“Human happiness,” the Greek historian Herodotus once observed, “does not abide long in one place.” In its 240 years or so of existence, the United States has experienced similar ebbs and flows, with Boston replaced as the nation’s commercial capital first by Philadelphia and then by New York. The 19th century saw the rise of frontier settlements—Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and finally Chicago—that also sought out the post position. In the mid 20th century, formerly obscure Los Angeles emerged as New York’s most potent rival.

Today we are seeing yet another shuffling of the deck among American regions. New York remains the country’s preeminent city, but its most powerful rivals are likely to be neither Chicago nor Los Angeles, but rather two regions rarely listed in the hierarchy of influential regions: the San Francisco Bay Area and Houston.

Making of a new pecking order

The Bay Area does not rank among the 20 top global cities in most studies, such as the 2014 A.T. Kearney listings. In the respected rankings of the London-basedGlobalization and World Cities Network, the Bay Area stood below not only Chicago, which is considered an “alpha” global city, but also such places as Toronto and Mexico City.

Yet such rankings vastly underestimate the power now being wielded by the San Francisco region. As the headquarters for the largest concentration of cutting edge tech firms in the world, the Bay Area increasingly shapes the operations of companies from manufacturing and marketing to retail and media. And given that roughly half the nation’s venture capital is still being lavished on area start-ups, it is not surprising that Silicon Valley ranks number one in the world as a place to launch tech ventures, according to the Startup Genome.

Tech dominance, according to a recent study on global cities conducted by my firm NewGeography, explains why the San Francisco Bay Area nudges out much larger Los Angeles for bragging rights on America’s Pacific Rim. Technology leaders, including Intel, Apple, Oracle, Google, and Facebook, are based in Silicon Valley, while Asian global tech firms such as Samsung also have North American headquarters there. Top technology firms from other cities often have their key R&D functions in the Bay Area. Even a frugal firm like Wal-Mart is enlarging its Silicon Valley presence.

The current social media bubble will surely pop, but as Michael S. Malone and others have noted, the Bay Area’s preeminence will likely continue, fueled by its unique concentration of engineers, entrepreneurs, and risk capital. As a lure for the ambitious, Silicon Valley and San Francisco are replacing Wall Street. Google alone has 1,200 employees who formerly worked for large U.S. investment banks, and migration from the Big Apple to California is now at its highest level since 2006.

Much of the appeal of the Bay Area is a result of happy coincidence of history and geography. The Bay Area—where I went to school and got my start in journalism, and where parts of my family have resided since the ’50s—has been blessed with excellent higher education and is centered around what is arguably America’s most beautiful city. Good weather, beautiful vistas, and access to nature have made the Bay Area a natural lure for people who can afford to live wherever they want.

The Energy Capital

Houston, where I have been working as a consultant, hardly qualifies as one of the most physically attractive or temperate cities. San Francisco may well have been, as Neil Morgan suggested a half century ago, “the Narcissus of the West,” but Houston, in most accounts, has been widely disparaged as hot, steamy, ugly and featureless. Yet despite this, its ascendency is no less compelling than that of the Bay Area.

Houston’s trump card, like the Bay Area’s, resides in its control of one strategic industry, in this case energy. The majority of traded foreign oil majors, such as London-based Shell and British Petroleum, have their U.S. headquarters in Houston, and even companies based elsewhere boast a significant Houston presence. For example, Exxon, although it has its headquarters in Dallas-Fort Worth, is opening a massive Houston campus that will be home to 10,000 employees. Additionally, a majority of the world’s largest oil services companies, such as Baker Hughes, Schlumberger, and FMC Technologies, are based in Houston.

Altogether, more than 5,000 energy-related companies call Houston home. The city employs three times more people in energy than its second place rival, Dallas-Ft. Worth, and more than the next five cities combined. This growth is likely to accelerate because foreign companies, notably from Germany, have begun buying up energy firms in the area, including Siemens’s recent $7.6 billion dollar purchase of the Dresser Rand Group, an energy equipment firm.

