THis is the overview from a new report, Best Cities for Minorities, Gauging the Economics of Opportunity by Joel Kotkin and Wendell Cox for the Center for Opportunity Urbanism. Read the full report here (pdf viewer).

This study provides an initial analysis of African-American, Latino and Asian economic and social conditions in 52 metropolitan regions currently and over the period that extends from 2000 to 2013. Our analysis includes housing affordability, median household incomes, self-employment rates, and population growth. Overall, the analysis shows that ethnic minorities in metropolitan regions with significant economic growth and affordable housing tend to do better than in other locations irrespective of the dominant political culture.

Understanding the dynamics of minority economic mobility is critical to the future of all Americans. If ethnic minorities may once have been viewed as a cultural afterthought in a primarily anglo society, they are

now unquestionably America’s future. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, minority children will outnumber white children by as early as 2020, and by 2050, non-white ethnic groups will equal the total number of White-non Hispanics in the population. These estimates likely understate the rate of ethnic transformation in the U.S. because of the country’s growing number of mixed race households.

For years America has been an anglo-dominated nation and ethnic groups largely peripheral societies all too frequently marginalized by discrimination, segregation and racial strife. If W.E.B. Dubois famously noted that “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line” at the beginning of the 20th century,” the great historian John Hope Franklin asserted that racial issues will continue to shape our society in the 21st.

Demographic trends suggest this is inevitable. Today, America’s ethnic population has surged to an unprecedented extent Latinos, together with African Americans and Asians, now constitute 43 percent of the population

in the country’s 52 largest metropolitan areas with a population of at least one million residents, which also comprise 55 percent of the total U.S. population. This is up from 35 percent in 2000.

African Americans, including new immigrants from the Caribbean and Africa, constitute 15 percent of the population, Hispanics are now 21 percent and Asians 7 percent. These areas. Today Latinos are the nation’s largest ethnic minority and Asians the fastest growing in percentage terms.

Despite the massive new and growing influence of ethnic minorities, there are surprisingly few studies comparing the economic performance of American’s burgeoning communities in different metropolitan areas. Fewer still have attempted to identify specific factors that correlate with the most and least favorable results in different regions. As the ethnic composition of America decisively shifts, it is vitally important to understand what regional factors work best to create and sustain economic and social opportunities for the nation’s emerging majority groups.

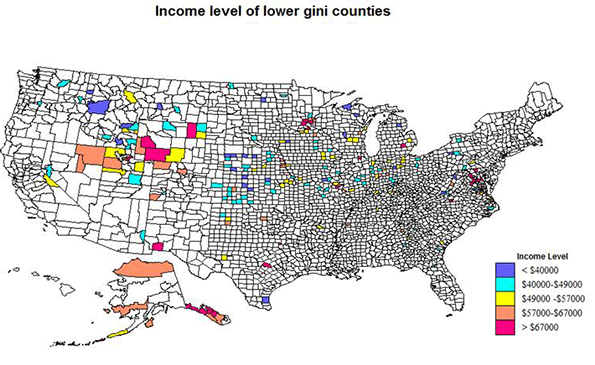

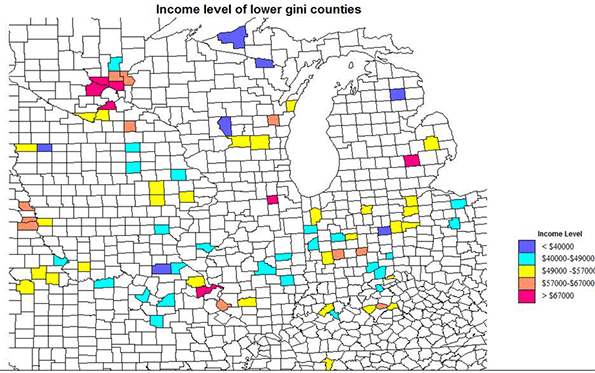

Overall we found that metropolitan areas with less burdensome regulations, especially those affecting land use and housing costs, tended to do better, in the survey, but not in every instance. Some areas with more restrictive regulations were also highly ranked if other factors, such as a proximity to a relatively robust government employment base (Washington D.C. and Baltimore regions), or rapid private sector growth (Asians in the San Jose area) were sufficiently strong to overcome adverse regulatory and tax burdens.

The data also show a strong contrast between America’s luxury cities, such as New York, San Francisco or Boston, where high costs have significantly reduced opportunities for middle and working class households, and “opportunity cities,” often located in less costly portions of the country like Texas or the South but that have also sustained more rapid and broadly based economic growth.

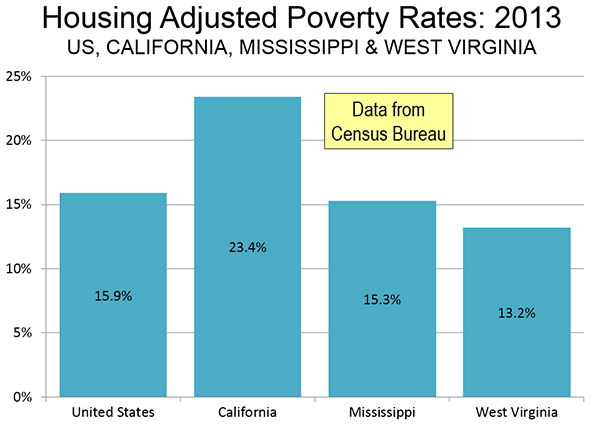

Although most, if not all, luxury cities sustain strongly progressive politics African-Americans, Asians and Latino households have done relatively worse in these locations; cities in the states with the more generous welfare provisions aimed to help the minority poor - notably California, New York and Illinois - tended to perform worse than those that were less forthcoming, notably in the sunbelt. Ironically, in many of these places, such as metropolitan New York, Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles, the media and public officials may be the most adamant in attacking racial and class inequality, but their outcomes have been generally less than optimal.

Instead, America’s ethnic population growth, has shifted away from these slower growth, higher cost regions, irrespective of the level of public assistance or political ideology, towards opportunity cities where economic, housing and other policies provide greater chances of social advancement for middle and working class Americans of all races.

The implication of these findings is that America’s emerging majorities, like the Anglo communities before them, primarily desire and will populate regions where they can afford decent homes, earn higher incomes relative to the cost of living, and have greater independence and opportunity, as reflected in self-employment rates. These broad strategies do much more to enhance the lives of African-Americans, Asians and Latino households than the redistributive war on poverty-era programs employed in regions with high housing and living costs. These programs are usually not sufficient to improve the prospects of minorities if the business environment is burdened by high costs and regulatory burdens.

Minorities Head to Opportunity Cities

The data overwhelmingly show that minority populations are growing much faster in opportunity cities than in the more expensive, highly regulated luxury cities in the Northeastern corridor or on the west coast.iv In some cases, this has to do with the changing post-industrial nature of these economies. The increasing dependence on industries, such as software and social media, that employ few Latinos or African Americans. In Silicon Valley, African Americans and Hispanics make up roughly one-third of the valley population but barely five percent of employees in the top Silicon Valley firms.

Over the past forty years States such as Texas, Arizona, the Carolinas and Florida have seen their employment base grow far more rapidly and broadly in terms of manufacturing and other blue collar sectors than either California or the Northeast corridor.vi Generally, the leading metropolitan areas in the sunbelt also have overall enjoyed higher growth in population, income and self- employment and considerably higher rates for minority homeownership. “Luxury cities” such as described by

former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg are generally not so good for minorities.

Read the full report (pdf viewer).

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is also executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is also author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He was appointed to the Amtrak Reform Council to fill the unexpired term of Governor Christine Todd Whitman and has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.