On November 6, eight days after Hurricane Sandy’s surge waters flooded the streets, I started volunteering in the Rockaways, where I stayed for much of the next three weeks.

On that first day, I joined an ad hoc group of volunteers and took a school bus full of supplies donated by my Brooklyn neighbors out to a church on Beach 67th Street. Unloading the bus alongside parishioners at the Battalion Pentecostal church I learned that it was the first shipment they had received for the immediate area since the storm, and that aside from the traffic cops waving cars through and a National Grid trailer parked in the church lot, there was still no official presence in the neighborhood.

The donations we brought were being carried away even before the last of them was off the bus, as word spread through the row houses that lined the block. The mother of a disabled girl carried a box of canned food to her powerless apartment and came back to ask for more. Her fridge and cupboards were already emptied.

The other volunteers and I took the empty bus back to Brooklyn to refill it with more supplies and return later that day. On the drive back, only a mile away from the church, I saw a supermarket parking lot with truckloads of donated material guarded by police and national guardsmen. The people around the church, many of whom lost their cars in the flood, had no way to get the supplies from the parking lot back to their homes, which was incidental since most of them, cut off from any news that didn’t pass by mouth, didn’t even know that the goods were there.

On my second day in the Rockaways I took some time to drive around and see how things were in other neighborhoods, looking for places like the church on 67th Street that were not yet being helped. I found that at the St. Francis de Sales church in Belle Harbor, on 129th Street, some supplies were already being turned away, as boxes had filled the large main hall and were now overflowing into additional rooms to accommodate the constant influx of donations.

Several days later I returned to Francis de Sales to ask that they send food to an apartment complex I had found on the tip of the peninsula near Nassau county, where hundreds of elderly residents were living without heat or power, rationing canned goods and prescription medicine. An Australian volunteer at the church told me that he would take care of it, and while I believed he meant it, I also knew that he might be gone the next day, back to work or to his life outside volunteering.

No one was keeping track.

There is a city agency charged with just that: the Office of Emergency Management (O.E.M.). Emergencies are, by definition, chaotic, and the office is there to do two things: to compile block-by-block information into a unifying big picture, and to ensure responders and resources are allocated in accordance with that picture. In short: triaging, first understanding needs, and then prioritizing among them. But O.E.M. was conspicuously absent while I was in the Rockaways, and according to volunteers and officials I spoke with while reporting this story.

Trying to get people food and basic supplies took up much of my first week in the Rockaways, and yet there was no problem with scarcity. The city spent close to $3 million for food and water distribution and, as of November 26, had distributed over 2 million meals, while donations poured in from New York and out-of-state charities.

Individuals and small groups were doing their best to attend to immediate need, but the lack of direction was acute, resulting in a feast-or-famine situation that varied block by block.

I visited the parking lot where I had seen the trucks of supplies parked and asked if they could be moved to the under-served church on 67th Street but the National Guardsman posted there explained apologetically that taking supplies neighborhood-to-neighborhood, a more effective manner of distribution, didn’t match their orders.

Though city officials had been working hard since even before the storm struck, one thing they weren’t doing was taking control of the situation on the ground, canvassing neighborhoods to determine needs and directing services and supplies accordingly. Nor, since they may not have enough staff to do this all themselves, were they effectively organizing and commanding the hodge-podge of official and unofficial groups and the steady stream of volunteers attempting to make themselves useful.

Relief supplies managed by the city were being delivered to a handful of centralized points without much of a plan for getting them to the people in need, even as the National Guard and the many volunteers looked for ways to help.

Some volunteer groups had identified this issue early on and attempted to deal with it, on their own, in various ways.

Some drove around with supplies until they found people who obviously needed them, and some groups like Occupy Sandy and Save the Rockaways used social media and web presence to post alerts identifying where food and volunteers were needed.

Team Rubicon, a veteran-led relief group, took things even further, using a computer program called Palantir to create an annotated map of conditions in the Rockaways and by stepping up to fill the leadership vacuum. Palantir is a data visualization platform used by the military and intelligence agencies to track and analyze the information gathered from complex environments. It can be highly effective but ultimately relies on human users inputting information gathered from the field.

The group was initially collecting handwritten work orders and reports on local conditions from team members and local residents to track what work was ongoing and what remained to be done. The task of gathering intelligence and feeding into a single model, whether by writing on a map or using a digital database, is a basic pre-condition for conducting any complex operation—you need to understand an environment in order to address its problems. Once they had Palantir added to their system, Team Rubicon could take any report and add it to their database to create a single fluid model of conditions on the ground.