Houston has added more than 10 percent more jobs since 2008, almost twice the increase in the Bay Area. Since 2000 Houston’s employment figures have shot up 32 percent, while the Bay Area has grown by barely 4 percent. And it’s not just energy that’s driving things—Houston is now the nation’s largest export port and boasts the world’s largest medical center. It has also become, by some measurements, the most ethnically diverse (PDF) region in the country. In the last decade, for example, Houston increased its foreign-born population by 400,000, second only to New York and well ahead of much larger Los Angeles.

The big losers: LA and Chicago—but also New York

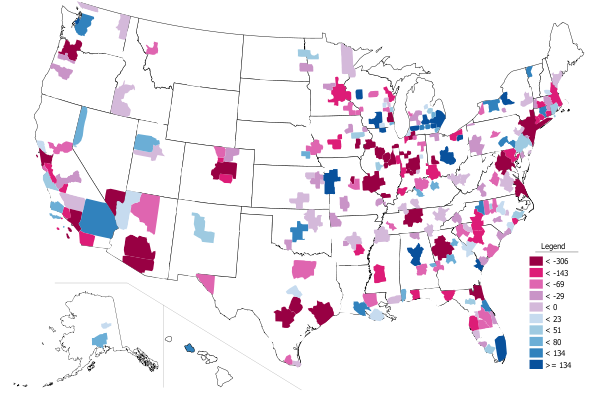

In the past century New York and Los Angeles have dominated American media. This is being severely undermined by the Bay Area’s digital economy. Since 2001, notes Mark Schill at Praxis Strategy (where I am a senior fellow), book, periodical, and newspaper publishing—all traditionally concentrated in the New York area—have lost some 250,000 jobs, while Internet publishing and portals generated some 70,000 new positions, many of them in the Bay Area or Seattle.

Google and Yahoo are already among the largest media companies in the world. (Yahoo now refers to itself as a digital media company rather than a technology company). With the ubiquity of its iTunes platform, Apple exercises ever greater control over consumer distribution of entertainment products such as music and video; Netflix, Hulu, and YouTube could become the studios of the future. This could shift global media decision-making from its familiar New York-Los Angeles axis to the Bay Area.

This is particularly bad news for Los Angeles, whose grip on the entertainment industry was weakening even before Silicon Valley’s rise. Since 2004, LA’sentertainment industry lost roughly 11 percent of its jobs, as production shifted to Canada, Louisiana, and other locales.

The decline in media employment comes on the heels of a rapid industrial decline—the area has lost more than 90,000 aerospace jobs since the end of the Cold War. The situation is so dismal that a report issued by many of the region’s top business and political leaders concluded that the city “is barely treading water while the rest of the world is moving forward.”

Chicago’s situation is arguably even worse, but it is more threatened by Houston, which has already passed the Windy City in numbers of corporate headquarters. Since 2010, when U.S. industry began recovering, Houston manufacturing employment expanded by more than 17 percent, compared to flat growth in Chicago.

“Houston is the Chicago of this era—like the old Chicago,” remarks David Peebles, who runs the Texas office of Odebrecht, a $45 billion engineering firm based in Brazil. “In the ’60s you had to go to Chicago, Cleveland, and Detroit. Now Houston is the place for new industry.”

