Maybe it's my age, but, somehow, the future does not seem to be turning out the way I once imagined. It's not just the absence of flying cars, but also the lack of significant progress in big things, like toward space colonization, or smaller ones, like the speed for most air travel or the persistence of poverty.

Indeed, despite the incessant media obsession with technology as the driver of society, it seems we are a long way from the kind of dramatic change that, say, my parents' generation experienced. Born at the end of the horse-and-buggy age, they witnessed amazing changes – from the development of nuclear power and the jet engine to the first moon landing.

In contrast, my children's experience with technological change is largely incremental – a shifting of digital platforms, from desktops to laptops to tablets and iPhones. The new raft of minidevices are ingenious and much more powerful than even the high-end desktop computers of a decade ago. But this wave of technology is not doing much except, perhaps, to make us ever more distracted, disconnected and obsessed with trivia.

As one former Facebook employee put it succinctly: “The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads. That sucks.”

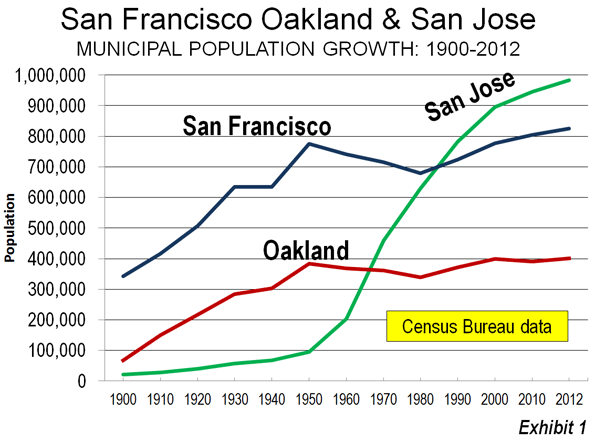

One clear sign of our technological fail: the stagnant, or even declining, living standards for most Americans. New technology is not creating much-cheaper and better housing, nor is it reducing poverty or creating a new wave of opportunity for grass-roots businesses. In fact, the current “tech boom” has done little to improve incomes much outside a few stretches of the Bay Area, a handful of college towns, and overhyped city media districts.

Even Silicon Valley's proud tradition of truly ground-breaking innovation in engineering has slowed as the tech hub has become dominated by media and advertising-driven software companies. The prospect of the easy score in social media, notes longtime entrepreneur Steven Blank, “marks the beginning of the end of the era of venture capital-backed big ideas in science and technology.”

Worse of all, the stagnating tech world is steadily reducing our own dreamscape. Zohar Liebermensch, a student from my “history of the future” class at Chapman University, compared the initial visions of Disneyland's Tomorrowland with later concepts. Over each generation since the park opened in 1955, she found, designers had to ratchet down the more ambitious projections – such as a manned mission to Mars – as the prospects dropped for their actually occurring.

Disneyland, she noted, also cut back on refurbishment in the “Carousel of Progress” exhibit, focused on the future “typical” American family. In the early years of the park, updates were needed every three years. That became six years, then nine. The attraction now hasn't been significantly modified in 18 years. “This increased changeless period,” she notes, “waves another flag of concern, as it demonstrates Disney's view that there has been no noteworthy progress in almost two decades.”

Science fiction testifies most strongly about our technological underachievement. Stanley Kubrick's “2001: A Space Odyssey,” notes author David Graeber, assumed that a 1968 movie audience would find it “perfectly natural” that, by 2001 – now, more than a decade ago – there would be regular commercial flights to the moon, advanced space stations and hyperadvanced computers with human personalities.

Essentially, our new tech doesn't offer anything like the revolutionary and broadly felt changes brought about by electricity, jet travel or, for that matter, indoor plumbing. Meanwhile, the major productivity enhancements spawned by the computer and Internet revolutions, notes Northwestern University economist Robert J. Gordon, have already taken place, while the new social-media technology has done very little for productivity.

