

![]()

, a collection of historical travel essays, and

, a collection of historical travel essays, and