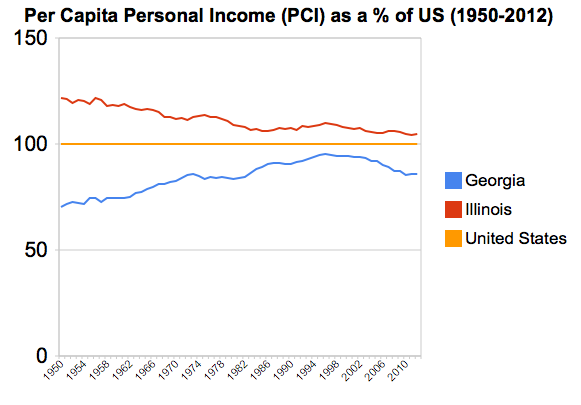

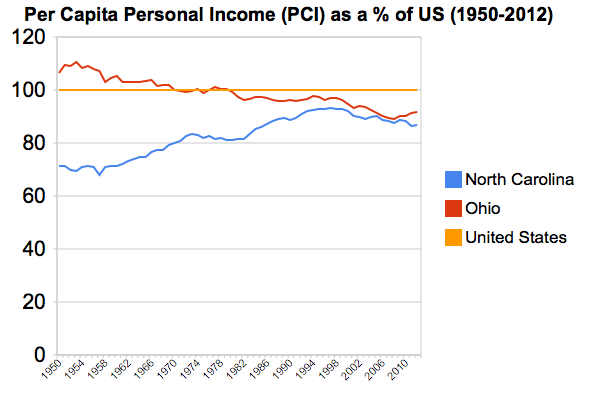

With its industrial base eroding, Chicago is no longer a strategic hub for any key industry. Outside of trading commodities, it also no longer serves as a major global financial center. Regional population growth has been meager over the past decade, and the city’s own pension issues may be worse than Detroit’s.

Chicago retains its brilliant skyline, great cultural institutions, powerful political influence, and a strong business community. But its days of America’s number two city are long gone, and, as we enter the mid-2000s, it is falling behind not only Los Angeles and New York but the two rising Texas cities, Houston and Dallas, both expected to pass the “city of big shoulders” in population by mid-century, or earlier.

Engineering the Future

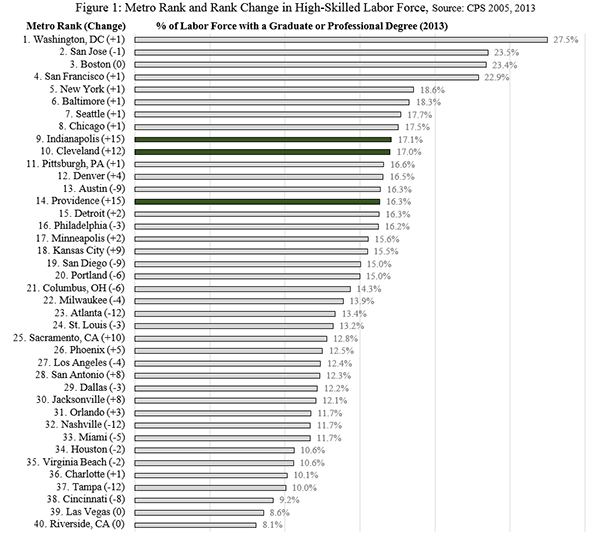

In the coming decades, New York will remain the nation’s top global city, due to its remarkable urban legacy, the power of Wall Street, and the entrenched traditional media. But its Achilles heel is a lack of the engineering power necessary to address key challenges such as the digitization of industry, energy efficiency or climate change. New York is profoundly weak in engineering talent (PDF)—ranking 78th out of 85 metropolitan areas in engineers per capita.

In contrast, the Bay Area represents the epitome of engineering power, with the San Jose area boasting the largest per capita concentration of engineers of any major metropolitan area. The Bay Area’s power to develop new technologies and its almost unfathomable wealth will continue to undermine traditional institutions, from Hollywood and Wall Street to business services, tourism, automotive, and even aerospace industries.

Far less appreciated, Houston, rather than being a southern city of duller wits, actually ranks second in engineers per capita. If the Bay Area is master of the digital economy, Houston ranks as the technological leader of the material one; it is the capital for the energy-driven revival of U.S. industry, not only in Texas but throughout the old industrial heartland. Revealingly, Houston actually has seen far more rapid growth in both college educated and millennial population since 2000 than the Bay Area, as well as New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles.