When they first arrived in the Rockaways Team Rubicon intended to be a labor force moving supplies and shoveling out flooded basements. But as the crisis dragged on and more volunteers began arriving in the thousands without any government agency directing their work, Rubicon’s leaders shifted their priorities. Rather than doing all the shoveling themselves, they organized the incoming volunteers into small groups with one Rubicon member assigned to each as a team leader, and dispatched the groups to fill the hundreds of work orders that they had compiled through their canvassing.

As effective as Team Rubicon’s approach was, their reach was limited by their size and the fact that they were only one group among many without any official authority to direct overall efforts. Rubicon’s methodology, collecting and centralizing information in order to coordinate actions, could have been used by the city and implemented on a larger scale and in fact is precisely the approach outlined in the city’s own emergency relief protocols. But, over a month after the hurricane hit, the city’s relief effort still lacks the crucial aspect that has been missing from the start—an effective overhead body leading operations.

Information management is not just an issue for the next emergency: inefficiencies and failures are still occurring because different volunteer groups are not forced to share information and none of them, despite their working relationships, are really on the same page as the city. As one official in a volunteer group that worked with the city during relief efforts put it, “The city had the intel arms in place, the volunteer groups out in the neighborhoods, but they had no system to receive our reports.”

When the city finally started to use volunteer groups for canvassing, it appears to have done so only at the urging of those groups, long after the storm hit.

A Times article details the city housing authority’s failure to properly account for and provide relief to city residents, many of them elderly and unable to evacuate, stuck for weeks in buildings without power or heat. Almost two weeks after the storm, the city called on volunteer groups to go door to door in public housing in Coney Island, surveying to establish how many thousands were stuck in the buildings and what their immediate needs were.

Responding to complaints from volunteers about the city’s lack of leadership in those relief efforts, Nazli Parvizi, the city’s commissioner for community affairs, is quoted in the Times piece saying that the she didn’t want to disturb the volunteers’ good work by taking control of the situation.

According to Parvizi, “I wasn’t here to change that narrative [of volunteers leading while the city played a supporting role]. I was asking them, ‘What do you need?’”

Give Parvizi credit for being honest and not pretending, as many officials have, that the city was aggressively leading relief operations.

The task of coordinating the efforts of various government agencies, volunteers and non-governmental organizations, and providing an overarching structure for emergency response, is precisely what New York City’s Office of Emergency Management (O.E.M.) was created to do.

On its website O.E.M. lists “on-scene coordination” as one of the core responsibilities it assumes an emergency. Yet it was only seen sporadically in the hardest-hit parts of the city—including the Rockaways, Staten Island and Coney Island—and was entirely absent from the wave of city-official-sourced tick-tocks and other stories.

Founded in 1996 by an executive order from Rudy Giuliani, the office effectively took responsibility for emergency planning and response away from the NYPD and gave it directly to the mayor’s office, reportedly to the displeasure of Howard Safir, who was the police commissioner at the time.

In 2001 after becoming its own independent department outside of the mayor’s office and proving its worth in the eyes of many by its response to the attacks of 9/11, O.E.M. seemed to have justified its founding mission and earned an enduring presence. But things changed when Bloomberg was elected and Ray Kelly returned to take over the NYPD. According to multiple sources and news accounts, Kelly, like Safir before him, saw O.E.M. as an affront to the primacy of the police department’s role in ensuring public safety and pressured the mayor to marginalize the organization.

Apparently he had some success in this regard. In 2005, O.E.M. commissioner Joseph Bruno testified before the City Council in a hearing over Bloomberg’s decision to place responsibility for handling hazardous materials in a potential terrorist incident into the hands of the NYPD.

In his testimony, Bruno stated that his office had been more powerful under Giuliani and that in the event of a dispute between the FDNY and NYPD on the site of an emergency he would “give advice,” but “O.E.M. is not going to come in and say, ‘We’ll tell you how to do it.’”

According to a high-ranking official in a prominent volunteer relief organization who has worked closely with both the mayor’s office and O.E.M., tensions between the offices were obvious during the initial, crucial days following the hurricane and communications terse and perfunctory. This official said that whenever there were disagreements between O.E.M. and the mayor’s office, the mayor’s office won.