This trend has long-term implications for our society and economy. Increasingly, economists, such as Tyler Cowen, suggest that are we seeing a slowing of breakthroughs, with benefits increasingly accruing to a relative handful. We may hope to create a terrestrial “Star Trek” reality, but the society we are creating looks increasingly more like something out of the Middle Ages.

Can this decline in our dreamscape somehow be reversed? First, we need to look at the basic causes for our current narrow-casted view of technology. One is a relative lack of competition. In the 1980s personal computer boom, there were scores of companies competing across a broad array of tech sectors, resulting in a few winners, but a rapid evolution of technology.

Today most of the large new niches – mobile software, Web search, social media – are dominated by a handful of companies. The model has shifted from fierce competition to what might be seen as a series of oligopolies dominated by a handful of sometimes shifting companies, largely controlled by a small but powerful group of investors and entrepreneurs. Job creation, even in the boom, has been much slower than in previous booms as tens of thousands of the people engaged in building the backbone of the information age – telecom, semiconductor and computer product firms– are being replaced by numbers of younger, cheaper and often foreign workers.

At the top of this system stands a remarkably small group whose fortunes depend largely on using the Internet as a vehicle for advertising, often based on gross invasion of privacy. “Tech is something like the new Wall Street,” notes economist Umair Haque, “Mostly white, mostly dudes, getting rich by making stuff of limited social purpose and impact.”

Perhaps the biggest loss here may be psychological, the decline of what historian Frederick Jackson Turner called “the expansive character of American life.” Instead of exploring new frontiers, we now obsess over mobile apps, and our Big Picture has devolved into a procession of “selfies.” If anything, in most critical areas, such as housing and transport, we seem to be looking backward, to the days of small apartments, trolley cars or trains. A crowded, poorer future, not a tech nirvana, beckons.

If it's not prosperity for more people, what is the end game of the new tech model? Much of it is profoundly narcissistic, seeking to replace the physical world with a digital one and making most of humanity superfluous. Inventor Ray Kurzweil, now director of engineering at Google, advocates a path to “transhumanism,” with the ultimate aim of creating a kind of immortality by imprinting our brain patterns as software. This “transhumanist” vision also reflects an almost obsessive concern of the 65-year-old inventor, who takes about 150 vitamin supplements a day in hopes of delaying his own demise.

The potential class implications of Kurzweil's transhumanist agenda are particularly troubling. It is likely that much of the new biological technology for many years, perhaps for decades, will not be easily accessed except by the very rich. Those left behind, Kurzweil believes, will end up as what he dubbed MOSHs – Mostly Original Substrate Humans. “Humans who do not utilize such implants are unable to meaningfully participate in dialogues with those who do,” he writes.

Sun Microsystems co-founder Bill Joy suggests that the focus on human-machine interface will end up with “the elite” having greater control over the masses. And, because human work no longer will be necessary, most of us will become superfluous, a useless burden on the system. “If the elite consists of softhearted liberals,” he suggests, they may play the role of “good shepherds to the rest of the human race.” But, under any circumstances, he predicts, the mass of humanity “will have been reduced to the status of domestic animals.”

Clearly, as a society, we need to start thinking about how technology can serve broader human purposes. This is not an impingement on private enterprise: The Internet, and the microprocessor, were developed largely at taxpayer expense, notably through the Defense Department and NASA. Digital technology should be spurring the creation of new competitive companies, not, as we see now, fostering an American version of the Japanese cartels called keiretsu, where firms like Amazon, Google, Apple and Microsoft use their unfathomable riches to dominate a host of fields, from robotics and space travel to health care, even publishing.

Instead of allowing technology to promote oligopoly, we need to spark competition to speed up innovation that could benefit the majority of people, as opposed to creating a class of fabulously rich superhumans. We also need again to expand our physical frontiers – both in space and, with intelligence, on Earth – so more people can live comfortably, with privacy and maximum freedom of action. Let's make Tomorrowland again a place we would like to have our children inhabit.

This story originally appeared at The Orange County Register.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Creative Commons photo "Engineers" by Flickr user ensign_beedrill