Rival Approaches to Urbanism

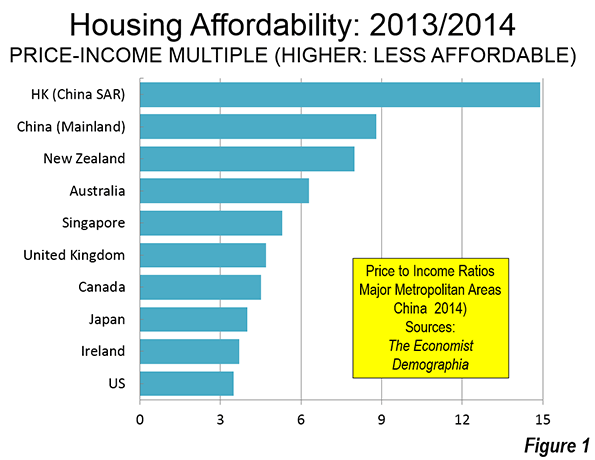

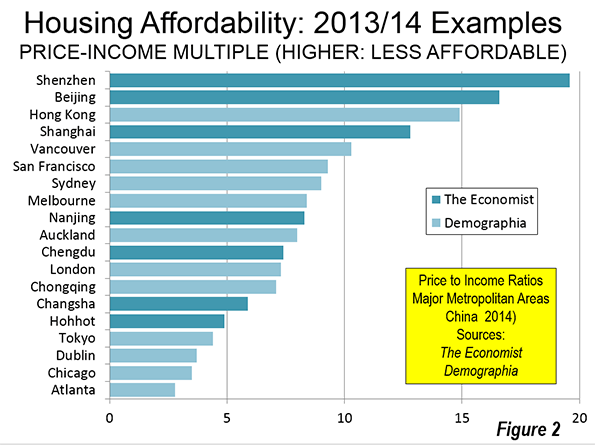

The Bay Area, for all its vaunted progressivism, increasingly resembles a “gated community” whose high prices repel most potential newcomers, particularly families. Already by far the nation’s least affordable city—only 14 percent of current residents can possibly afford to buy a home—it represents a growth model that is by definition exclusive, almost a throwback to medieval forms where the rich clustered inside the city gates.

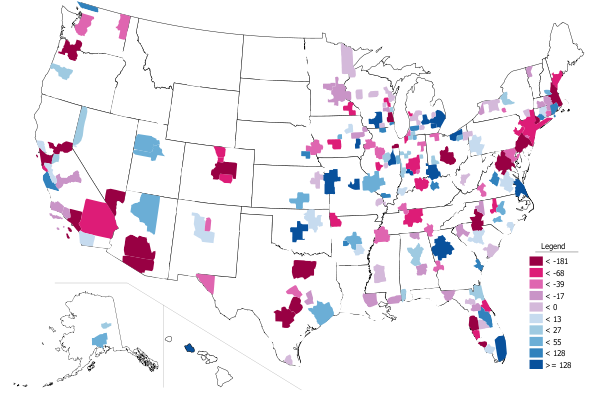

High housing prices, notes economist Jed Kolko, account for the fact that, despite the boom, population growth in the Bay Area remains well below national averages. From 2000 to 2013, the region lost approximately 550,000 million domestic migrants. Despite sizable immigration, the regional population growth rate has fallen below the national average.

In contrast, Houston is among the fastest growing regions in the country, with rapid increases both in domestic migrants and newcomers from abroad. This stems from both lower housing prices and a growth model that is far more amenable to higher paid blue collar and middle management positions. Since 2000, Houston’s population has grown by 30 percent compared, three times that of the Bay Area.

Ironically, Houston’s growth has been more egalitarian than that of the notionally super-progressive San Francisco region. A recent Brookings report found that income inequality has increased most rapidly in what is probably the most left-leaning big city in America, where the wages of the poorest 20 percent of all households have actually declined amid the dot com billions.