O.E.M. declined to provide comment for this story, but conversations with sources with knowledge of O.E.M.’s operations and a review of the organization’s history and the turf wars that have shaped its current role provide some insight into what went wrong, and ideas about why those problems are likely to recur in the next disaster. On paper, OEM had all of the tools and resources in place to address these problems. The Citywide Asset and Logisitics Management System (CALMS), created in 2003, is touted by the office as its means of facilitating the movement of supplies in emergency response, and as a crucial part of their mission to “[work] with government agencies and nonprofit organizations to provide assistance to disaster victims and manage relief efforts, donations, and spontaneous volunteers.” According to the O.E.M. website, “CALMS integrates multiple resource management systems and provides a single view of the resources managed or accessible to response agencies.”

But at a meeting held two weeks ago by the New York City chapter of Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (VOAD), with an O.E.M. liaison in attendance, the system's shortcomings were made clear.

VOAD, which brings together a coalition of volunteer groups to plan and coordinate relief efforts and which has been meeting regularly since before Hurricane Sandy, seems not to have been connected to O.E.M.’s system. The volunteer official that I spoke with attended the VOAD meeting last week and told me that a member of Occupy Sandy stood up to plead for help with ongoing food shortages while across the table a Red Cross official offered that he had a fleet of trucks loaded with food and only needed to know where to send them.

A second official in a volunteer group I spoke to described driving around the Rockaways on the day of the Northeaster that followed Hurricane Sandy, canvassing neighborhoods to find the people most vulnerable to the coming snowfall. Seeing an O.E.M. setup, he stopped to do some coordination and trade notes and found that the O.E.M. officials were packing up to leave the Rockaways and return to Manhattan in anticipation of the storm.

“Here we were, volunteers going into the storm, and they were leaving,” he said. “It was just gross negligence on their part.”

Media coverage of the city’s reaction to the storm mostly reflects the overriding political priority, which is getting as much federal aid money as possible, and figuring out the expected tens of billions in funding once it begins to come in.

Bloomberg, aware that the polls showed a big majority of New Yorkers approved of the administration’s response to the storm, has focused his limited criticism on flaws in preparedness and on the question of whether to build sea walls.

A full accounting of the city’s performance will take time and the disclosure of public records not yet available, but the process can start with some simple questions. What should New Yorkers expect of the city when disasters occur? What agencies are responsible for the unique and critical needs that arise from emergencies? Whose job is it to feed individuals and families stuck in homes without power? What is the role of volunteer organizations in disasters of this kind, and to whom are they accountable?

The core elements of OEM’s mission—on-scene coordination, logistics management, directing government and non-government groups—constitute a short list of the critical functions that have been most lacking in the city’s response. New Yorkers will need real transparency from the office and an accounting of the functioning of city agencies during and after the storm.

As of this writing, the records of O.E.M.’s action since the hurricane are still minimal, and the office has yet to initiate its own after-action review.

This piece first appeared at Capital New York.

Jake Siegel was born and raised in Brooklyn. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, New York Press and New Partisan. HIs short story will appear in "Fire and Forget" an anthology of fiction written by Iraq and Afghanistan veterans being released by Da Capo on February 12, 2013.

Rockaway Beach hurricane response photo by Bigstock.

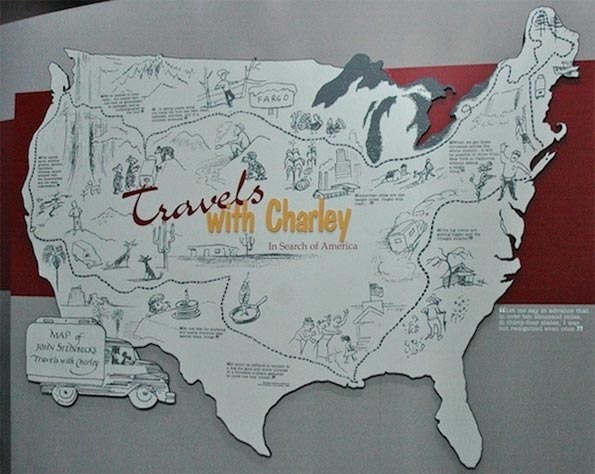

a collection of historical travel essays. His next book is Whistle-Stopping America.

a collection of historical travel essays. His next book is Whistle-Stopping America.