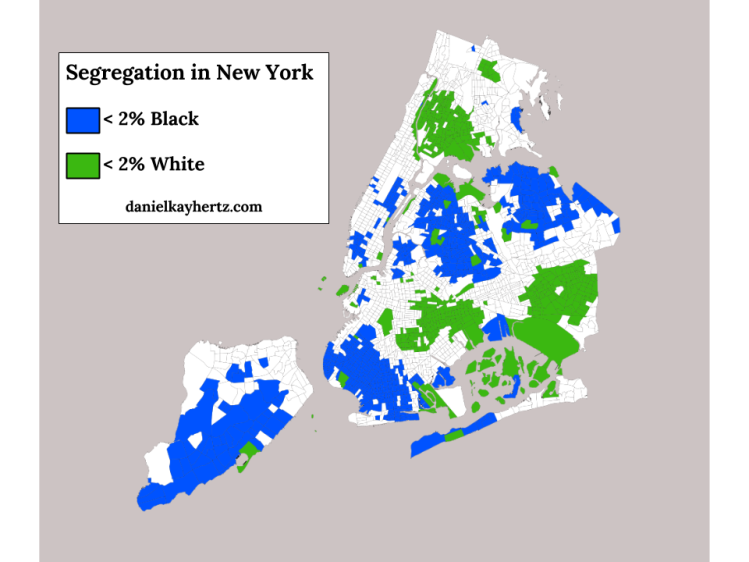

This inequality has a distinct racial element. The Bay Area gap between white residents (who dominate the tech economy) and minorities is among the highest in the nation while, during the boom, income has fallen for Hispanics and African-Americans, according to Joint Venture Silicon Valley.

This racial divergence is far less pronounced in Houston, while the growth of poverty since 2000 has been slower, increasing at one third the rate of New York and San Francisco, and half that of Los Angeles. The Texas city may lack the great views of San Francisco, but Houston has turned out to be a better city for middle class minorities. Homeownership among African Americans stands at 42 percent and for Latinos at more than 53 percent; this compares to 32 and 37 percent in the Bay Area.

Perhaps the biggest differences can be seen in families. Of the nation’s 52 largest metropolitan areas, the Bay Area has the lowest percentage, 11.5 percent, of people ages 5 to 14. In Houston, 23 percent of the population fits this age category. In particular San Francisco is notoriously inhospitable to families, with the lowest percentage of kids of any major city.

The two regions also reflect very different urban forms. The Bay Area’s leadership has opted to favor dense “in fill” growth and sought to restrict suburbandevelopment. Houston has taken a different tack. As its population has expanded, so too has the metropolitan area. This includes the development of many planned communities that appeal to middle class families and many immigrants. In 2013, Houston alone had more housing starts than the entire state of California.

But it would be wrong to dismiss Houston’s model as merely “sprawl.” Instead it is better seen as simply expansive. In fact, arguably no inner ring in the country has seen more rapid growth, with high-rise, mid-rise and townhouse development in many long neglected districts. The increase in high-density housing tracts (more than 5,000 per square mile) since 2000 has been almost ten times higher than the Bay Area.

The Political Battle for the Future

Increasingly America’s future will be determined by these two cities, with the issue of addressing climate change at the fore. Much of the Bay Area’s leadership—led by the likes of Google Chairman Eric Schmidt and investor Tom Steyer—have all but declared war on the oil and gas industry. Several colleges and universities in the region, including Stanford, have shed their energy holdings, and Silicon Valley has nurtured movements such as Bill McKibben’s 350.org that seek to revoke the “social license” of big oil, a tactic used previously against the tobacco companies and firms that did business in apartheid South Africa.

The elites of Silicon Valley and San Francisco are not just interested in saving the earth; they wish to profit from a change in the nation’s energy economy. Google, Sun Microsystems founder Vinod Khosla, and top venture capitalists such as John Doerr have bolstered their already ultra-thick wallets by capitalizing on “green energy” subsidies and outright grants from various levels of government. Given these investments, it’s easier to understand the Valley’s support for draconian climate change legislation, complete with attempts to demonize “Texas oil.” (One won’t see such populist zeal on , say, increasing capital gains rates.)

The Valley’s hostility to fossil fuel energy, and its jihad to destroy an entire industry, is only barely recognized in Houston. I also have never heard anyone there suggest that Silicon Valley should be closed down as a danger to the planet (or at least a threat to the attention span of younger Americans). Houstonians, particularly in the energy industry, generally lack media savvy, which is one reason why energy is widely rated as the country’s least popular industry. Also missing, thankfully, is the sense of entitlement and self-congratulation one finds in the Bay Area. But once the intention to devastate the oil and gas industry is better understood, expect the energy capital to square off against the tech center, generating what may be the regional battle royal of our era.

This piece originally appeared at The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Photos courtesy of University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Office of Communications and Vincent Bloch.

![]()